Last updated: July 28, 2025

Article

Discovery of Union Hospital Burial in Fredericksburg

History Hidden for 153 years

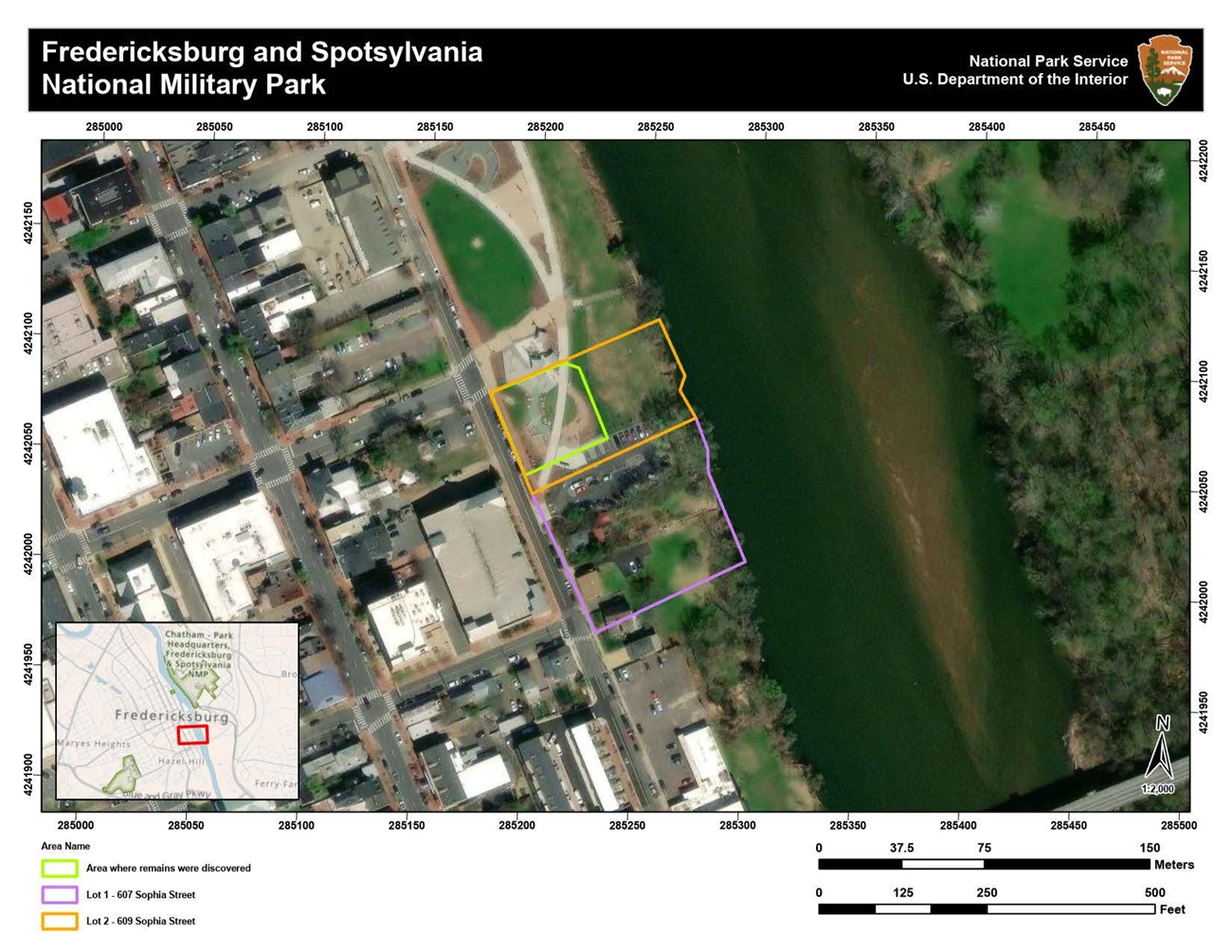

In 2015 human remains were inadvertently discovered by City of Fredericksburg staff during construction for what is now Riverfront Park located on Sophia Street in downtown Fredericksburg, Virginia. This site extended across what was known historically as Lots 1 and 2 from the original plan of the town of Fredericksburg, dating to 1721 (Figure 1). After the remains were determined to be archeological, formal archeological excavations began in the northwestern portion of Lot 2. Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, now a Mead & Hunt Company, was immediately contacted to conduct a salvage operation at the request of the City of Fredericksburg.

NPS Image

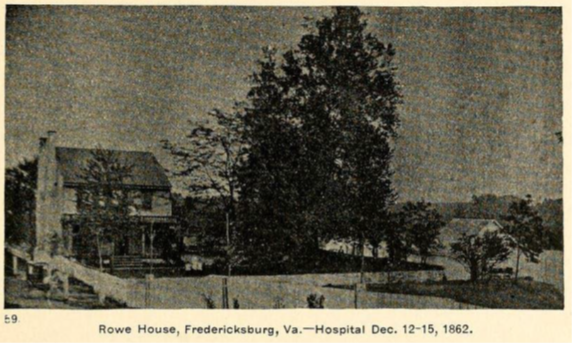

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Lots 1 and 2 were owned and occupied by Absalom P. Rowe (Figure 2). He served as Quartermaster for the Confederate States Army for the duration of the Civil War and after he played a significant role in restoring order to the area. In 1888 he became Mayor of Fredericksburg (Goolrick 1922:113). With the exception of one term, he held the position until his death in 1900 (Goolrick 1922:113).

When Fredericksburg became a battleground and subsequent encampment for thousands of soldiers during the winter of 1862 to 1863, several houses on Sophia Street were occupied by the Union Army. The 14th Regiment Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, among others of the 3rd Division of the Union Army’s Second Corps, used the Rowe House, outbuildings, and grounds as a divisional hospital for their wounded soldiers. This was confirmed in Charles Lyman’s memoir from 1906. Lyman was a second lieutenant in the Fourteenth Connecticut Regiment and described the area:

When Fredericksburg became a battleground and subsequent encampment for thousands of soldiers during the winter of 1862 to 1863, several houses on Sophia Street were occupied by the Union Army. The 14th Regiment Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, among others of the 3rd Division of the Union Army’s Second Corps, used the Rowe House, outbuildings, and grounds as a divisional hospital for their wounded soldiers. This was confirmed in Charles Lyman’s memoir from 1906. Lyman was a second lieutenant in the Fourteenth Connecticut Regiment and described the area:

The next night I was detailed for service at our Division hospital, which had been established at a house on the street nearest the river, with large grounds about it, and several very large trees in the grounds back of and at the side of the house. The wounded officers were mostly cared for in the house, and the noncommissioned officers and privates in the grounds outside… Well towards midnight a man was put upon the rude operating table under a big buttonball tree in the yard, back of the house, for an amputation of the leg above the knee and I called to assist. My function was to sit on a cracker box opposite the surgeon with a candle in each hand, and by the light of these two candles the amputation was made. As it was the first amputation I had witnessed it was to me intensely interesting and what I remember about it especially was the manner in which the surgeon handled the knife and the saw, and that it was a “flap” operation (Page 1906:93–96).

Excavation and Study

The primary focus of the salvage excavation was to examine the location where the remains were initially discovered. However additional areas were also investigated to provide archeologists with a full picture of the Civil War-era landscape in this location. The remains were discovered in what archeologists call a ‘feature,’ which means an area that was excavated in the past and later filled in with cultural materials and surrounding soils.The feature appeared to be a secondary deposit of human remains and associated artifacts. Based on the deposition of the soils, the incomplete nature of the remains, and that none showed evidence of being surgically removed (common in a limb pit), archeologists believe that this feature was the original resting location of three Union soldiers that were then exhumed shortly after the war ended. After the war, the remains of the dead were often exhumed to be moved to a permanent burial location, such as the Fredericksburg National Cemetery or in some rare cases to their homes or home communities. Those responsible for this arduous task would often gather the most prominent specimens like skull and long bones, leaving the smaller remains behind. The assemblage of human remains was primarily composed of bones from fingers and toes of three Union Soldiers (Hatch et al. 2016).

The burial deposit also included a bundle of textiles and artifacts, measuring 5 in. by 4 in. (Figure 4). This bundle of materials is believed to represent the former uniforms of the deceased soldiers as it contained the remains of a Union coat(s) and pants as well as the objects that were in the pockets of the clothing items.

City of Fredericksburg

City of Fredericksburg

City of Fredericksburg

The x-ray revealed a total of 113 artifacts in the small bundle. These materials included eagle buttons, a small patent medicine bottle, straight pins, a pocket watch key, a small horsehair brush, and a cuff-size Connecticut button (Figure 7–Figure 8). The identification of the Connecticut button was especially significant because the 14th Connecticut was the only Connecticut unit in the 3rd Division at the Battle of Fredericksburg, providing additional information as to the potential troops who occupied the site.

City of Fredericksburg

City of Fredericksburg

City of Fredericksburg

After discovery of the remains in 2015, the City of Fredericksburg, the National Park Service (NPS), and the Virginia Department of Historic Resources collaborated to coordinate respectful reburial of the remains in Fredericksburg National Cemetery. Because the remains were found on City property, certain procedural requirements had to be met before reburial in the cemetery could occur.

Once the NPS and the City of Fredericksburg reached an agreement, an archeological excavation of the proposed reburial location was conducted. It was necessary to ensure that no unknown archeological deposits or unknown burials were located in the chosen burial plot. In 2021 archeologists from the Northeastern Regional Archeological Program (NARP), an office of the NPS that supports parks with their cultural resource needs, conducted a ground penetrating radar study followed by archeological testing. This study resulted in the identification of mid-to late 19th century resources associated with the early development and construction of the cemetery. As a result, the park decided not to pursue the establishment of a new burial plot at that location. In 2023 archeologists from NARP conducted excavations at a new location, and no archeological deposits were encountered during this study.

With an area cleared for reburial, the City of Fredericksburg and the NPS moved forward with the reburial plan. With the assistance of the Sons of Union Veterans and Missing in America Project, a reburial ceremony took place in the Fredericksburg National Cemetery on May 2, 2025.

Once the NPS and the City of Fredericksburg reached an agreement, an archeological excavation of the proposed reburial location was conducted. It was necessary to ensure that no unknown archeological deposits or unknown burials were located in the chosen burial plot. In 2021 archeologists from the Northeastern Regional Archeological Program (NARP), an office of the NPS that supports parks with their cultural resource needs, conducted a ground penetrating radar study followed by archeological testing. This study resulted in the identification of mid-to late 19th century resources associated with the early development and construction of the cemetery. As a result, the park decided not to pursue the establishment of a new burial plot at that location. In 2023 archeologists from NARP conducted excavations at a new location, and no archeological deposits were encountered during this study.

With an area cleared for reburial, the City of Fredericksburg and the NPS moved forward with the reburial plan. With the assistance of the Sons of Union Veterans and Missing in America Project, a reburial ceremony took place in the Fredericksburg National Cemetery on May 2, 2025.

References:

González, Kerry S. and Michelle Salvato

2019 Pictures Speak for Themselves: Case Studies Proving the Significance and Affordability of X-ray for Archaeological Collections. In New Life for Archaeological Collections, edited by Rebecca Allen and Ben Ford. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

Goolrick, John T.

1922 Historic Fredericksburg: The Story of an Old Town. Whittet & Shepperson Press, Richmond.

Hatch, D. Brad, Kerry S. González, Emily Anderson, Kerri S. Barile, and Joseph R. Blondino

2016 Archival Research and Archaeological Fieldwork at the Prince Hall Lodge Site (44SP0069-0001), Fredericksburg, Virginia. Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, Fredericksburg, Virginia.

O'Sullivan, Timothy H.

1863 Fredericksburg, Va. View of town from east bank of the Rappahannock. Fredericksburg United States Virginia, 1863. Accessed April 2025, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018666272/.

Page, Charles D.

1906 History of the 14th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry. The Horton Printing Company, Meriden, Connecticut.

Repaska, Mishka and Ruth Armitage

2015 Chemical Characterization of a Civil War Bottle Residue. Department of Chemistry, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, Michigan. Poster presented at department meeting.

Stevens, Henry S.

1893 Souvenir of Excursion to Battlefields by the Soceity of the Fourteenth Connecticut Regiment and Reunion at Antietam, September 1891; with History and Reminiscences of Battles and Campaignes of the Regiment on the Fields Revisited. Gibson Bros., Printers and Bookbinder, Washington, D.C.

González, Kerry S. and Michelle Salvato

2019 Pictures Speak for Themselves: Case Studies Proving the Significance and Affordability of X-ray for Archaeological Collections. In New Life for Archaeological Collections, edited by Rebecca Allen and Ben Ford. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

Goolrick, John T.

1922 Historic Fredericksburg: The Story of an Old Town. Whittet & Shepperson Press, Richmond.

Hatch, D. Brad, Kerry S. González, Emily Anderson, Kerri S. Barile, and Joseph R. Blondino

2016 Archival Research and Archaeological Fieldwork at the Prince Hall Lodge Site (44SP0069-0001), Fredericksburg, Virginia. Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, Fredericksburg, Virginia.

O'Sullivan, Timothy H.

1863 Fredericksburg, Va. View of town from east bank of the Rappahannock. Fredericksburg United States Virginia, 1863. Accessed April 2025, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018666272/.

Page, Charles D.

1906 History of the 14th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry. The Horton Printing Company, Meriden, Connecticut.

Repaska, Mishka and Ruth Armitage

2015 Chemical Characterization of a Civil War Bottle Residue. Department of Chemistry, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, Michigan. Poster presented at department meeting.

Stevens, Henry S.

1893 Souvenir of Excursion to Battlefields by the Soceity of the Fourteenth Connecticut Regiment and Reunion at Antietam, September 1891; with History and Reminiscences of Battles and Campaignes of the Regiment on the Fields Revisited. Gibson Bros., Printers and Bookbinder, Washington, D.C.