Last updated: February 2, 2025

Article

Honoring the Unsung Heroes of the 1913 Summit Expedition: Esaias George and John Fredson

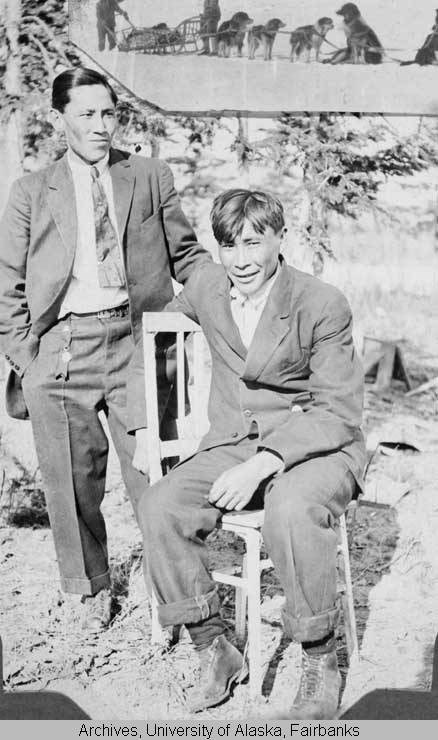

Riverburg, Lawyer and Cora Photograph Album, Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, University of Alaska Fairbanks UAF-1994-70-83A

Denali often celebrates the four men who achieved the first summit of The Mountain in June 1913. Walter Harper, Harry Karstens, Hudson Stuck, and Robert Tatum made history by climbing to the top of North America's tallest mountain, but what about the others who contributed to the expedition? In recent years, efforts have been made to highlight the other two expedition members who provided valuable assistance but never have enjoyed the summit glory that the other climbers have.

Esaias George, who was Koyukon, and John Fredson, who was Neets’ai Gwich'in, did not make it to the top of Mount McKinley, but they were skilled mushers and hunters who provided the crucial freight and basecamp support that helped the trip succeed.[1] Not a lot is known about George's life, which was cut tragically short by the flu in 1920; however, Fredson went on to become a celebrated Gwich'in leader and an important figure in Alaska history.[2]

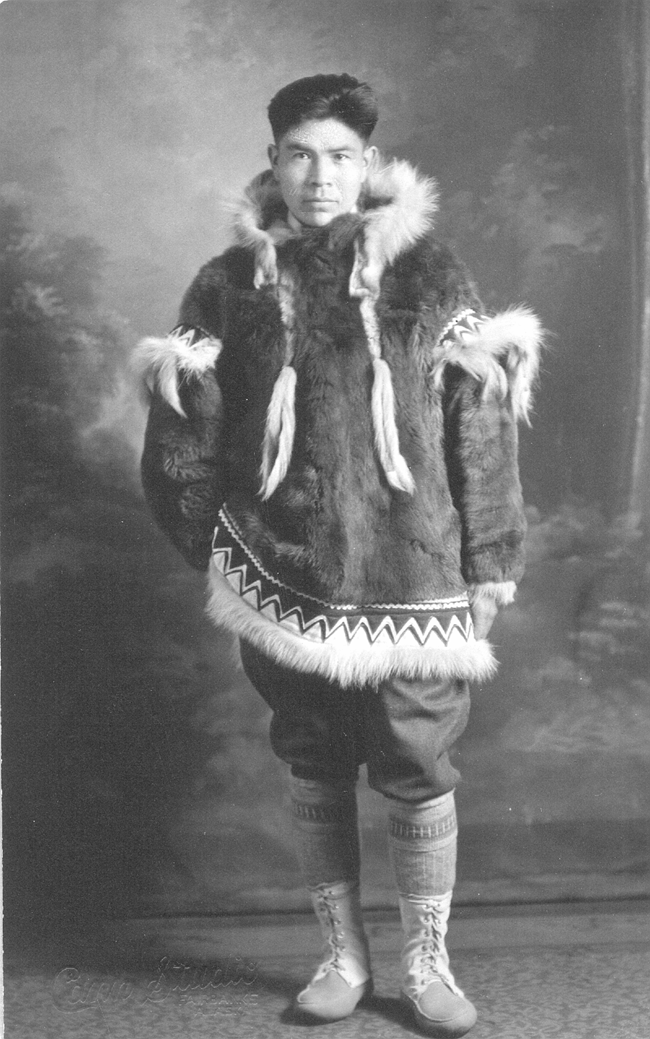

John Fredson (Zhoh Gwatson or "Wolf Smeller"), who remained alone at the Mount McKinley basecamp for 31 days in 1913—patiently waiting for the return of the summiting expedition—was born in 1895 near the Sheenjek River on the south side of the Brooks Range.[3] In 1902, he was left with a nurse in Circle following his mother's untimely death, and was eventually sent to St. Stephen's Mission in Fort Yukon.

At the mission, young John learned English and was mentored by Archdeacon Hudson Stuck, who later helped organize the Mount McKinley summit expedition. Fredson still remained connected to his birth family over the years, and his father took him on hunting trips.

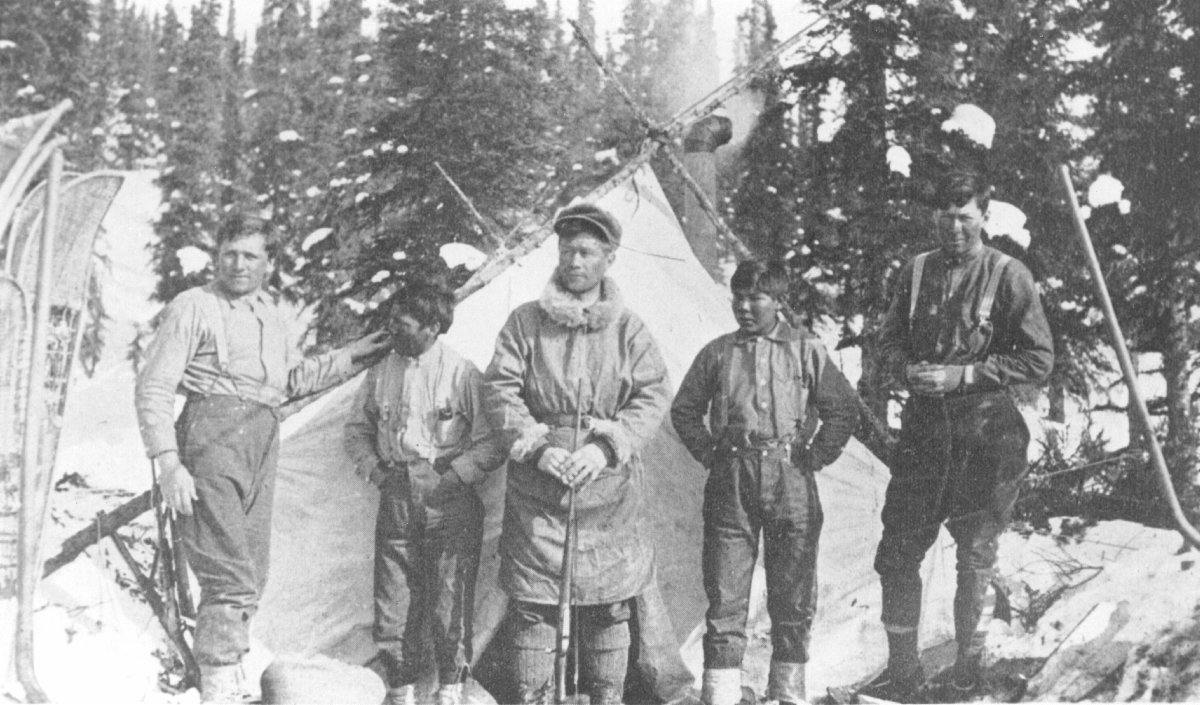

DENA Museum Collection 10728

Following college, Fredson returned to the Denali region and worked for the Alaska Road Commission at Mount McKinley National Park in the summer of 1930.[6] It was not John's first job at the park. During the mid-1920s, the park's first Superintendent, Harry Karstens, helped John find a job as an assistant cook for a summer. In her 1985 biography of Fredson, Clara Childs Mackenzie wrote: "Except for one unpleasant incident when a drunken cook's helper tried to attack him with a butcher knife, John fared quite well."[7]

DENA Museum Collection 22778

In 1945, Fredson passed away from pneumonia and was interred in Fort Yukon. In 1982, the school in Venetie, Alaska was named in his honor. A reburial ceremony in 1996 brought the local legend from Fort Yukon back to his home in Venetie.[9] A member of the Venetie Tribal Council described Fredson as the "George Washington" of the Gwich'in because of his contributions to their sovereignty.

The year 2020 marked the 75th anniversary of John's passing and the 100th of Esaias's death—a good time to remember the two remarkable men who are an important part of Denali and Alaska history.

[1] John Fredson was known as “John Fred” in the early part of his life. When he applied to Mount Hermon boarding school, Hudson Stuck changed “Fred” to “Fredson” because he thought it would help him adjust or assimilate; for more, see: Mary F. Ehrlander, Walter Harper: Alaska Native Son (University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 2017), p. 171.

[2] Records show that Esaias George died in Stevens Village, Alaska in December 1920 (see: Ehrlander, Walter Harper, p. 169). During an interview in 2018, a person close to George’s family mentioned that he passed away in a flu epidemic shortly after the 1913 expedition. It’s possible he was a late casualty of the “Spanish Flu” pandemic that devastated the world between 1918 and 1920 (See: Beth Bragg, “Alaska Native teens get official credit for assisting historic Denali Ascent,” Anchorage Daily News, November 20, 2018).

3] Fredson’s family moved seasonally between the Yukon River and the south side of the Brooks Range, often around the Chandalar River region that is home to the Neets’ai Gwich’in. Clara Childs Mackenzie wrote a biography of Fredson in 1985 called Wolf Smeller: A Biography of John Fredson, Native Alaskan, in which she relays the story of how John’s father gave him the name “Wolf Smeller.” While he was hunting with his father, John grew tired and said, “I smell a wolf,” which he hoped would convince his father to take shelter and a needed break, instead, his father called him Zhoh Gwatsan or “Wolf Smeller.”

[4] At the time, Mount Hermon was a Christian boarding school that sought to help or assimilate Native Americans and Alaska Natives by preparing them for jobs in their local communities, with a goal of bridging Euro-American and Native cultures. Walter Harper also attended Mount Hermon beginning in the fall of 1913 (see: Ehrlander, Walter Harper, p. 84-98).

[5] Some sources such as Clara Childs Mackenzie’s 1985 biography, Wolf Smeller (Zhoh Gwatsan) say he was the "first Alaska Indian” to graduate from an American university with a Bachelor of Science degree; a September 9, 1996 article in the Daily Sitka Sentinel claims he was the "first Athabaskan to gain a college degree."

[6] Mount McKinley National Park was established in 1917, nearly four years after the first summit. The park expanded and changed its name to Denali National Park and Preserve in 1980.

[7] Clara Childs Mackenzie, Wolf Smeller (Zhoh Gwatsan): A Biography of John Fredson, Native Alaskan (Anchorage: Alaska Pacific University Press, 1985), p. 138.

[8] The Venetie reservation was approximately 1.8 million acres. Following the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), the Native Village of Venetie Tribal Government was established and given title to the land for residents of Venetie and Arctic Village.

[9] Congressman Don Young married John Fredson's daughter, Lula, in 1963, nine years before he was elected to the U.S. Congress. The third of John and Jean's children, Lula passed away in 2009.