Last updated: January 3, 2022

Article

Directors of the American Field Hospital at St. Paul's during the Revolutionary War

Directors of the American Field Hospital at St. Paul’s during the Revolutionary War

For many years, historians were aware of the use of St. Paul’s Church as a Revolutionary War military field hospital -- by the other side. While fighting local battles, both the British army and their hired German allies the Hessians occupied the large, empty, unlocked stone and brick building, transforming it into a makeshift hospital to treat wounded and sick soldiers.

But recent research has confirmed that the Americans, the Patriots, also took advantage of the size, location and facilities of the church building for medical use. We don’t have information on particular soldiers who were treated and probably died in the building. But there is information on two of the doctors who directed the operations. They are two of the Continental army’s leading physicians, Dr. John Morgan and Dr. John Warren, whose careers took remarkably different turns after their tenures at the church hospital.

It was early September 1776, and Washington’s troops had been routed in the Battle of Brooklyn, forced to withdraw across the East River to Manhattan Island. Along with 9,000 troops, draft animals and support equipment, the Patriots removed medical stations. With an understanding that the Revolutionary War was moving north, and that the Patriots might have to evacuate Manhattan, they came to St. Paul’s, or the church at Eastchester as it was called then, based on information supplied to the American army by New York political leaders familiar with Westchester County, part of the same movement of army supplies to White Plains.

The first director of the American hospital at St. Paul’s was Dr. John Warren, younger brother of the famed Revolutionary leader Dr. Joseph Warren. John was a Harvard graduate who had studied medicine with his brother, but, lacking his sibling’s confrontational zeal, was reluctant to embrace the Patriot movement; it seems the death of his older brother at the Battle of Bunker Hill, in June 1775 may have motivated him to embrace the cause. Once enlisted, given his credentials in a medical corps sorely lacking in well trained doctors, John Warren was appointed to important posts, including directing military hospitals in the New York campaign of 1776. A dedicated physician, he worked exhaustively and within a few weeks of assuming his post at St. Paul’s contracted illness, probably small pox, which confined him to a private home in Rye for convalescence.

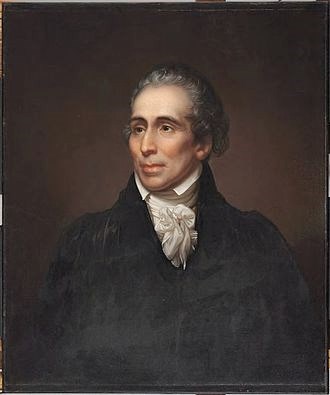

Dr. John Morgan assumed control of a series of Westchester county American field hospitals, including St. Paul’s, and wrote to Warren on October 4 that he was “improving the church at East Chester into an hospital.” Son of a Welsh merchant, Morgan was born in Philadelphia in 1735. Orphaned at 13, he secured livelihood as an apprentice to a physician and later earned a living as an apothecary at the Pennsylvania Hospital. He gathered important experience with military medicine while serving as a surgeon with Pennsylvania troops during the French and Indian War. Far better trained than most colonial doctors, Morgan studied with prominent physicians in London and completed his medical degree at the University of Edinburgh; he was elected to several prestigious European medical societies. Returning to America, he played a leading role in the establishment of a medical school at the College of Philadelphia, which became the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. John Morgan

While he was not an enthusiastic supporter of the Patriot cause -- perhaps because of his close ties to the English medical establishment -- Morgan’s superior training and background led to his appointment as Director-General of hospitals for the Continental army in October 1775. Faced with critical shortages of resources and trained personnel on his staff, Dr. Morgan was already struggling under a torrent of criticism at the time of his tenure at the St. Paul’s church hospital in September/October 1776. Perhaps unfairly, he was held responsible for the high rate of deaths in American military hospitals.

Diplomacy, co-operation and tact were required of such a director while interacting with political and military officials, qualities in which Dr. Morgan was lacking. An acrimonious and vain streak which had caused problems earlier in his career proved especially disadvantageous at this time, and he became embroiled in disputes with the Continental Congress and other army doctors, which led to his dismissal in 1777. Inquiries into his conduct led to Dr. Morgan’s vindication two years later, but he never really recovered. Further shattered by his wife’s post war death, Morgan retreated into an impoverished, reclusive existence, and died in 1789.

Dr. Warren, on the other hand, served commendably through the war, recovering from the illness in 1776 and directing other military hospitals. At the return of peace, he established a successful medical practice in Boston, specializing in surgery, and was selected President of the Massachusetts Medical Society. Dr. Warren performed one of the first abdominal operations in the country. His wellattended lectures on anatomy broadened his reputation within the Boston medical profession and among students at Harvard University. These discourses led to his selection as first faculty member and founder of a new medical school at Harvard, a position he held for 30 years, before passing in 1815.