Last updated: October 24, 2022

Article

Development and Modernization: Water Utilities at the Longfellow House

NPS Photo

The Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House is noted for its architectural significance, with its iconic façade reproduced on postcards and replica buildings alike. At its core, however, the house was a home for generations of people while hundreds of visitors went through its doors as guests. Today, calling a building ‘home’ implies the existence of certain standards and a level of comfort: running water, an indoor bathroom, and rooms warm and light enough to enjoy inside activities. Utilities – unremarkable and unnoticed when they work well – provide the comforts of home. Each era brings its own innovations and advancements, from privately managed water access, to the advent of municipal water systems to the modern conveniences of the turn of the 20th century. Diving into a history of public utilities development can be no less interesting than the history of the house interiors and landscape architecture around it. By looking at primary sources and cultural, historical, and archeological reports, we can track the history of water utilities of the house at 105 Brattle Street in the context of water ways development in Cambridge.

Longfellow Family Postcard Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS

Private Water Supply

A small lot of about a third of an acre lying on the southerly side of the lane leading by the botanic garden to the west field & fresh pond so-called… with a spring on said lot used to supply an aqueduct.

“Craigie’s Widow’s Dower,” 1820, Middlesex County Record of Probate1

For the home’s earliest owners, access to water supported their luxurious estates. In the early 1700s, the Road to Watertown, currently Brattle Street, was composed of properties of wealthy citizens. The properties were subdivided according to land use and usually included a mansion house with gardens separated from farms which were often referred as “plantations of fruit”. The Vassalls’ estate was not an exception. At the time when the family of Colonel John Vassall owned the property in the 1740s-1770s, a variety of fruit trees were cultivated on the estate while herbaceous plants were intended for the greenhouse.2

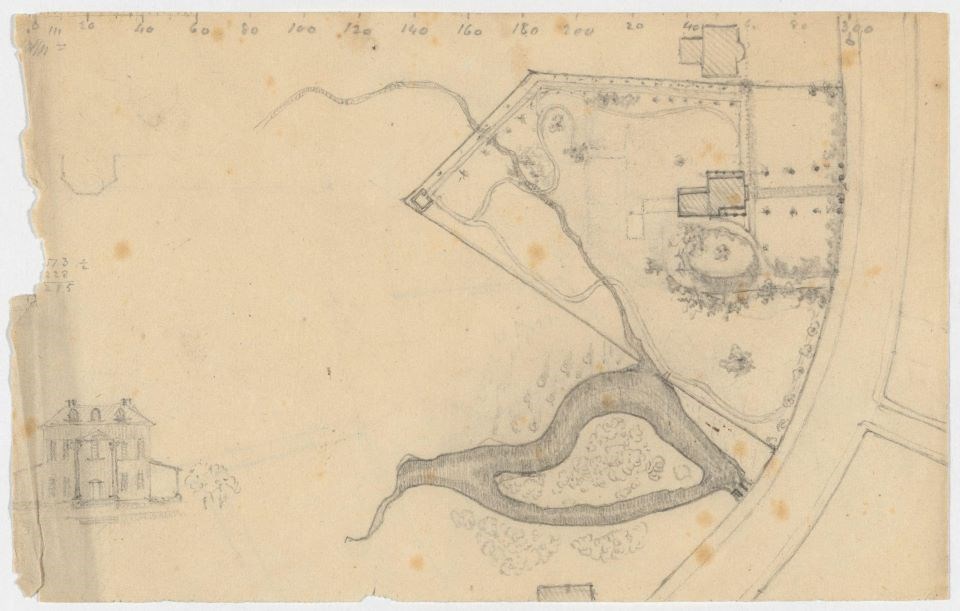

Following the American Revolution, new owner Andrew Craigie expanded these plantings. A plant list for the property which Craigie included with a letter from March 22, 1792 includes tens of names of fruit trees, flowers, decorative and usable plants, many of which were exotic. Water to irrigate the orchards and to probably deliver water into the house came from a small stream that connected marshes around the present Healey Street area with the Charles River. A dam built in 1791 appears to have changed drainage fields to the west into a pond, and by 1820 a watercourse crossed behind the house’s barns.3 The 135 acres of land that belonged to Andrew Craigie served as a working farm with a greenhouse, an excavated pond, and a variety of imported and local trees. Existence of a reliable water supply to provide for all these features was essential.

To ensure a reliable water supply, a wooden aqueduct was installed in 1792, bringing water from a spring on Observatory Hill, which became known as the “aqueduct lot” of Craigie’s property.4 A dry well east of today’s Carriage House had drainage pipes leading into it. A buried wooden water pipe entered the north side of the house lot and entered the house to supply water for the basement. The house therefore had a consistent supply of water during the Craigies’ time, though water was probably brought to upper floors manually.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University. MS Am 1340 (159)

In October 1843, Nathan Appleton purchased the house for his daughter Fanny Appleton and son-in-law Henry W. Longfellow as a wedding gift. The couple lived in the property from 1843 on and made it home for their six children. In a letter to her sister-in-law on December 20, 1843, Fanny Longfellow wrote:

We had a very pleasant visit from Alick which we persuaded him to prolong, after your departure, until he was summoned home. He aided Henry with his engineer skill in drawing maps of our estate which we decorated with rustic bridges, summer houses & groves à discretion!5

Appleton Family Papers, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS

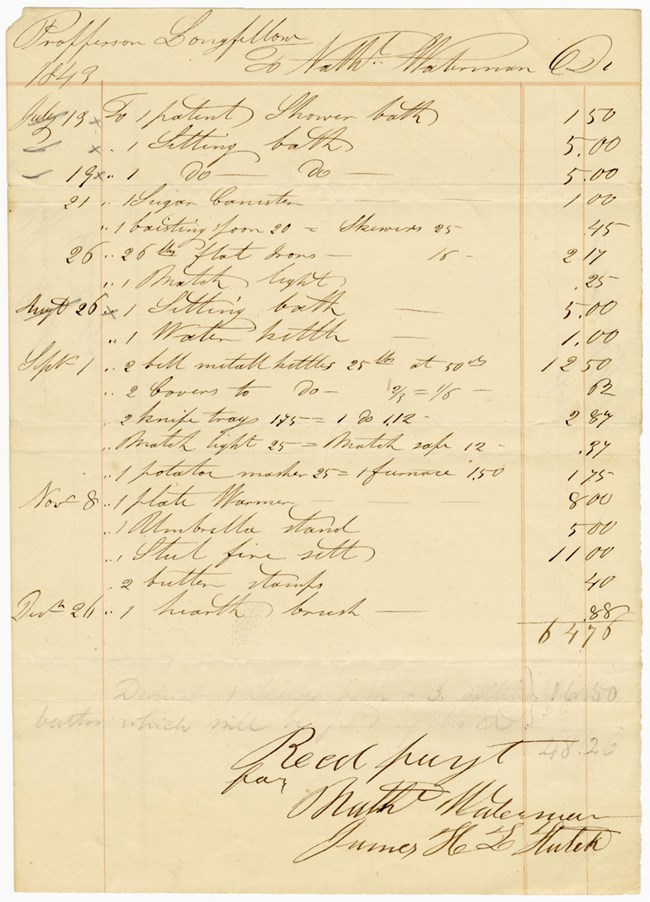

Given its proximity to natural springs, the house received a system of pipes and hand-operated pumps and fixtures as the Longfellows invested in developing plumbing for their new home. A bill from 1844 includes a substantial amount of $386.10 – equivalent to over $13,000 in 2020 dollars – paid to “J. Clark for Plumbing.”6 A receipt from Nathaniel Waterman’s Boston shop itemized a “patent shower bath” and three sitting baths.7 Waterman’s advertisement for the “Improved Bathing Pan and Patent Pneumatic Shower Bath” claimed that “They render the process of bathing easy and agreeable… they afford the best method of performing the healthy practice of daily ablution, at present known.”8 Henry Longfellow evidently believed in its health benefits, writing to his brother-in-law in 1844, “The shower bath is curing my eyes.”9

By 1846, the shower bath was installed in his dressing room “into the wall, with curtains in front” and supplied through a water tank located in the attic over the ell.10 It is unclear from surviving evidence how the tank was filled, but water was most likely brought into the tank manually as pumping it all the way up would have required a complicated mechanism. That year, Henry W. Longfellow proudly demonstrated the shower to his friend, Charles Sumner who, while inspecting the innovation, ended up pulling the cord and getting drenched while fully clothed. As Longfellow recounted:

Sumner rejoices in my shower-bath, - its spacious size, its abundant water, its height of the fall. It is curious to hear him discourse as he stands ready to pull the string: -

"This is a kind of Paradise."

"And you a kind of Adam."

"With all my ribs."

And then the deluge of water descending.11

Though the Longfellows enjoyed the comforts of bathing, their 1843 purchases also included commodes – specialized furniture holding chamber pots – for use in the bedrooms. Upgrades to plumbing would require a public water supply and sewer.

Municipal Water

I made an epigram on the introduction of water into Boston, and the incapacity I feel of writing an ode for the occasion as requested.

Cochituate water, it is said,

Tho' introduced in pipes of lead,

Will not prove deleterious12

Boston, across the river from Cambridge, has the earliest recorded public water-supply system in the country, dating back to 1652, yet for over a century the city had not advanced much in building water works. The supply provided was not sufficient, and the majority of the citizens relied on private wells.13 Piped water was introduced to Boston in 1848, supplied by aqueduct from Lake Cochituate about 18 miles west. The conversion of Frog Pond into a fountain on Boston Common was a centerpiece of the celebration that took place on October 25, 1848 of “the introduction of the pure water of Lake Cochituate into the city.” In his journal, Henry W. Longfellow recorded his experience of watching “the fountain, as it throbbed and rose higher, higher, through the leafless trees, in the rose twilight.”14 This project almost entirely satisfied the city’s demand for water.15 While Bostonians connected to this reliable public water supply in the late 1840s, Cambridge did not advance much further in constructing a public water system. Prior to the Civil War the city of Cambridge relied on a generous chain of natural springs and brooks. For example, Brattle Square had natural springs which supplied water for many houses in the area. It was up to each household to find creative ways of bringing water in – and out.

In 1852 Cambridge Water Works was launched, with Brattle Street becoming one of the first streets mentioned in newspapers where public water pipes were laid. In 1855 the Cambridge Chronicle reported “considerable progress” with the water works, with an optimistic promise to distribute piped water throughout the city by May of the same year.16 Cambridge Chronicle consistently reported on the progress of the water works construction throughout 1856. By April, a brick building to accommodate steam engines, one of the pumps (“a superior piece of workmanship”), and boilers had been completed on Fresh Pond. A network of galvanized iron pipes was constantly growing through the city. Indeed, it was the advancement in usage of steam power and durable, cost-effective cast-iron pipes that made spread of water works possible, first in Europe in the 1700s, and a century later in the United States. The presence of these two factors “prompted the emergence of new private companies” and brought Cambridge Water Works into existence.17 The city was willing to provide service pipes to those households that desired to subscribe by winter 1856. Test trials were made by the Engine Company No. 1 in September 1856 around the Brattle House to work out “the distance to which water would be thrown by the simple head pressure of the water in the reservoir.”18 By January 1856, Cambridge Water Works began to provide services “to a few consumers” and expanded the network of clients by 500 in September of the same year. Overall, 70,000 feet of pipes were laid through main streets of Cambridge by 1857. The Cambridge Chronicle’s issue from November 21, 1857 also referred to “sewers recently built” in the City Affairs section.20

The Longfellows updated their old house, and adopted available technologies, like gas pipes, early. While Cambridge might have been not the first town in the Boston area that installed a public water system, the Longfellow house was probably one of the earliest Cambridge homes that took advantage of the connection to the public water utilities when they became an option.

NPS Photo

Having travelled extensively throughout Europe, Henry W. Longfellow experienced the comfort of indoor baths with faucets of cold and warm water as early as in 1835, which makes him a likely candidate to be one of those few early subscribers to the public water services in Cambridge. In his memoir, the Longfellows’ son Ernest (1845-1931) recalled the house of his childhood: “Craigie and Buckingham Streets had not been laid out, but were cut through and built upon well within my memory. Sparks Street was a green lane with a gate at the bottom on Brattle Street, which goes to show what a country village Cambridge was then. We had in our house neither gas nor water, and I well remember the excitement of us children when the floors were pulled up to put in the pipes.”20 Gas pipes were installed in the house in November 1852, which might be the construction that Ernest, then seven years old, recollected.21

The oldest water closet in the house today is a wash-out indoor toilet in the basement, installed between 1861 and 1882. Family correspondence confirms that the house had plumbing in place by 1862. Henry W. Longfellow wrote to his daughter Edith: “If the nights are very cold, tell Welch to shut off the water, as he did last winter… If anything goes wrong with the pipes send for Mr. Banmeister, the plumber.”22 With municipal water and indoor fixtures came both plumber’s bills and payments for “Water Rates.”23

Architectural Drawings and Blueprints Collection (3002/002-#007), Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS

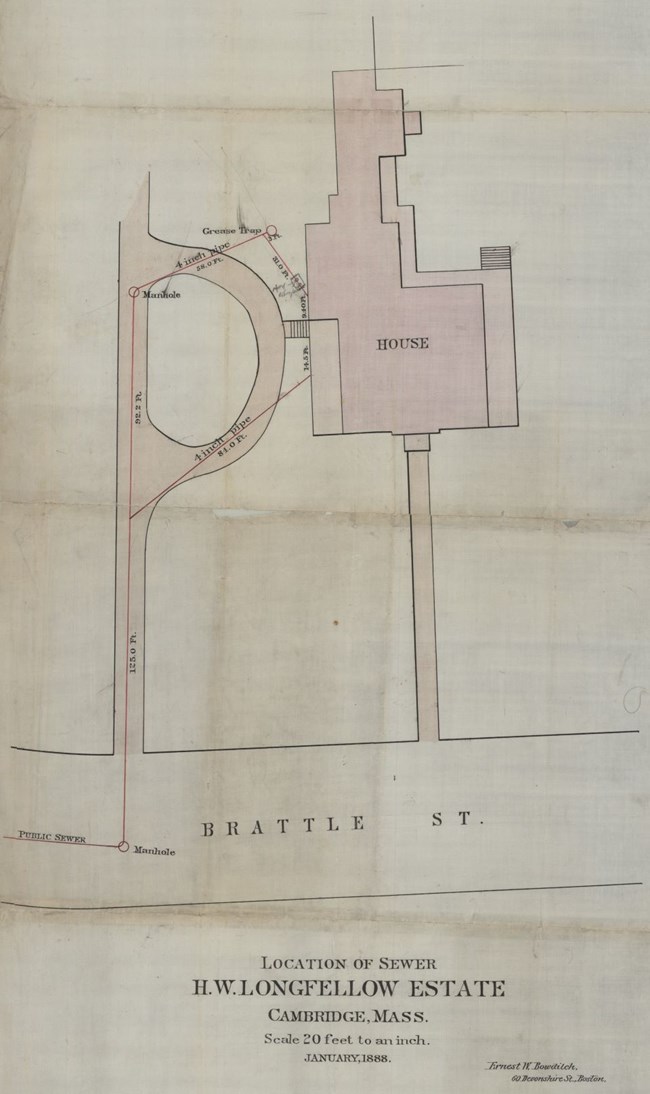

Municipal utilities continued to expand. An 1895 map of Cambridge utilities shows a busy network of gas, water, and sewer pipes grid around Brattle Street.24 The Longfellow House was connected to the public sewer by the late 1880s, and the houses constructed next door for Longfellow’s daughters in 1887 included indoor plumbing as a matter of course.25

Modern Conveniences

After her father’s death in 1882, Alice M. Longfellow continued to live in the house and updated it for her comfort. Most of the existing plumbing fixtures in the house date to her residency. By 1885 there was a fully-plumbed bathroom and two “toilet rooms,” including two on the second floor requiring powerful water pressure.27 By Alice Longfellow’s death in 1928, the house had four full bathrooms and two half baths.

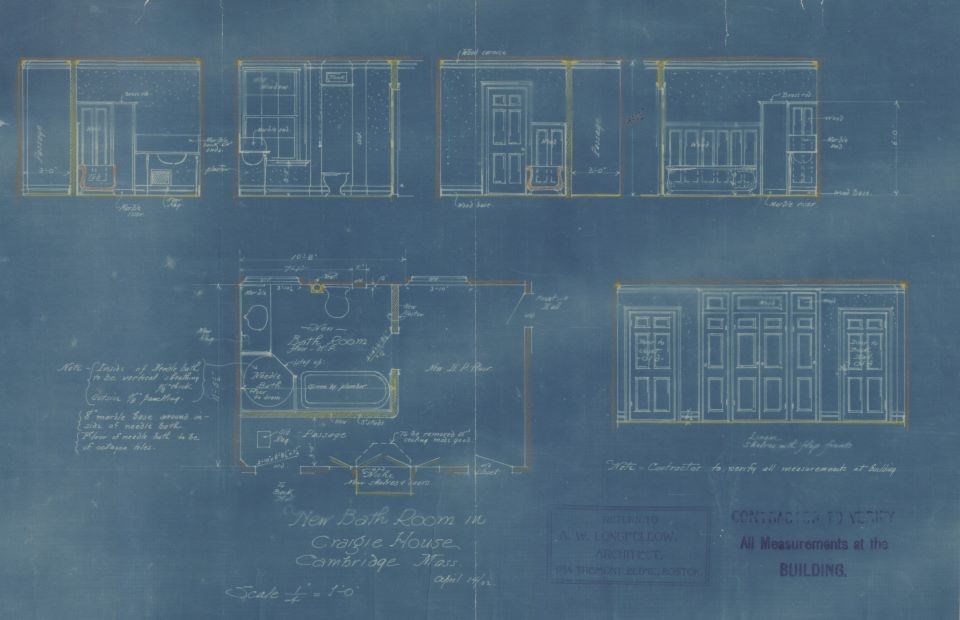

The most significant changes that were brought to the house and the grounds in Alice’s time are the result of the collaboration between Alice and her cousin, the architect Alexander W. Longfellow Jr. (1854-1934). The design records in the Architectural Drawings and Blueprints Collection in the house’s archives track A.W. Longfellow’s modernization of the house. Both as a child and an adult, he spent a lot of time in the house whose historic significance he learned to understand. Under the scrupulous eye of Alice Longfellow, who remained active on a number of historical preservation projects around the country, A.W. Longfellow became an architect of several of the house’s improvements between 1894 and the early 1900s, including expanded utilities. Alice Longfellow’s papers do not include correspondence with her cousin on the installation of new and up-to-date services to the house, and we may only assume that the upgrades were planned verbally. Yet having several architectural drawings may shed light on the transformations in utilities that took place during Alice’s residency.

Architectural Drawings and Blueprints Collection (3002/001-003#002), Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS

During Alice Longfellow’s time the house’s utilities got the appearance that we see today thanks to modernized pipes and sewers which made such desirable features as flush toilets, a tub with hot water, and a shower possible. Alice Longfellow’s spacious needle shower, which directed jets of water all around the torso, came into fashion in the late 19th century and appears on the “New Bath Room in Craigie House” plan of April 1902. It was installed in the new bathroom to help alleviate Alice Longfellow's arthritis. While the first wash-out indoor toilet that appeared in the house between 1861 and early 1882 was “hidden” in the basement and it was likely to have been used by servants, it is during Alice Longfellow’s time that bathrooms became ‘legitimate,’ spacious, and heated rooms.

NPS Photo

The new bathrooms could be easily accessible from the comfort of the second-floor bedrooms and were made a harmonious part of the interiors with painted or wallpapered walls. In the 1902 conversion of Henry Longfellow’s dressing room into a full bathroom, A.W. Longfellow partitioned the bathroom from a hallway, designed wood paneling for the walls, introduced a marble riser around the tub, and created linen closets lining the L-shaped hallway.27 In alterations to another bathroom, he expanded the previous footprint of the room with tub and added paneled walls with glass windows to partition, but connect, to the bedroom next door.

An essential part of any urban infrastructure, public utilities make up part of a framework upon which buildings, cities, and nations are built. Shelter becomes a home when supply of water and energy and removal of waste are all linked in the network. The water closets, showers, and baths documented on architectural records allow researchers to track evolution of public utilities: when a chamber pot gets replaced with a flush toilet and a shower cabin with a manually refilled tank gives way to a heated bath with piped water. Primary sources such as design records, shop bills, newspaper articles and advertisements, and journal entries become sources capable to tell stories of those behind-the-scenes features which made life of the inhabitants more comfortable and sustainable.

- Evgenia Diakonenko, Digital Archive Intern, 2021

- “Craigie’s Widow’s Dower,” Middlesex County Record of Probate, quoted in Appendix C of the Cultural Landscape Report, Vol. I.

- Catherine Evans, Cultural Landscape Report for Longfellow National Historic Site. Volume 1: Site History and Existing Conditions. Boston, Massachusetts: National Park Service, 1993. Accessed 1 December 2021. https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2186272

- Evans, 21, 26.

- Susan E. Maycock and Charles M. Sullivan, Building Old Cambridge (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2016), 264.

- Frances Appleton Longfellow to Mary Longfellow Greenleaf, 20 December 1843. Frances Elizabeth Appleton Papers.

- Nathan Appleton to Dexter for work by J. Clark, 1844. Appleton Family Papers. Like many other bills from 1843-1844 this bill was addressed to and paid by Nathan Appleton, Fanny Appleton Longfellow’s father.

- Professor Longfellow to Nathaniel Waterman, 1843. Appleton Family Papers.

- Sheldon & Company (New York, N.Y.). Sheldon & Co.'s business or advertising directory : containing the cards, circulars, and advertisements of the principal firms of the cities of New-York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, etc., etc. (New York, N.Y. : Printed by John F. Trow & Co., 1845). Accessed 19 September 2022. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nnc1.cu04107039&view=1up&seq=231&skin=2021&q1=waterman

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to Thomas Gold Appleton as postscript to a letter from Frances Elizabeth Appleton Longfellow, 31 July 1844. Frances Elizabeth Appleton Longfellow Papers.

- Marc Vagos, “Presentation of Some Research Finding on the Plumbing of the Longfellow House,” 2 June 1978, 6-7.

Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow, Random Memories (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company: 1922), 22. - Journal of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 14 June 1846. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- Journal of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 17 October 1848. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- J. Michael LaNier, “Historical Development of Municipal Water Systems in the United States 1776-1976,” American Water Works Association, No. 4 (1976): 174.

- Journal of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 25 October 1848. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- Daily Evening Transcript. Boston, Massachusetts. 26 October 1848. Accessed 20 December 2021. https://www.newspapers.com/image/734736048/

- Cambridge Chronicle. Cambridge, Massachusetts. 12 January 1855.

- Martin V. Melosi, Sanitary City. Urban Infrastructure in America from Colonial Times to the Present (Baltimore & London: The John Hopkins University Press, 2000), 23.

- Cambridge Chronicle. Cambridge, Massachusetts. 27 September 1856. Accessed 21 December 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41268694

- Cambridge Chronicle. Cambridge, Massachusetts. 21 November 1848.

- Longfellow, Random Memories, 12. Vagos, 5.

- Frances Appleton Longfellow to Thomas Gold Appleton, 15 November 1852. Frances Elizabeth Appleton Papers. Vagos, 5.

- Henry Longfellow to Edith Longfellow, 4 December 1863. Quoted in Andrew Hilen, The Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Vol. IV. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972), 369.

- Vagos, 8.

- Courtesy of Cambridge Historical Commission.

- Architectural Drawings Collection, 3002/002-#007 and 3002/002-#008.

Ernest Bowditch to Richard Henry Dana III, 30 January 1888, in Series E. RHD III Property, in the Richard Henry Dana III Papers. - Bowditch plan, 1885, in the Architectural Drawings Collection, 3002/001-003#001. This plan shows a toilet room upstairs, an early full bathroom in the upstairs ell, and a toilet room on the first floor.

- Sarah H. Heald, Historic Furnishing Report. Volume I: Administrative and Historical Information, Illustrations, and Bibliography. (U.S. Department of the Interior/National Park Service: 1999), 242.