Last updated: July 28, 2025

Article

Divided Loyalties

NPS

“My husband and I had some discussion in regard to the merits of the war at the beginning. He was a Virginian and perhaps his sympathies were more for Virginia than for the North, but he never voted for the ordinance of secession. I was not a Virginian and opposed to secession.”

—Caroline Heater

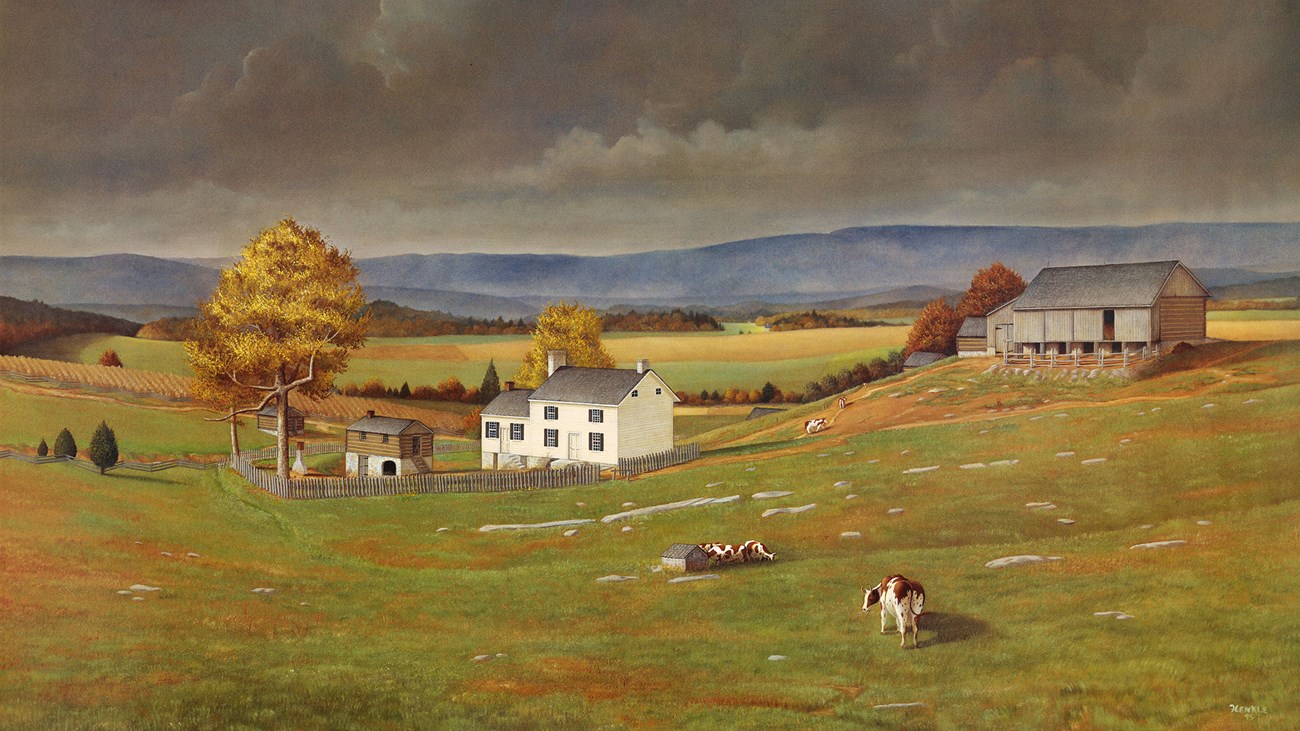

Solomon and Caroline Heater bought this farm, whose fields you see here, in 1843. Their hard work turned it into a prosperous 540-acre farm producing wheat, corn, and dairy products. Solomon Heater was from Loudoun County, Virginia, and supported his native state. Caroline was born and raised in Pennsylvania and supported the Union. John Heater, their oldest son, fought for the Confederacy, and died of wounds in January 1864. A second son, Henry, died in a Union prison, in March 1865. A third son, Charles, was 8 years old in 1861 and survived the war. The farm suffered damage throughout the war: both sides took food for the men and horses, fences became firewood, and farm implements disappeared. The fighting on October 19, 1864, caused further destruction.

The Heater Family, Slavery, & Secession

Caroline Heater was from Pennsylvania and was "violently opposed to slavery." Her husband was from Loudoun County, Virginia, but the couple brought no slaves to their farm and never used slave labor. They and their three sons prospered and nearly doubled the original 274-acre farm to 540 acres. The Heaters added a large German bank barn behind the house, a smokehouse, stables, another granary, and a still.

Like most families in the Shenandoah Valley, the Heater's relatively small family farm produced wheat, corn, apples, and goods from a modest herd of dairy cows. Unlike the next-door Belle Grove with its thousands of acres, or the large, labor intensive cotton plantations in eastern Virginia, the Heater farm had no need for slave labor.

When the slavery debate reached a boiling point in 1860, the residents of the Shenandoah Valley were split on the question of secession. The valley had far fewer slave owners than the rest of the state on the other side of the Blue Ridge, but its residents were mostly Virginians, after all, and more loyal to their state than the country.

The Heater family felt the divide just as many of their neighbors did. Solomon was a Virginian and sided with his native state. Having emigrated from Pennsylvania, Caroline had no such loyalty. She was nervous about the coming war and the destruction it was sure to bring. She later remarked,

"We shall have graveyards at every door. My husband and I had some discussion in regard to the merits of the war at the beginning. He was a Virginian and perhaps his sympathies were more for Virginia than for the North, but he never voted for the ordinance of secession. I was not a Virginian and opposed to secession."

When the first convention to discuss secession was held in Richmond in the spring of 1861, 19 delegates from the Shenandoah Valley went to represent its citizens. After the first call and vote to secede, only 4 out of the 19 voted in favor, and a majority of all the delegates decided to stay with the Union. It was not until after the firing on Ft. Sumter that the delegates changed their minds. Still, only seven out of the 19 Shenandoah Valley delegates voted to secede. Perhaps they knew that as Virginia's breadbasket and direct route to Washington, D.C., the Valley was doomed to suffer greatly at the hands of both the Confederate and Union troops.

Heater Soldier Sons

Against her wishes, Caroline's two sons fought for the Confederacy. Her eldest, John, was 23 when the war began and had already belonged to a local militia company. He enlisted in the 7th Virginia Cavalry and served under Turner Ashby during Stonewall Jackson's 1862 Shenandoah Valley Campaign. He later fought under Thomas Rosser in the "Laurel Brigade".

John was wounded during a scouting mission in January 1864 near Patterson's Creek, West Virginia. He died of his wounds on January 5th, 1864. Caroline sadly noted, "He has acted contrary to my judgment and my feelings and sympathies in this matter, but I cannot control him, he is of age and has a right to do as he please."

John's younger brother Henry was 17 when the war broke out and was attending school in Front Royal. Along with many of his classmates, he quickly joined a military company known as the Warren Rifles. The group eventually became part of the 17th Virginia Infantry. Henry wrote home, asking his mother for a uniform, which she declined to produce. "Henry thought it was all fun and did not know the hardships he would have to undergo … and did not get any military equipment's [sic] or anything from me and I never paid for anything he got," Caroline later said.

Henry eventually joined his brother in the 7th Virginia Cavalry. He was captured in August of 1864 and sent to Ft. Delaware prison, where he died on March 18th, 1865. The Heater brothers are buried in Mt. Hebron Cemetery in Winchester.

War at Home

It was not just the Heater sons who experienced war firsthand. Armies from both sides marched through the Shenandoah Valley almost constantly, seeking food, supplies, firewood, and anything else they needed to survive. Caroline and Solomon Heater opened their doors to countless Union troops. One citizen of Middletown recalled, "She entertained not only the officers, but many of the privates and fed them from her own table to the very best of her ability."

On the morning of October 19th, 1864, the Heater family witnessed first-hand the climax of the Civil War in the Shenandoah Valley. Shortly after 7 a.m., the fighting reached the Heater House. Gen. Early used the grounds around the house as a platform to roll out all his artillery to shoot at a remnant of Sheridan's army stationed on a hill above the farm. By the time the smoke cleared, any Union soldiers still alive had fled. That afternoon, after Gen. Sheridan returned to Middletown and rallied his nearly defeated troops, it was Confederate soldiers who fled past the Heater House on their way to Strasburg.

Nothing Left but Ruins

The Heater Farm, like most of those in the Valley, was left in ruins. Caroline Heater had allowed Union troops the use of her home, but they did not treat the property kindly. Soldiers took oats for their horses, food for themselves, fences for firewood, and livestock for subsequent meals while on the march. Farm implements, horses, wagons, cows, and hogs were all gone.

Hoping to be compensated for their loss, the Heaters applied to the Southern Claims Commission in 1871 for restitution in the amount of $12,993. The commission was formed to aid Union loyalists whose property was taken by Union troops. Local citizens attested to Caroline's allegiance. One resident testified,

"We were all straight up and down before the war, but when the war commenced some went one way some the other. Mrs. Heater and myself [sic] would talk very freely on the subject. She always avowed to me her preference to the Union."

Caroline's youngest son, Charles, was eight years old when the war broke out and remained at home. He recalled, "My mother said she wished she had her way with the hotheaded fanatics of the south and she was violently opposed to Jefferson Davis."

Despite these affidavits, the government did not pay any restitution before both Solomon and Caroline died (he in 1872 and she in 1892). They are buried in the Lutheran Cemetery in Woodstock, Virginia. As the only surviving son, Charles inherited the Heater Farm. In 1901 he was finally reimbursed by the federal government in the amount of $5,480, less than half of what the family requested to cover its losses.