Last updated: September 17, 2020

Article

The Year Everything Changed: The 1972 Shuttle Bus Decision in Mount McKinley National Park

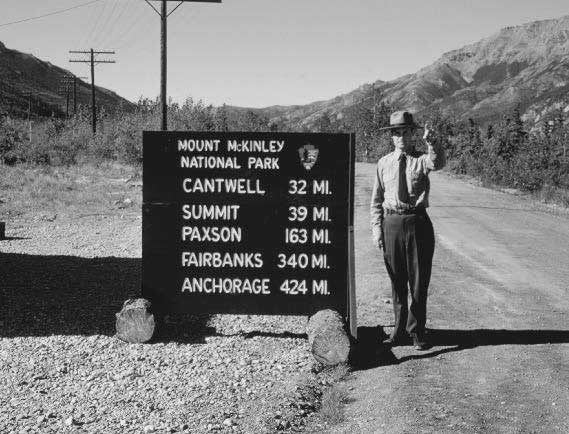

Harry and Norma Hoyt family papers, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage

Wallace Cole Collection, DENA Administrative History Collection, ARO

It is somewhat of a paradox that a large park should have problems accommodating a relatively small number of people. The problem really is not the number of people, but rather the number of vehicles. As we have finally learned by past experiences in other areas, the solution is not to provide more and more roads for more and more automobiles.

Director George Hartzog (1972)

As the Covid-19 pandemic wreaks havoc on Alaska's tourism industry this summer, Denali is bracing itself for a 70 to 80 percent drop in tourism numbers compared to last year. With this projection, the park can expect between 50-60 thousand visitors. The last time the Denali had so few tourists the park had a different name, private automobiles could still drive the length of the road, and Richard Nixon was President—it was the early 1970s.

The early 1970s was an era of big change in Denali. In 1971, 44,528 visitors traveled to Mount McKinley National Park. By the fall of 1971, the Anchorage-Fairbanks highway was completed, and the number of visitors nearly doubled to 88,615.1 In the mid-1960s the park employed 20 permanent staff and 36 summer "seasonal" positions. By 1973, there were still 20 permanent employees but there were nearly 70 summer seasonal employees.2 The decade started with a hotel inside the park and considerable automobile traffic along the Park Road, but it ended with large hotels being built just outside the park's entrance and a shuttle bus required to access the Park Road west of Savage River.3

A Big Change in Visitor Access

The completion of the Anchorage-Fairbanks Highway in the fall of 1971 was the major catalyst for the decision to restrict traffic west of Savage River. Improved park access from two of Alaska's biggest cities led to an expectation that tourism would spike—an expectation that was met immediately when the highway was finished.5 The increase in vehicle traffic was a concern for the park’s wildlife, the ability for the tourist to view the wildlife, and for the capacity of the rustic Park Road to safely handle an influx of traffic.

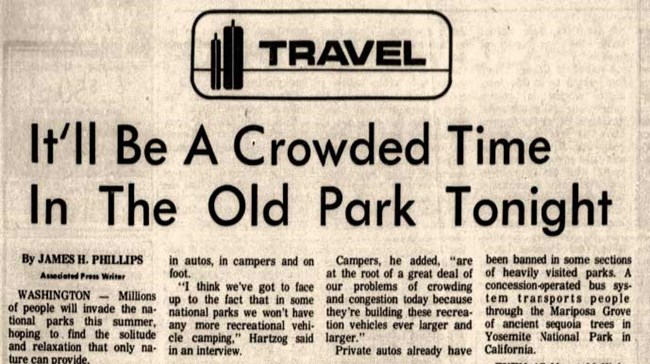

St. Petersburg Times, July 9, 1972

The report outlined the dramatic upward trends in national park visitation which was increasing at a rapid rate in the 1960s and expected to triple by the mid-1970s.8 The volume of visitors coming into national parks would have been inconceivable to managers just ten years earlier. The report went on to warn park managers:

The flood of park users represents either a profound threat to park values or an extraordinary opportunity to make those values a more meaningful part of this nation’s cultural inheritance. . . . The single abiding purpose of National Parks is to bring man and his environment into closer harmony. It is thus the quality of the park experience—and not the statistics of travel—which must be the primary concern. Full enjoyment of a National Park visit is remarkably dependent on its being a leisurely experience, whether by automobile or on foot. The distinctive character of the park road plays a major role in setting this essential unhurried pace.9

Park Road Standards said that national parks and American cities were at a crossroads with automobiles because noise, traffic, and pollution were threatening the quality of both. In addition, development of roads in national parks threatened to scar the landscape and disrupt wildlife. Concern was expressed about the size of new mobile camping vehicles and the type of infrastructure required to accommodate that traffic, which was not feasible or desirable for parks. The report recommended excluding large vehicles from park roads not capable of handling them and instead accommodating them near the park entrance areas.

NPS Photo

In mid-January 1972, Hartzog and other NPS officials were contemplating the decision to close the road to most private vehicles beyond Savage River. In an interview with US News and World Report, Hartzog explained, “One of the great charms of Mount McKinley National Park is its fantastic wildlife displays. Our ecologists tell us that with heavy automobile traffic along the single road into Wonder Lake, wildlife will leave the road.” Hartzog was seeking to balance the preservation of park values with still providing public enjoyment.

In February 1972, Ernest Borgman—the General Superintendent of the newly formed NPS Alaska State Office in Anchorage—told the Fairbanks Daily News Miner that officials were studying a plan to restrict traffic on the road because of the expectation of a dramatic increase in visitation. “We really don’t have any good criteria to base an estimate on, but with completion of the road, we just expect a great increase – it might be 100 per cent, it might be 500 per cent, or it might just be 50 per cent; his first guess was correct, as tourism increased 100 percent from 1971 to 1972).”11

Borgman said that a traffic-congested road would diminish the visitor’s experience at the park, and that safety, in addition to overcrowding, was being considered. He also said that regardless of what leaders decided, they would be criticized by the public: “Either way you do it, you have a public opinion problem.”12 When the decision to restrict private vehicle traffic was ultimately made, Borgman wrote a letter to Alaska’s Congressman Nick Begich defending the plan, stating, “Road improvement would be minimal and less expensive with no additional scarring of the natural scene.”13

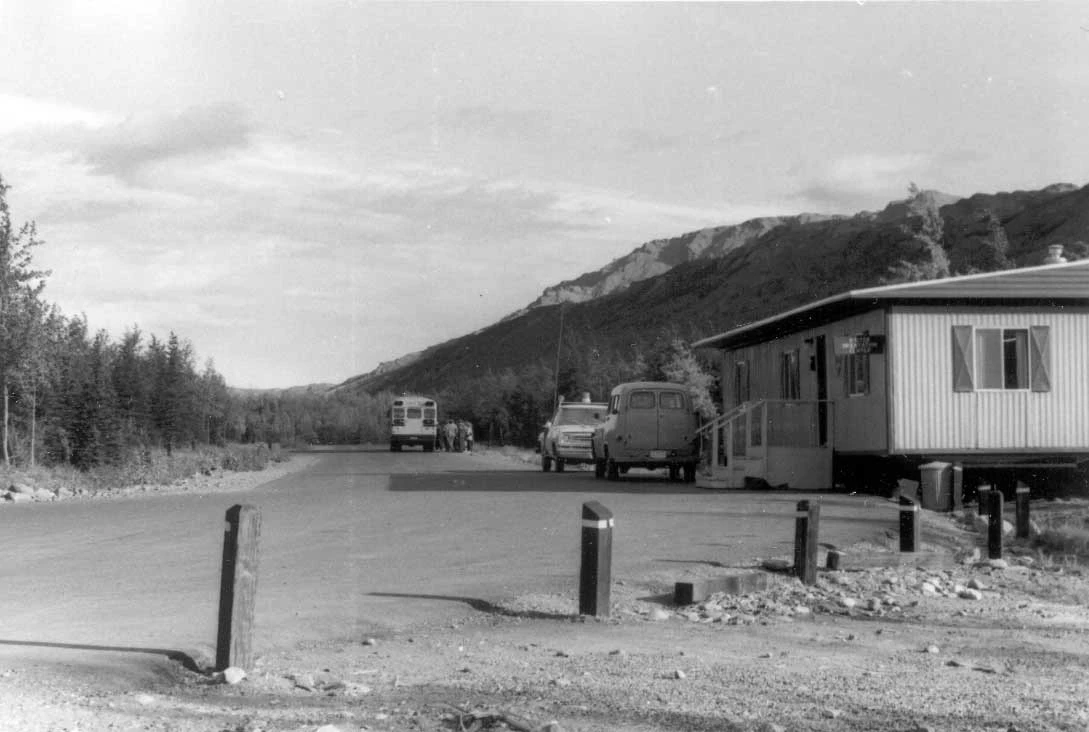

DENA 21660

The park had first seen a dramatic rise in vehicle traffic following the completion of the Denali Highway in 1957. That highway allowed road system access and brought to the park an increase in tourists and tourist facilities. The NPS’s “Mission 66” program called for the improvement of infrastructure throughout the system—including paving and widening the Park Road. The calls for paving the Park Road and changing its standard alarmed scientists like Olaus Murie and Adolph Murie—who had spent decades studying the park’s wildlife.

The Muries were not the only ones concerned about the impact of new infrastructure and the increase in automobile traffic. In 1971, Cathy Brickey, a seasonal ranger-naturalist, wrote an op-ed to the Fairbanks Daily News Miner and described some of the ecological destruction caused by oblivious tourists that she observed. Numerous trees were cut down by visitors at Wonder Lake, and disturbing amounts of litter were discharged from vehicles traveling the road. Her biggest concern was the feeding of wildlife:

It was a point of pride for Brickey that Mount McKinley National Park was one of the last wilderness parks of its kind in the world. The prospect of more oblivious tourists, following the completion of the highway under construction, was a cause for alarm and could potentially cause what she called, “monumental ecological disruptions.”The most imminent ecological damage stems from the feeding of animals who may happen to wander alongside the road. Animals, like people, can hardly refuse a handout. But what the unsuspecting visitor does not realize as he tosses food to the bears, foxes, and even the ground squirrels, is that he is, in one way or another, signing the animal’s death warrant. If the animal is a large one, like the grizzlies in McKinley, he will quickly learn that automobiles are a source of food, and he will ultimately have to be disposed of by the authorities to save some foolish person’s life. If the animal is not killed outright, he is destroyed in the sense that he is no longer permitted to live his own natural way of life. His normal patterns of hunting and survival are affected, and the ecological balance has been disturbed.15

In early 1972, it was decided that road travel beyond the Savage River would be restricted to buses. A limited number of people were allowed to drive private vehicles if they had a campground permit. Kantishna landowners and some professional photographers were also issued permits to drive private vehicles. Some Alaskans protested, including local business owner/resident Gary Crabb who said, "Now they [the NPS] propose to make McKinley Park a Washington Monument but with no elevator." Other people were encouraged with the planning foresight. George Fleharty—the president of Outdoor World, Ltd. who owned the park’s concession contract—openly supported efforts to reduce vehicle traffic. When Fleharty gave the keynote address at the annual Alaska Visitor Association convention in 1971, he pled for comprehensive land use planning because he witnessed the overcrowding and ecological damage caused in California.16 He said that Yosemite was famous for its landscape features but also for being crowded and full of garbage.

Ginger Burley Collection, DENA Administrative History Collection, ARO

Following the implementation of the shuttle bus system in 1972, park visitation continued its steady rise. By 1986, annual visitation had increased to 529,749—going up nearly 600 percent in just 14 years. The General Management Plan (GMP), which was published that year, addressed increasing concerns about vehicle traffic negatively affecting the park's wildlife (this was despite traffic already being restricted since 1972). The GMP set vehicle limits to 10,512 per season (5,094 tour and shuttle buses, 3,664 private vehicles, and 1,754 NPS vehicles), which aimed to reduce total traffic nearly 17% from the totals in 1984.18 The 2012 Vehicle Management Plan (VMP) approached the traffic issue with an aim to improve the relationship between traffic and wildlife by replacing the seasonal traffic limit outlined in the GMP with a limit of 160 vehicles per 24-hour period.19

Denali's shuttle system is the longest continuously running shuttle system in the NPS, and—with an approximately 150-mile round trip traveling distance—it is the most extensive. The national significance of its nearly 50-year-old shuttle bus system is one of the reasons the Park Road currently is being considered for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. Thanks to its shuttle bus system, visitor access into Denali has been historically unique, but in recent years, other national parks have added shuttle systems. Acadia, Zion, Grand Canyon, and Rocky Mountain National Parks all use buses to reduce traffic congestion and air/noise pollution, in an effort to protect resources and improve visitor experience.20

With the National Parks System having its four highest visitation records in the past four years (2016-2019), it's likely that other parks will follow suit with shuttle access or consider new ways to sustainably carry out the duty of promoting park lands while preserving them from impairment.

In summer 2020, for the first time since 1971, private vehicles have an opportunity to travel the Park Road before the road lottery in September. Coincidentally, the last time private vehicles had this much access to the Park Road was in 1971, the year before private automobile traffic was restricted, when the number of tourists visiting the park was similar to the number of visitors predicted for summer 2020.

DENA 10508

1 Frank Norris, Crown Jewel of the North: An Administrative History of Denali National Park & Preserve, Vol. 1 (Anchorage: National Park Service, 2006), 283.

2 "McKinley park awaits new season," Fairbanks Daily News Miner, March 16, 1973.

3 The McKinley Park Hotel burned down in September 1972 and was replaced with a "temporary" hotel (made of train cars and modular units) that operated until 2001; construction on the McKinley Chalets began in 1978 in the area that would become known locally as "Glitter Gulch."

4 Buses were not new to the road; visitors used them to access the park beginning in the 1930s.

5 When the highway opened, the distance from Anchorage to the park entrance was 240 miles (a reduction of 184 miles). The distance from Fairbanks to the park entrance was down to 125 miles (a reduction of 215 miles); previous access, for both cities, was via the Denali Highway, which required traveling to Paxson on the Richardson Highway. The Anchorage-Fairbanks Highway was officially named the George Parks Highway in 1975, in honor of the Alaska Governor who served from 1925 to 1933.

6 Hartzog respected conservationists and was a supporter of the 1963 Leopold Report which emphasized an increased role for natural resource values in national park management. Despite his efforts to respect scientists and leading conservationists, Hartzog was despised by some environmental groups as he tried to balance recreational opportunities with natural resource values.

7 National Park Service, Park Road Standards (May 1968).

8 National parks had 61 million visits in 1965, 103 million in 1966, and the report projected 300 million by 1977.

9 NPS, Park Road Standards.

10 "'Gateway' national park is considered," Fairbanks Daily News Miner, August 10, 1971.

11 "McKinley chiefs plan closing road to traffic," Fairbanks Daily News Miner, February 3, 1972.

12 Fairbanks Daily News Miner, February 3, 1972.

13 Ernest Borgman to Nick Begich. Draft letter, c. Oct. 1971 (DENA Archives).

14 Norris, Crown Jewel of the North, Vol. 1, 219.

15 Cathy Brickey, "Man can be destructive," Fairbanks Daily News Miner, April 5, 1971.

16 The Alaska Visitor Association merged with the Alaska Tourism Marketing Council in 2000 and formed the Alaska Travel Industry Association (ATIA).

17 "OWL looks at McKinley Park," Fairbanks Daily News Miner, February 22, 1972.

18 Frank Norris, Crown Jewel of the North: An Administrative History of Denali National Park and Preserve. Vol. 2, General Park History Since 1980, Plus Specialized Themes (Anchorage, AK: National Park Service, 2008), 402; Norris, Crown Jewel of the North, Vol. 1, 283; Denali National Park and Preserve, General Management Plan, Land Protection Plan, Wilderness Suitability Review (Denali National Park and Preserve: National Park Service, 1986).

19 National Park Service, Record of Decision, Final Environmental Impact Statement, Park Road Vehicle Management Plan, Denali National Park and Preserve, Alaska (Denali National Park and Preserve: National Park Service, 2012).

20 Yosemite instituted the first shuttle system in 1967, and still uses a seasonal shuttle system.