Last updated: September 4, 2020

Article

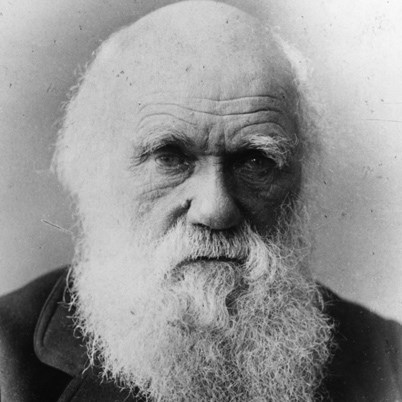

Did Garfield Know Darwin or Twain?

biography.com

On a tour the other day a very bright nine year old asked me, “Did Garfield know Charles Darwin? Did he know Mark Twain?” The question surprised me, but I could answer the first part. Although James Garfield read a great deal by and about Charles Darwin, he never met him. (More about that in another post.) But, did James Garfield ever meet Mark Twain? That I wasn’t sure about; it certainly seemed possible. A little research was required.

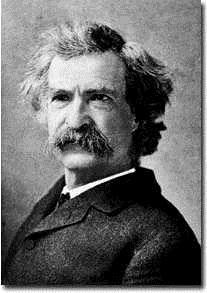

I went to the usual sources, and found in The Life and Letters of James A. Garfield, the family approved biography written by Theodore Clarke Smith, published in 1925, “Twice only does the name of Mark Twain appear in the journal, for the later ‘Twain legend’ was far in the future.”

americanhistory.unomaha.edu

Smith then mentions the journal entry for January 24, 1876, “Read Mark Twain’s article in the Atlantic Monthly entitled ‘A Literary Nightmare,’ a very clever story.” The diary also includes, “May 5, 1878…In the evening the children read from Mark Twain’s Roughing It,” which Smith did not mention, perhaps because it was the children, not Garfield, doing the reading.

mrcapwebpage.com

The index to the published diaries of James A. Garfield led to a couple of additional entries. December 30, 1874, in New York City: “In the evening attended the theater and listened to The Gilded Age, a piece whose stupidity is only equaled by the brilliant acting of Colonel Sellers. The play is full of malignant insinuations and would lead a hearer to believe that there is no virtue in the world, in public or in private life.” The play Garfield saw that evening was based on the novel, The Gilded Age, written by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner in 1873. The title of the book gave name to an era that had certainly inspired Twain’s rapier wit. During the Credit Mobilier scandal, which damaged Garfield’s personal reputation and political standing, Twain had had plenty to say about Congress: “It could probably be shown by facts and figures that there is no distinctly native American criminal class except Congress,” and “I think I can say and say with pride that we have some legislators that command higher prices than any in the world.” The book and the play elaborated on the same themes. It’s no wonder Garfield found it stupid and malignant! But apparently Garfield bore no grudge. On the evening of April 16, 1880, according to his diary, “Crete and I attended a party at Governor Hawley’s given to Charles Dudley Warner [yes, Twain’s co-author]. A very select and pleasant company were present.”

Mark Twain was a “jubilant” supporter of Garfield and the Republican ticket in 1880. A few days after Garfield’s election, Twain spoke to the Middlesex Club, one of the oldest Republican organizations in the country, reporting on his campaign experience. “I did not obstruct the cause half as much as I might have supposed I might in a new career, politics being out of my line. But it was a great time. The atmosphere was thick with storm and tempest, and there was going to be a break, and everybody thought a thunderbolt would be launched out of the political sky. I judged it would hit somebody, and believed that somebody would be the Democratic party…I did not believe we had much to fear on the Republican side, because I believed we had a good and trustworthy lightning rod in James A. Garfield.” Pretty sophisticated analysis for someone who claimed to be a political novice.

But did they ever meet? I did not find anywhere that James Garfield said, “Met Mark Twain today.” Nor did I stumble across a Twain declaration that he met Garfield. They certainly sometimes traveled in the same circles, making a meeting possible, perhaps likely. But I am still without an answer for my nine year old visitor.

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National, May 2013 for the Garfield Observer.