Last updated: December 22, 2023

Article

Did Ulysses S. Grant Pawn His Watch to Purchase Christmas Gifts for His Children?

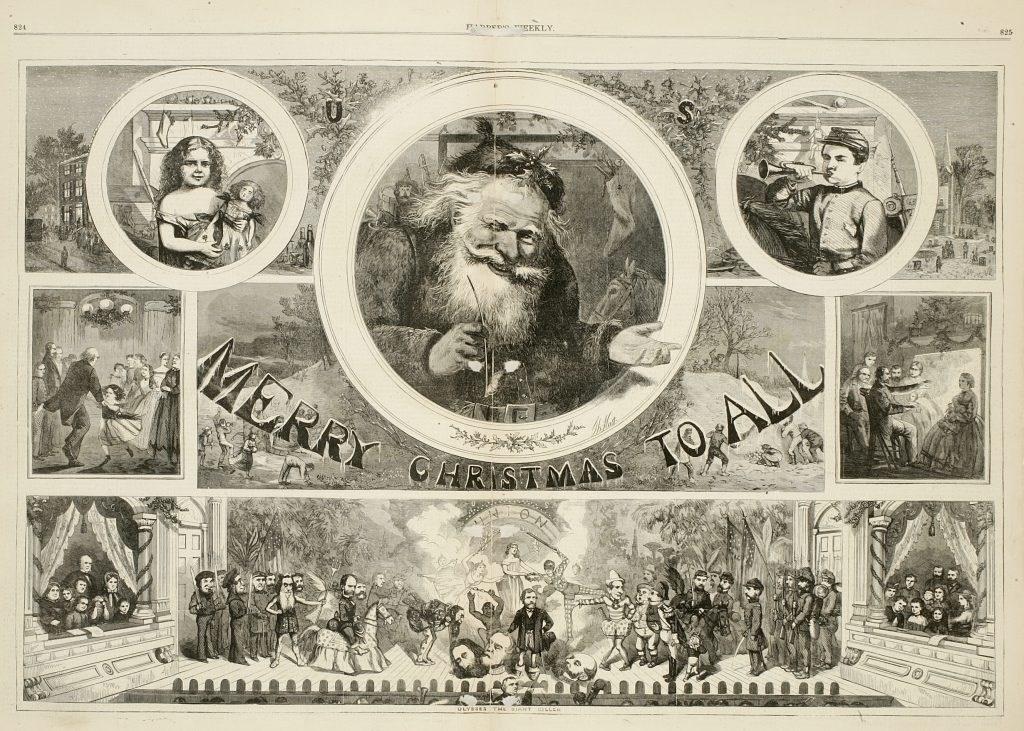

Harper's Weekly

Ulysses S. Grant struggled financially during his time as a St. Louis farmer at the White Haven estate (1854-1859). He tried his best to grow fruit and vegetable crops, sell firewood, and provide for his growing family. However, the combination of poor weather, a poor economy, and health struggles contributed to Grant’s struggles. An important moment often highlighted by historians was Grant’s decision to pawn a gold watch for cash on December 23, 1857. This episode symbolizes Grant’s experiences as a civilian farmer. Author Ron Chernow argues that this moment was “the symbolic nadir of [Grant’s] life.” However, like many historians before him, Chernow claims that Grant’s motivations for pawning the watch were family-oriented:

“As his life steadily unraveled, he pawned his gold watch and chain for $20 on December 23, 1857, to purchase Christmas presents for his children.” Ron Chernow, Grant, 102.

Did Grant actually use this money to purchase Christmas gifts for his children? The story is more complicated than historians have previously suggested.

Grant did pawn a gold watch and chain to J.S. Freligh in St. Louis. More than fifty years after the transaction took place, Freligh’s nephew offered to sell the transaction receipt to an autograph dealer. “I can attest to its authenticity, as I was present at the transaction,” Louis H. Freligh recalled. “[I] saw [Grant] sign his name to the document. Am now 71½ years old, so as I was then less than 20, can very well remember it. Have refrained over 50 years from offering it for sale, because so many people consider it a disgrace to patronize ‘mine uncle,’ & I did not wish to give offense to the renowned general’s family, by exposing the matter.”

The entire receipt reads as follows:

St. Louis, Dec 23rd 1857

I this day consign to J.S. FRELIGH, at my own risk from loss or damage by thieves or fire, to sell on commission, price not limited, 1 Gold Hunting [Watch] Detached Lever & Gold chain on which said Freligh has advanced Twenty two Dollars. And I hereby fully authorize and empower said Freligh to sell at public or private sale the above mentioned property to pay said advance—if the same is not paid to said Freligh, or these conditions renewed by paying charges, on or before Jan 23/58. U.S. Grant

This documentation does not confirm how Grant spent the money once he pawned his watch, which is about $776 in today’s dollars. (One also notes that Chernow incorrectly listed the total money given to Grant as $20, not $22). While historians have latched onto the idea that the money was used for gifts since Grant received the funds two days before Christmas, he may have used the money for any number of reasons. He could have bought food, clothing, farming tools, or livestock with the money, or he may have needed to pay a tax bill. Using all $22 on Christmas gifts also seems unlikely and uncharacteristic of Grant given how large the sum of money was.

Another consideration is that Christmas was not yet a federal holiday in the United States, nor was it uniformly observed by Christians throughout the country as day of rest and gift giving. Grant’s parents were strict Methodists. While focusing on Southern Methodists specifically, historian Cynthia Lynn Lyerly points out that many Methodists refrained from “worldly habits” such as “drinking liquor, playing cards, racing horses, gambling, attending the theater, and dancing (in both frolics and balls).” Puritans and other conservative evangelicals took a similar approach. One may question whether gift giving at Christmastime was a regular practice within Grant’s family during his youth, or if his family observed the holiday before the Civil War.

Yet another consideration is that gift giving was not common in the 1850s. Handmade gifts were more likely to be given in most cases, especially for a family that was financially struggling like the Grants. When gifts were purchased for children, they most likely came from the mother, not the father. Historian Penne L. Restad also points out that many elite Northerners and Southerners alike associated “Christmas gifts with servants and slaves” rather than between their own families. Restad cites a New York Herald article from 1856 that told readers that it was a custom “for the servants of gentlemen, particularly if they were blacks, to go around among their master’s friends to receive Christmas boxes.” This meant that “genteel families [did] not give or receive presents themselves on that day.”

In 1932, the Illinois Historical Society announced that they had acquired Grant’s pawn shop receipt. Later that year The Walther League Messenger, a Lutheran publication that discussed religious and secular topics, wrote about the acquisition. The paper commented that “this act of desperation came at one of the darkest moments in a disappointed life,” but did not mention Grant using the money for Christmas gifts. The claim may have originated with Llyod Lewis’s popular 1950 book, Captain Sam Grant. There, Lewis claimed that Grant pawned the watch because “his family must have presents on Christmas morning and Julia must have a happy holiday, for she was due to have another baby within a few weeks” (referring to the birth of the Grant family's fourth and last child, Jesse Root Grant II, on February 6, 1858). From there, the story seems to have picked up traction and been repeated by historians ever since.

In the end, there is no definitive evidence to verify that Ulysses S. Grant pawned his gold watch in 1857 to purchase gifts for his children. While he did pawn the watch, how he spent the money once he received it is unknown.

Ironically, President Ulysses S. Grant signed a bill into law in June 1870 establishing Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day as federal holidays.

Further Reading

Cynthia Lynn Lyerly, Methodism and the Southern Mind, 1770-1810. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Restad, Penne L., Christmas in America: A History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

John Y. Simon, ed. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 1: 1837-1861. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967, 339-340.