Last updated: September 3, 2025

Article

Do Midwestern National Parks Provide Good Bird Habitat?

NPS/Great Lakes Network

NPS/T. Gostomski

The value of midwestern national parks to breeding birds depends on habitat conditions inside and outside of park boundaries. These influences on birds vary by species, and neither they nor the trends in land cover change have been studied for national park units in the Midwest Region (MWR; also known as Interior Region 3, 4, 5). This despite evidence of ongoing habitat loss exacerbated by human population growth.

We sought to determine if there was a difference in bird species abundance between parks and the areas with similar land cover outside of them. We also wanted to see if we could infer how the habitat available within and around park borders may affect any difference in bird populations.

NPS/Great Lakes Network

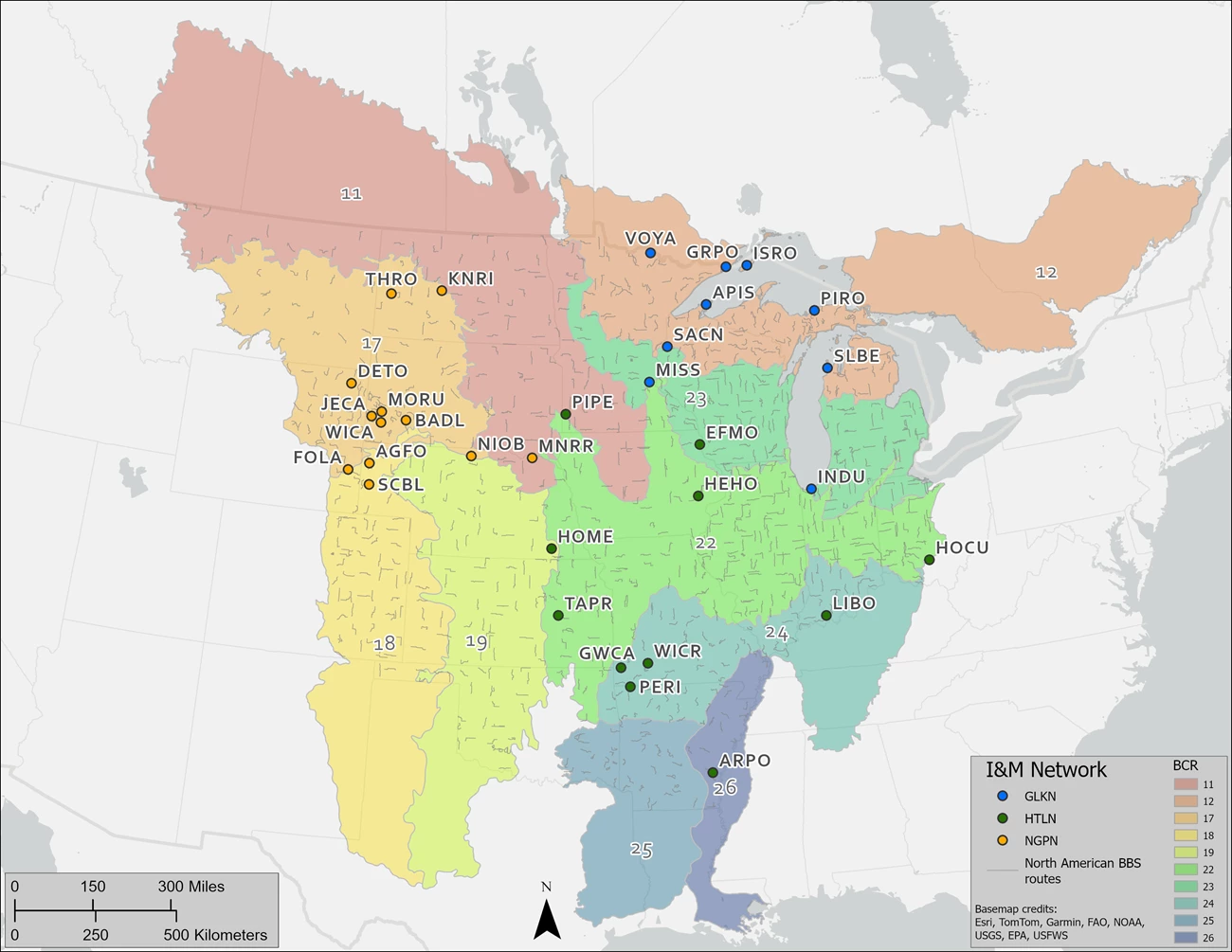

The MWR contains 64 national park units in 13 states. The National Park Service's (NPS) Inventory and Monitoring Division is made up of 32 networks nationwide, three of which are in the MWR. Network scientists conduct long-term monitoring in 37 of the MWR’s 64 national park units: nine parks in the Great Lakes Network (GLKN), 15 parks in the Heartland Network (HTLN), and 13 parks in the Northern Great Plains Network (NGPN). We also identified the Bird Conservation Region (BCR) associated with each park.

What We Did

-

Gathered bird monitoring data collected on North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) routes near each park.

-

Selected a total of 45 bird species of interest based on conservation priority status in each of the BCRs.

-

Analyzed the BBS data to come up with predictions for the presence of each bird species of interest inside each park based on its relative abundance outside the park.

-

Compared our predictions with bird survey data collected in each national park unit to determine if the same bird species were more or less prevalent in parks than expected.

-

Gathered information from the National Land Cover Database (NLCD) and identify land cover types in each park and at distances of 3 and 6 miles (5 and 10 kilometers) around each park boundary.

-

Used broad categories of agriculture, developed, forest, herbaceous, and wetland cover types to analyze change over time.

What We Found

As expected, statistically significant changes in land cover occurred outside the parks more often than inside them across the entire region. Developed land showed the largest number of significant trends followed by agriculture, forest, herbaceous, and wetland classes. The greatest number of landscape changes occurred in the Badlands and Prairies (BCR 17), where most of the Northern Great Plains Network parks are located, and in the Boreal Hardwood Transition (BCR 12), where most Great Lakes Network parks are located. Together, these two BCRs accounted for 48% of the significant landscape changes.

NPS/T. Gostomski

In the Great Lakes Network Parks

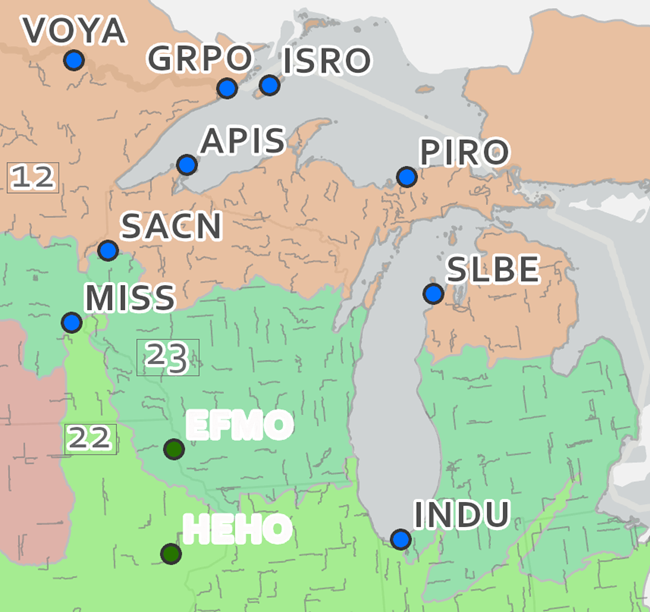

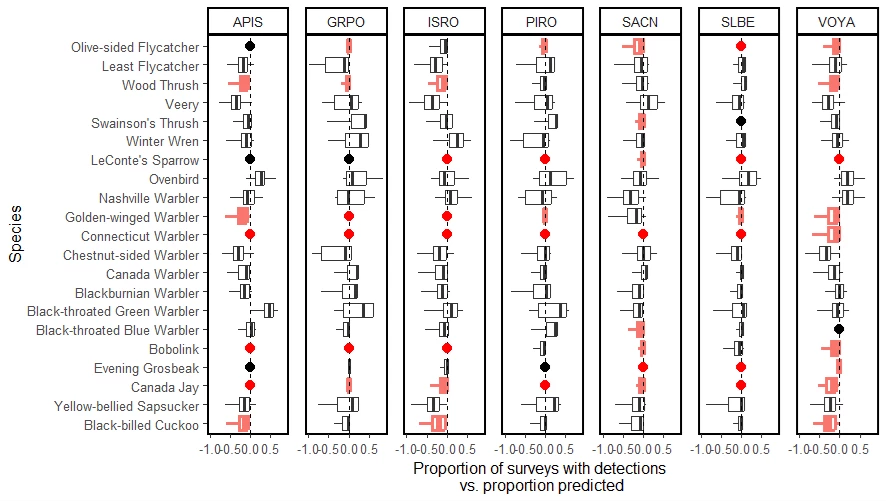

Bird species of interest for BCR 12 were found in the Great Lakes Network parks at comparable rates to the BBS routes outside the parks (Figure 1; APIS=Apostle Islands, GRPO=Grand Portage, ISRO=Isle Royale, PIRO=Pictured Rocks, SACN=north half of St. Croix Riverway, SLBE=Sleeping Bear Dunes, VOYA=Voyageurs). Landscapes around all these parks—and inside some of them—showed significant changes in the agricultural and developed classes, while wetlands increased significantly both inside and outside VOYA.

USGS

USFWS/J. Bonello

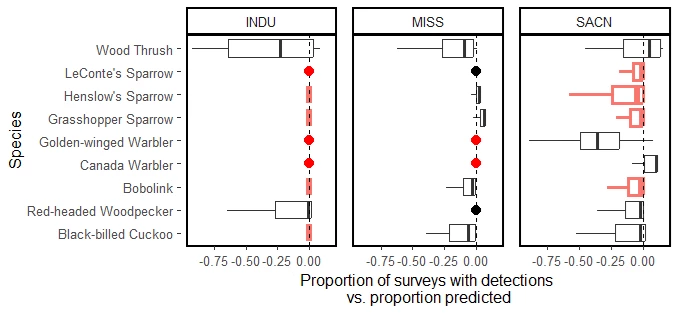

Two GLKN parks—Mississippi River and Indiana Dunes—and the southern half of the St. Croix Riverway are in the Prairie Hardwood Transition (BCR 23). Like the parks in the north, occupancy by bird species of interest in these parks was also comparable to BBS routes outside the park (Figure 2). However, only two of the nine priority species were detected at Indiana Dunes (Wood Thrush and Red-headed Woodpecker). The parks in this BCR lie within a matrix of agricultural, developed, and forest land cover types, and all parks in this BCR experienced significant changes at varying scales in all three cover types.

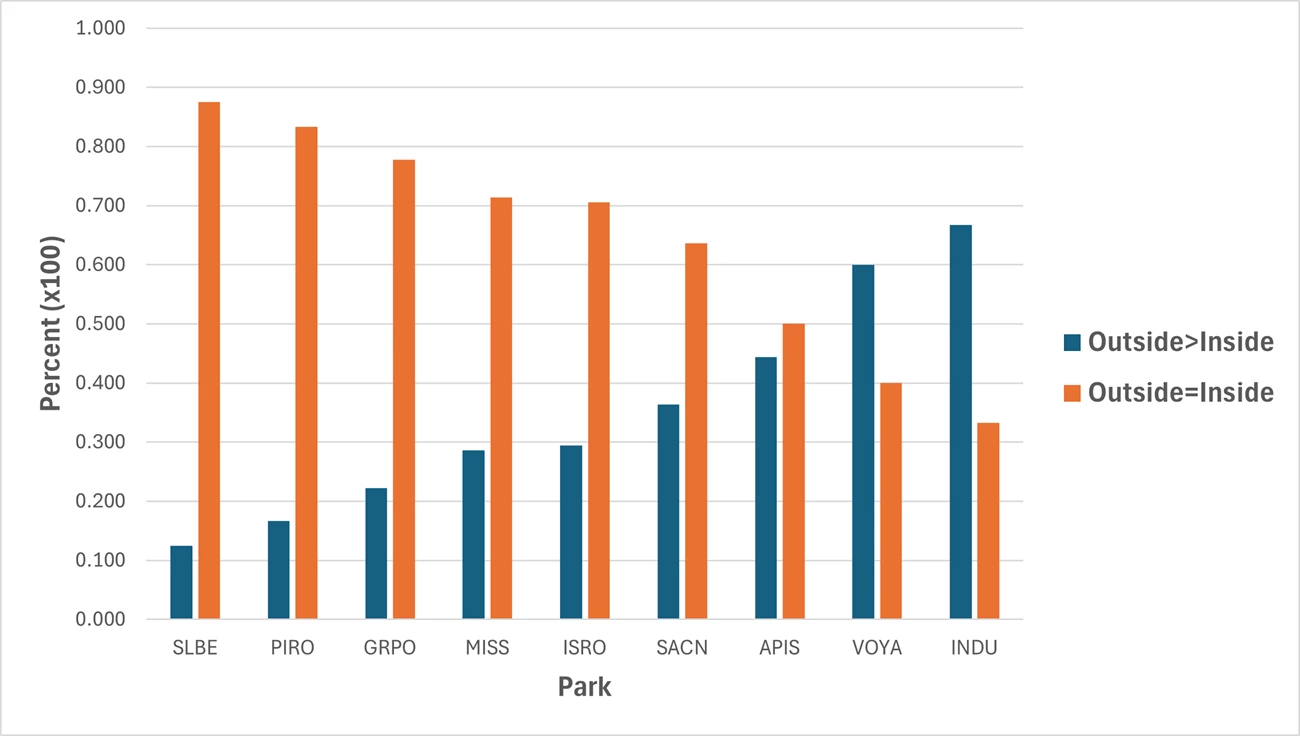

In seven of the nine Great Lakes Network parks, 50% or more of the bird species of concern were detected inside and outside of parks in equal measure (Figure 3). At Indiana Dunes and Voyageurs, 66% and 60% of the species, respectively, were more frequently detected outside the parks than inside. Apostle Islands was the only park with a species of interest (Black-throated Green Warbler) that was detected inside the park at higher rates than outside the park.

USGS

NPS

What’s Around Parks Affects What’s In Them

Birds seem to be faring better in Great Lakes Network parks than in the other MWR networks, where the general tendency was for birds to be detected more frequently outside the parks than inside them. But we must remain vigilant.

A 2011 study of two Great Lakes region national park units found that creating a national park helped to improve habitat within the park by reducing and stopping development, but the creation of more visitor amenities led to enhanced development around both parks. Another study in 2015 found that housing density at the boundary of protected areas tended to have a strong negative influence on abundance and richness of bird species. We saw this in our analysis of land use around INDU and MISS, where development in the parks was less than outside, and forested lands were more common in the parks, but the trends show significantly increasing development in and around the parks and decreasing forested land. Still, a little more than 70% of bird species of concern at MISS occupied habitats inside and outside the park equally (see Figure 3).

The coarse nature of land cover data did not allow us to consider fine-scale habitat requirements. For example, we did not distinguish between coniferous vs. deciduous forest types and we only analyzed total land cover within a given area. Nevertheless, NLCD land cover classes are known to be good predictors of bird species richness and abundance. Perhaps as land cover data continue to improve we can refine our analyses and identify finer details of the relationship between bird populations and habitats in parks.

Burner, R.C., A.A. Kirschbaum, T. Gostomski, and D.G. Peitz. 2025. US national park units as breeding bird habitat: A comparison of species prevalence and land cover across the midwestern and central United States. Science Report NPS/SR—2025/317. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado (https://doi.org/10.36967/2312602).

Tags

- apostle islands national lakeshore

- grand portage national monument

- indiana dunes national park

- isle royale national park

- mississippi national river & recreation area

- pictured rocks national lakeshore

- saint croix national scenic riverway

- sleeping bear dunes national lakeshore

- voyageurs national park

- great lakes network

- glkn

- inventory and monitoring division

- monitoring

- landbird monitoring

- landscape dynamics

- land cover and use

- songbirds

- midwest region

- landbirds

- sleeping bear dunes national lakeshore