Last updated: January 18, 2024

Article

Delaware’s Roadside Historical Markers

Article from the proceedings from Are We There Yet? Preserving Roadside Architecture and Attractions, April 10-12, 2018, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Watch a non-audio described version of the presentation on YouTube.

A Sign of the Times: Delaware’s Historical Markers as Roadside Attractions and Artifacts

By Kevin W. Barni - Center for Historic Architecture and Design, School of Public Policy and AdministrationUniversity of Delaware

Abstract

Historical markers, while not typically thought of as roadside architecture, represent early efforts to highlight roadside places, encourage motorists to explore more roadways, and educate citizens about local and regional history. The first part of this paper explores the creation of the Delaware Historical Markers program and the choice to first implement the program along the state’s newest and most innovative highway. Secondly, this paper explores Delaware’s markers as roadside historical resources that are now, themselves, historical, and which must be conserved and interpreted.

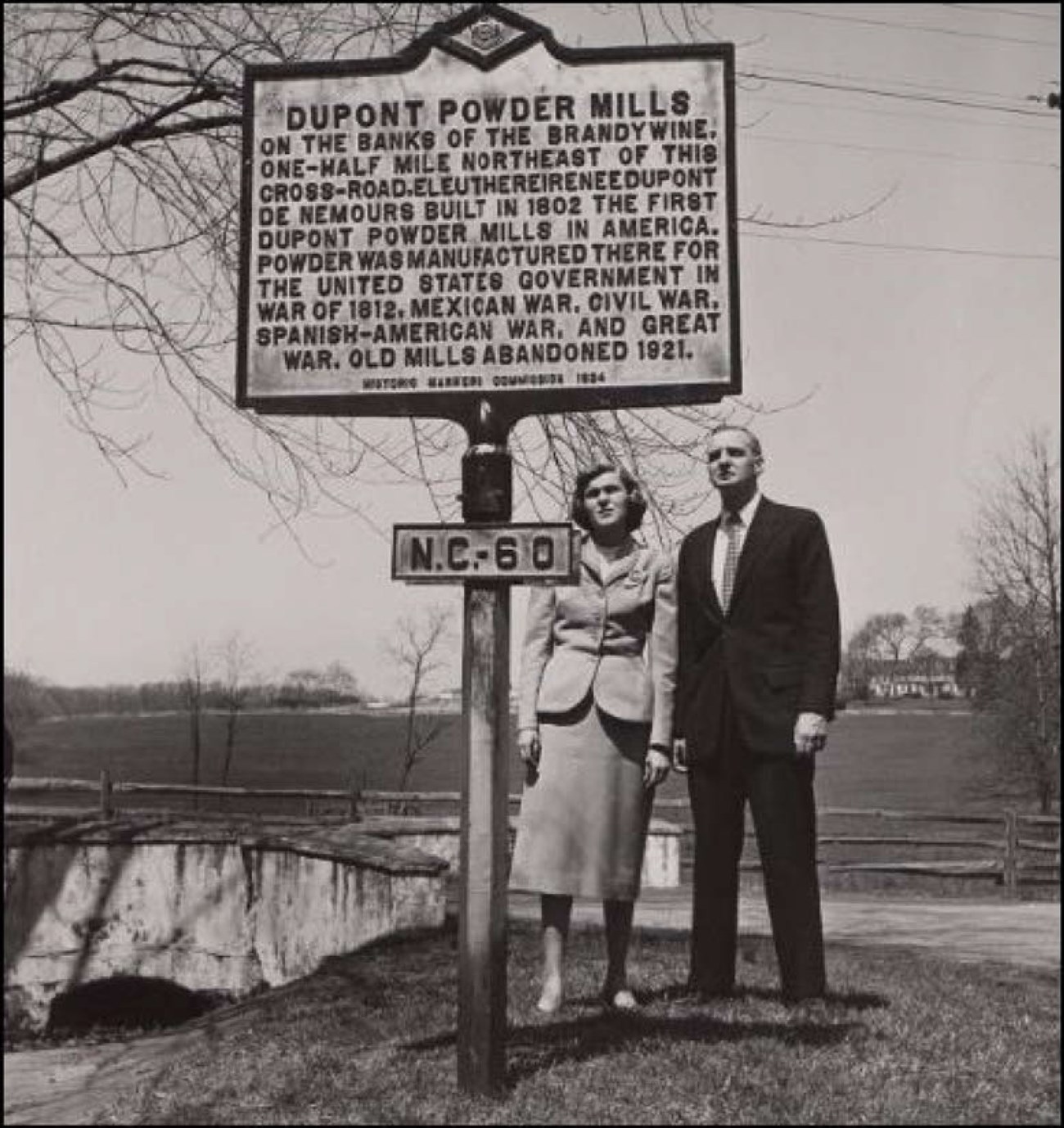

In 1931, a group of concerned citizens petitioned their governor to “mark and memorialize Delaware’s most vulnerable and important historical sites,” an effort that led to the creation of the Delaware Historical Marker program. Just eight years before, a new road that spanned the length of Delaware was completed and gifted to the state by T. Coleman du Pont. The aptly named DuPont Highway connected farmers from rural Sussex County to markets in New Castle County and Pennsylvania and opened the state to increased automobile tourism. This paper examines the complex network of personal and professional interests that went into selecting and placing Delaware’s first 153 historical markers—all of which were placed along or adjacent to the DuPont Highway.

The second part of this paper addresses the conservation, maintenance, and stewardship of historical markers. Delaware’s program now boasts 657 historical markers—one for every three-square miles. Delaware’s small geographic size makes examining these markers, and periodically reevaluating their content, relatively manageable. Yet their placement along the roadside makes markers susceptible to damage or loss from car accidents, snowplows, road widening, and weathering. Many of the markers, being greater than 50 years old, have become artifacts in their own right. Determining how much of a “patina of time” should be retained is a significant complication to their conservation. Further, the earliest text of historical markers—sometimes outdated or incorrect—represents the information deemed “worthy” of commemoration to their contemporaries. Using a combination of photographic documentation, historical maps, and period tour books, this paper situates these markers within the larger context of early automobile culture and explores the ethics of replacing and rewriting markers that are now historic in their own right.

Delaware Public Archives

Delaware’s Historical Markers History and Context

Historical markers represent early efforts to highlight roadside places—encouraging motorists to explore roadways while learning about local and regional history. However, the sites selected, and stories told or, more importantly, those left untold underscore that these early programs were not always as altruistic as perceived. This paper explores three interconnected themes related to the State of Delaware’s Historical Marker program—first examining its early history in the context of the Colonial Revival and Americanization movements, then, arguing for an approach to preserving legacy markers as artifacts of the eras in which they were created. Finally it discusses the implications of preserving, without context, the highly curated early Delaware marker landscape, questioning if this assemblage, with roots in populist ideals of the time, might be seen as a new opportunity to reflect upon how and why we commemorate—a worthy endeavor in today’s political climate.

The establishment of the Delaware Marker Program is situated firmly within the Colonial Revival Movement, and the original catalog of markers compiled by the Delaware Historic Marker Commission in 1929 focused heavily on Delaware’s Revolutionary and Colonial history. Historians attribute the beginning of Colonial Revivalism to the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876, intended to highlight modern technology, while also celebrating the 100th anniversary of American Independence. The Centennial Exhibition fueled an interest in “America’s Golden Age” [1] ushering in an era of fascination with the nation’s past.

The movement, however, was not only about commemorating the nation’s history; it was about legitimizing places and communities through ties to the past. This newly awakened interest in the Colonial era arose during a time of great change in the nation. During the last quarter of the nineteenth-century, economic production shifted away from agriculture to industry [2], and the Industrial Revolution sparked the need for more wage laborers. To fill the demand, an influx of Chinese and European immigrants arrived in great waves. R. T. H. Halsey, a leading proponent of the Colonial Revival Movement, wrote anxiously “The tremendous changes in the character of our nation, and the influx of foreign ideas utterly at variance, with those held by the men who gave us the Republic, threaten, and unless checked, may shake the foundation of our Republic.”[3] The promoters of the Colonial Revival Movement hoped to regain and retain the “real America” by promoting art and architectural styles from our nation’s past, and by preserving patriotic stories and sites associated with America’s early history. The Colonial Revival movement reached its zenith in the 1920s, and during this time, genealogical and historical societies also increased significantly in number, linking their families, communities, and towns to Revolutionary heroes and a romanticized Colonial past—a movement now known as “associationism.”[4]

It was within this climate that the first historical marker programs appear—with the state of Virginia leading the charge. The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, founded in 1889, erected the first statewide historical markers in the country. Their goal, reflective of the morals and ideals of the Colonial Revival movement, promoted and encouraged traditionalist views of Virginia history—celebrating the Colonial past while promoting the traditions of associationism. [5]

The Delaware markers program was also a product—even if indirectly—of the related Americanization movement, which sought to show immigrants the “spirit of America, the knowledge of America, and the love of America.”[6] In 1918, a group of 80 prominent Delawareans, under the leadership of Pierre S. du Pont, formed The Service Citizens of Delaware. The group primarily focused on housing and school reform; instituting programs often targeted to serve the African-American community. They also offered “Americanization” classes during the 1920s, teaching eastern and southern European immigrants “English and the knowledge of their adopted nation.” Historian Paul C. Violas states that “Delaware’s Americanization class was a ‘soft’ assimilation program,”[7] but its existence clearly reveals prevalent anxieties surrounding growing foreign-born populations—anxieties that sparked and propelled the Colonial Revival movement, Americanization programs, and commemorative efforts like historical markers programs. In a small state like Delaware, the same networks of wealthy philanthropists and reformers were behind many of these patriotic statewide initiatives.

The Delaware Historical Marker Commission formed in 1929, after several patriotic societies and citizens petitioned Governor C. Douglass Buck for a statewide program designed to commemorate and recognize Delaware’s history. Buck’s familial relationships and social connections certainly influenced his civic-minded marker program as he married into the du Pont family in 1921 when he wed Alice du Pont. His new father-in-law, T. Coleman du Pont, was personally responsible for the construction of the first highway to span the entire length of the state, and he gave Buck the job as the chief engineer of that project from 1921 until his election as Governor in 1927. The DuPont Highway, created as a public road constructed and paid for by personally by T. Coleman DuPont, was gifted and dedicated to the citizens of Delaware on July 2, 1924.[8] It is not surprising that one of Buck’s first gubernatorial commissions centered on the creation of a historic marker program that placed an overwhelming majority of its markers along the newly created DuPont Highway.

Buck appointed seven affluential Delawareans to conduct a statewide survey of historic places and notable events worthy of commemoration. His commission made quick work of their tasks— at their second meeting, in December 1930, a year after their founding, the commission had established their list of locations and topics for historical markers.

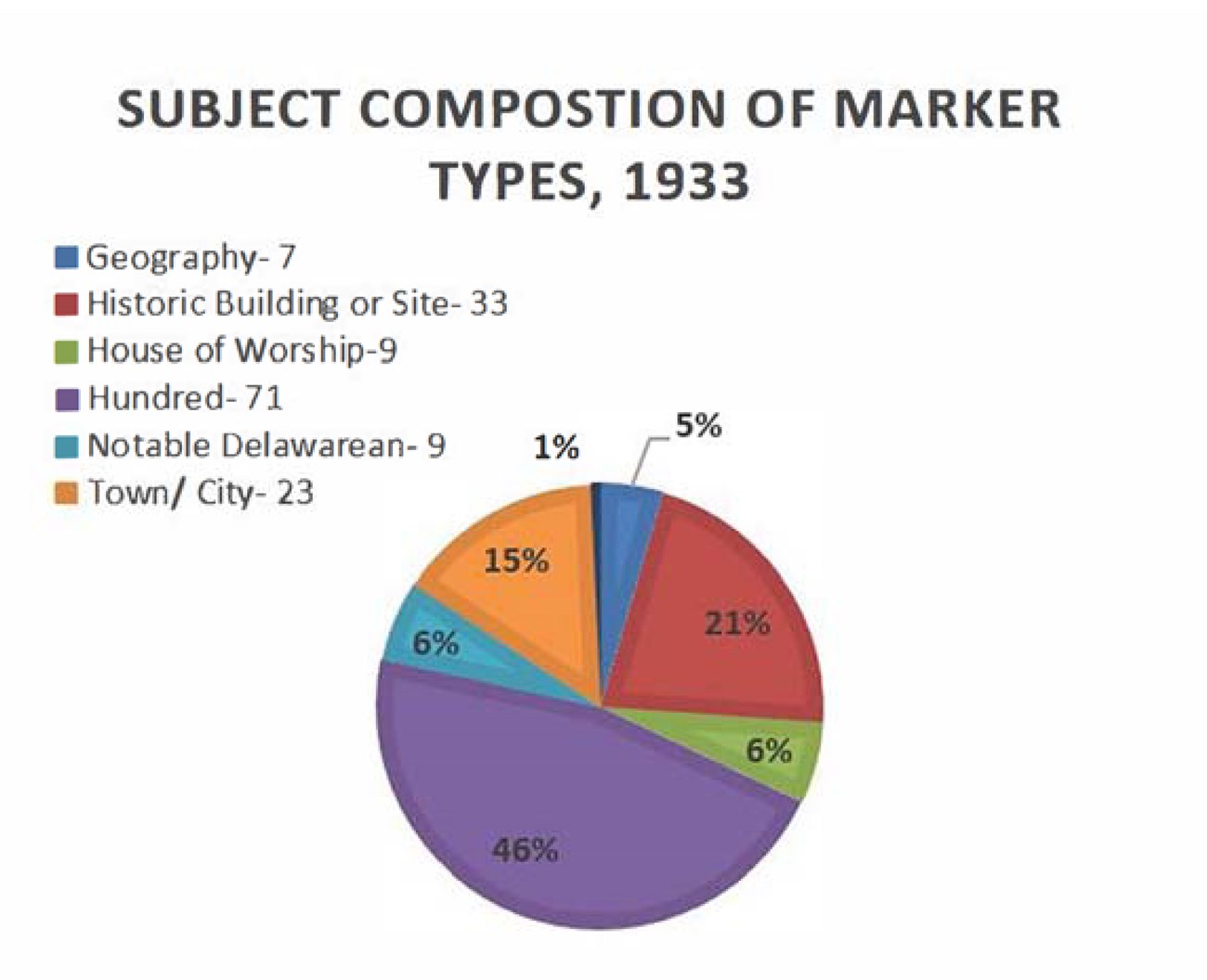

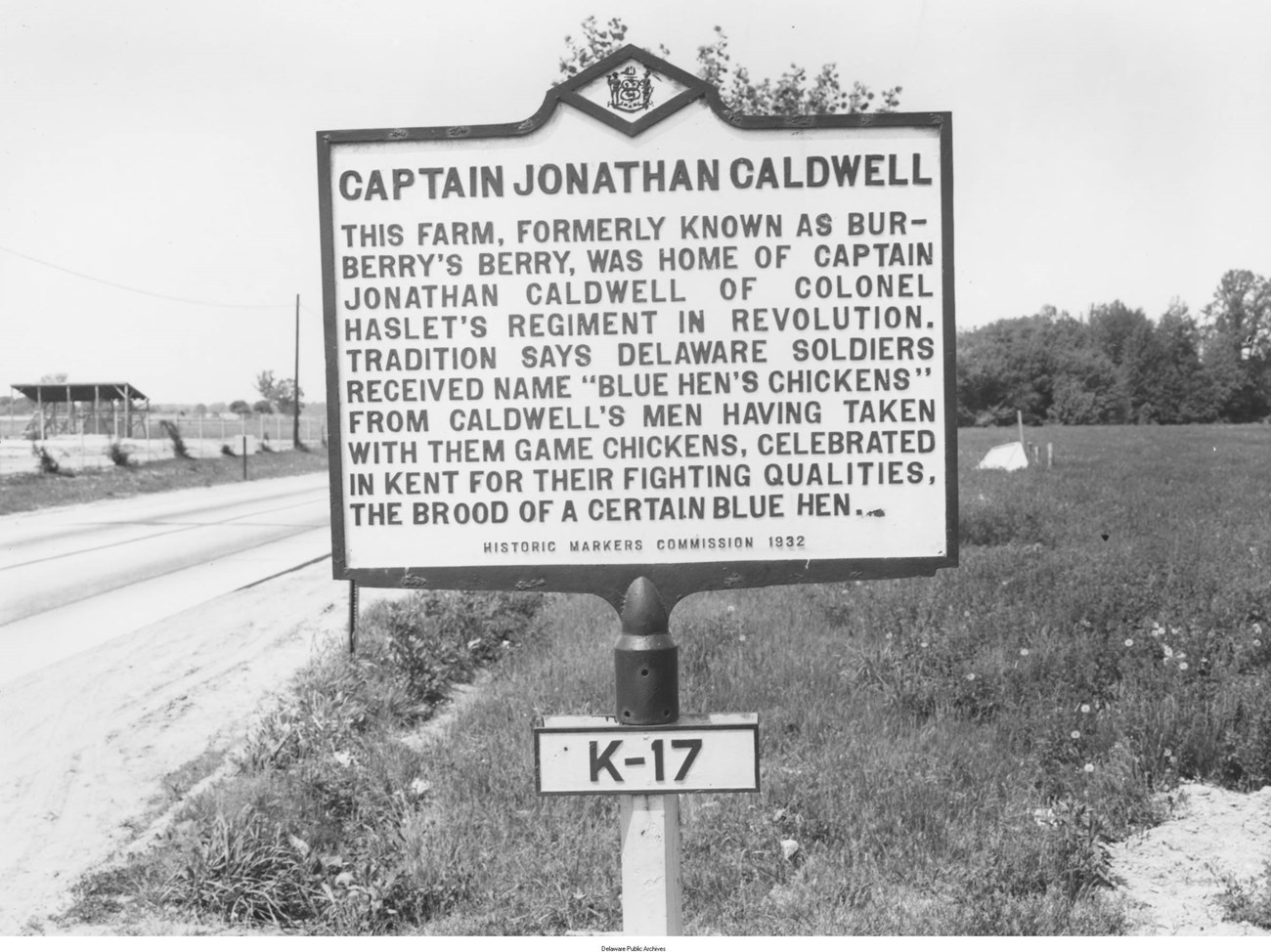

The commission’s selection, which took into account suggestions from the public, highly favored sites that linked places in Delaware to Colonial history. Similar to the early days of the historic preservation movement, the Delaware Marker Commission chose to focus the program on heroes of the Revolutionary War. New Castle County, the northernmost and most densely settled county in Delaware, contained the most markers—and had a clear brand to the stories they established. Remarkably, over one-third of the initial markers, 20 out of 59, mentioned George Washington—an obvious attempt to legitimize Delaware’s Colonial past, while reminding roadside readers of the Anglo-American origins of the nation.

Demographics were not the only thing rapidly changing in Delaware during the 1920s. Concurrent with the evolving social and cultural scene in the state was the quickly expanding transportation network—facilitated by a boom in automobile ownership. By 1930, during the early days of the establishment of Delaware historical markers program, there were 23 million cars on U.S. roads.[9] The national Good Roads Movement sought to stimulate road improvement through better road construction methods and materials, and to provide local governments with information conducive to improving farm-to-market travel.[10] Privately financed roads, like the monumental “DuPont Highway” which spanned the entire state of Delaware after 1923, facilitated the first efforts to create comfortable, long-distance motoring. At the same time, highway associations sought to attract motorists to specific routes that benefited all locations along a highway through the infusion of money from tourists. They marked roads and published maps and guides to aid navigation. [11]

Kevin W. Barni

Delaware Public Archives

Historical Markers and their Curated Landscape

The roadside signage might be interpreted as an effort to establish a cultural narrative on a new landscape that lacked sense of place. Although place-lessness, which refers to a location indistinguishable from other places in appearance or character, is often associated with post-World War II roadsides, there can be little doubt that the new DuPont Highway created a long, wide swath of concrete that blurred sense of place—especially as automobiles facilitated more rapid movement through the landscape.[13] Historical markers, by slowing down drivers and infusing localities with narrative, provided travelers with a sense of place and heritage. The carefully selected history on the markers not only cultivated a sense of place and relayed a particular narrative, but also legitimized the newly created roadside environment through historic events that were no longer evident on the landscape.

Throughout the state, the marker landscape presented narrow scope of content and excluded pieces of history that did not fit within the strict, ideal narrative of the American past. In fact, only three sites were selected which were significant to Native American history (of note is the fact that these narratives only discussed Native American in relation to white history), while no sites were dedicated to women or African Americans. In his work, “The Social Construction of Historical Significance,” preservationist Howard L. Green summarizes this issue neatly by stating;

“Until comparatively recently ‘important’ was defined in narrow social and political terms, and it was uncontroversial. Everyone knew what was important: the homes and other buildings associated with political, military, and business leaders – those who today are sometime derided as ‘dead, white men.’…Historic usually means important to history or well known; historical means associated with things of the past. Simply put, even our label [historic preservation] betrays our elitist origins.” [14]

The Delaware marker commission tapped into the sentiment of the time, and the prevailing understanding of historical significance used by the committee is the same one described by Green. This intentional lack of diversity allowed the Marker Commission to create what, could be considered, a false historical narrative and context, which they pushed onto motorists by way of a small guidebook.

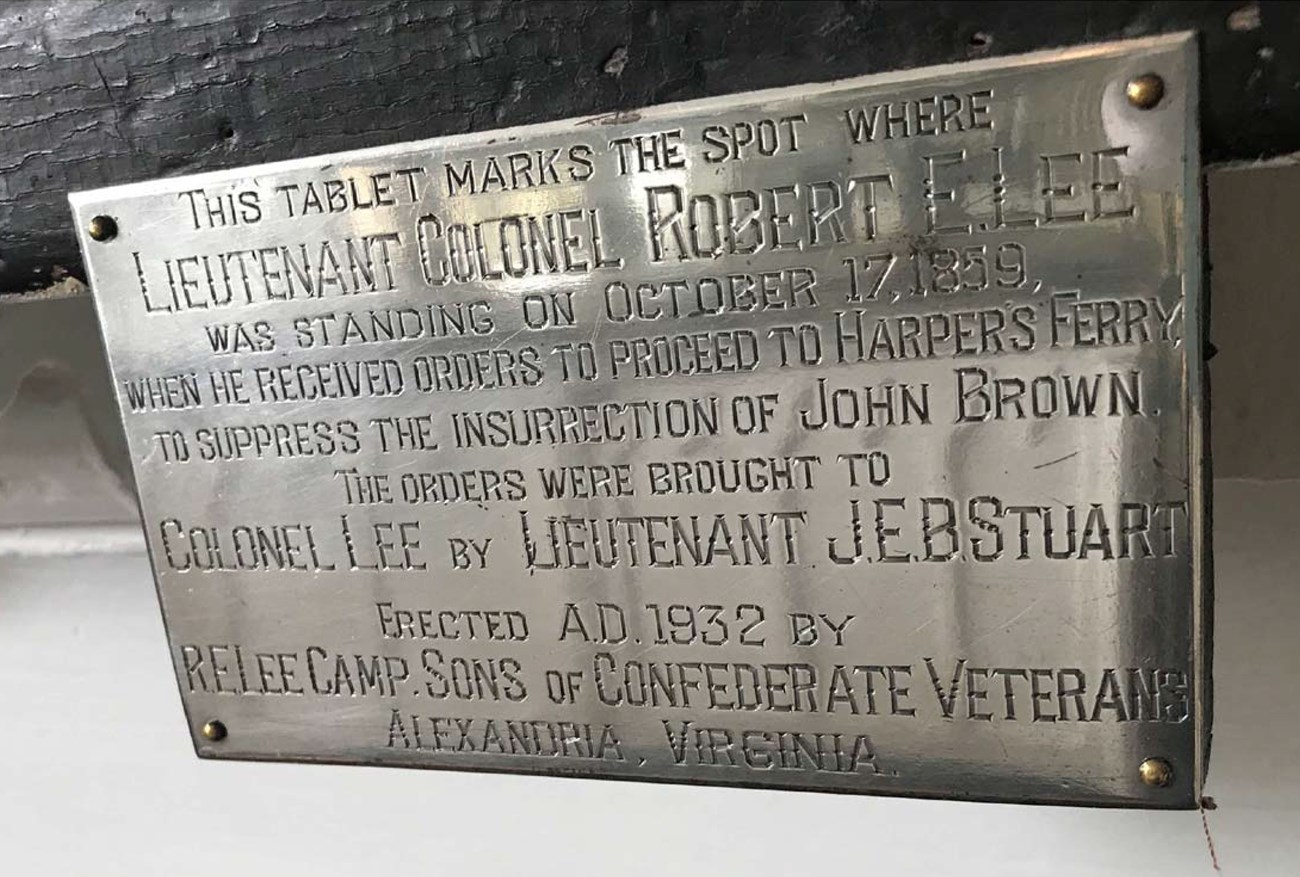

As preservationists John Jakle and Keith Schulle have pointed out, “Celebrating the past can produce not a historical awareness so much as a false sense of what might be called “heritage.’”[15] Heritage speaks not to the past as it was, so much, but to the past as people might wish it to have been. Typically, such assertions assign contemporary social or cultural agendas in the name of an imagined past. To this point, many of the early groups producing markers were proponents of “The lost Cause of the Confederacy” which promoted a “history” significant to them. As L.P. Hartley wrote during another turbulent era, “Heritage activists use the past to find roots, to affirm identities, claim legacies, to celebrate collective bonds and to traduce rivals.”[16]

Kevin W. Barni

Colonial Revival-era historical programs, like the Historic Markers Commission, had mostly noble intentions. These commemorative efforts were a reaction to turbulent times in our nation, and American leaders sought to conjure the nation’s early traditions as a stabilizing cultural force, while also aligning with the past as a way to separate themselves from newly arrived immigrants. However, this need for differentiation and desire to neutralize cultural otherness led to a carefully curated historical landscape, adhering closely to the newly created DuPont Highway, and a collection of historic markers that highlighted one heritage and one dimension of history—to the exclusion of many others.

Delaware’s early historical markers are physical and intellectual artifacts of the early twentieth century. As an assemblage, they represent a landscape of selective heritage designed by the wealthy class, as a way to impose American ideals on the shifting and increasingly placeless national roadside. They sought to legitimize the history of the state through association to what was considered the “golden age of the nation.” This legitimization, located just off the roadway, insured that word of mouth or a guidebook would help foster a stronger state and national identity.

Hagley Museum and Library

So how might we evaluate, interpret, and conserve these culturally-charged objects almost 100 years later? First, consider that the original cast iron historical markers are now, themselves, historically significant, both through being over 50 years old and for embodying a national historic trend, at a state-wide level. Furthermore, early historical markers are among the last vestiges of the earliest roadside architecture that dominated the landscape in the early- to mid-twentieth century in Delaware. So, their conservation and curation is an important historic preservation question, and one that becomes more pressing with time.

Preservation, Restoration, and Interpretation of Markers

Historical markers have a host of condition issues based on the inherent vice of materials used in fabrication. It is unreal to expect that a marker will remain pristine in perpetuity, while outside. Metal, the primary component of all markers, quickly erodes in the presence of water, and given that there is often no shelter for these objects, little can be done to slow the effects of weathering. Additionally, markers face mechanical threats; cars and snowplows are often the cause of their untimely demise. To date 136 or 20%, of total historical markers are considered missing. An additional 202 or 30%, have a condition issues requiring repair or restoration. Estimates, as of December 2017, show it would cost the state $325,000 to $500,000 to adequately address all of the necessary repairs to the existing catalog of markers.

Delaware Public Archives

The remaining cast-iron markers present an additional challenge, as current practice requires sandblasting to remove rust, and to provide a clean surface for new paint. With each restoration, more material is lost, and this begins to wear away the lettering. This makes the markers harder to read with each subsequent restoration.

The Delaware Public Archives, the entity in charge of the marker program, considers 101, or 66%, of the original cast iron markers ‘missing’. This vast amount of loss makes preserving the remaining markers all the more worthwhile, as they are the actual product of the marker commission, and a snapshot of early-twentieth century commemorative efforts. With this in mind, the historical marker coordinator has to reconcile the preservation of historical artifacts and material with the advancing scholarship of the topics discussed on the markers. Herein lies the issue—the early marker text reflects the era in which it was written, while continuing to stand as the official interpretation of a site or event by the state program for modern-day readers. The marker coordinator is currently considering whether to replicate the missing markers, as they were originally created, or to update their text to reflect current scholarship.

Reproduction markers, if chosen, would contain the same text—but would not be the same materials or display the same finish of those initially installed. This has long been a concern from a preservation perspective. The marker program shuttered during World War II due to lack of iron available for production. By 1945, at the close of the war, citizens were upset that 16 markers were missing, and the state archivist, Leon DeValinger, set out to replace them. Upon reaching out to the foundry, DeValinger was dismayed to hear that the manufacture sold the molds, and in the process, they melted the molds down. Any marker produced post-1933 is made from a non-original mold, and currently are made with entirely different materials. The result then, is modern signs with old narratives.

When an original marker needs to be replaced, it provides a valuable opportunity to update the interpretive text and provide better scholarship. For example, a Delaware marker replaced in 2017, near an area called Coin Beach, for “The Shipwreck of the Faithful Steward” was updated to reflect new information learned over the past 80 years about the shipwreck.

The original text read:

“Bound from Londonderry, Ireland to Philadelphia with 249 immigrants, ‘The Faithful Steward’ ran aground on a shoal where she was destroyed by stormy seas with heavy loss of life.”[17]

The revised text reads;

“The Faithful Steward, bound from Londonderry, Ireland to Philadelphia, ran aground on a shoal September 1, 1785 with 249 passengers aboard. Stormy weather drove the vessel toward shore where it became stranded in 4 fathoms (24 feet) of water within 100 yards of the shoreline. Strong winds capsized the ship and 181 passengers, including 93 women and children, perished. Looters soon arrived, carried off trunks of personal cargo, and picked the pockets of the deceased. The ship carried 400 barrels of British copper halfpennies and rose gold guineas. The coins redeposit along the shore after strong storms, giving rise to the name, Coin Beach.”[18]

This is the only marker from the original 153 that features updated text. This rewriting retained the historic intention of the marker, while providing today’s readers with better historical information. With faithful reproduction of the historical signs is now impossible why stymie ourselves with outdated text?

In the decades since the program’s founding there have been changes in attitudes and interpretations of historic events. The selection process for historic markers has also changed. Now, instead of a committee of social elites choosing sites, the public can apply to have sites commemorated, and applicants must ask their state representatives to fund each project. This has led to a more democratized marker catalog, but still results in a landscape of self-selected narratives, instituted only with the required political backing. Yet, to be sure, modern-day markers are more diverse in topic, and are more inclusive of different histories.

Recently, markers and monuments have shifted from solely uncontroversial, mainstream narratives, to include uncomfortable histories and stories of underrepresented groups. Additionally, as our collective conscious reflects on our history, we evolve our understanding of what should not be commemorated. In the wake of the Charleston church shooting in June 2015, several municipalities in the United States removed monuments and memorials on public property dedicated to the Confederate States of America. The momentum accelerated in August 2017 after the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. The removals were driven by the belief that the monuments glorify white supremacy and memorialize a government whose founding principle was the perpetuation and expansion of slavery. Many of those who object to the removals claim that the artifacts are part of the cultural heritage of the United States.[19]

The News Journal, November 21, 1971

Understanding the history, context and motivations behind commemoration, provides a layer of additional significance to our historic sites. The deliberate exclusion of minorities, or statues erected to oppressors directly relate to the prevailing ideas and movements of the time in which they were created. This begs the question: how will the sites, events, and individuals we commemorate during our generation reveal our priorities—and prejudices—to the next generation?

References

- Gross, Linda P. and Teresa Snyder, Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial Exhibition, (Charleston, Arcadia Publishing, 2005.)

- Gross, Linda P. and Teresa Snyder, Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial Exhibition, (Charleston, Arcadia Publishing, 2005.)

- Halsey, R.T.H. A Handbook of the American Wing, (New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1923.)

- Rossano, Geoffrey Louis, Creating a Dignified Past: Museums and the Colonial Revival, (Savage, Maryland: Rowman and Little Creek, 1991).

- Bluestone, Daniel, “Drive-by History” Buildings, Landscapes, and Memory: Case Studies in Historic Preservation, (New York: W.W. Norton and Co, 2011).

- Hertzen, Robert E. and Henry Luce, A Political Portrait of the Man Who Created the American Century, (New York, Schriber, 1994).

- Violas, Paul C. The Training of the Urban Working Class, a History of Twentieth-Century American Education, (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1978) 41-44.

- Francis, Willam and Michael C. Hahn, The DuPont Highway (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2009)

- Abraham, Kenneth S. The Liability Century: Insurance and Tort Law from the Progressive Era to 9/11, (Cambridge, Ma: Harvard University Press, 2008).

- Francis, Willam and Michael C. Hahn, The DuPont Highway (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2009)

- Jakle, John A., “Pioneer Roads: America’s Early Twentieth-Century Named Highways,“ Material Culture 32 (Summer 2000)

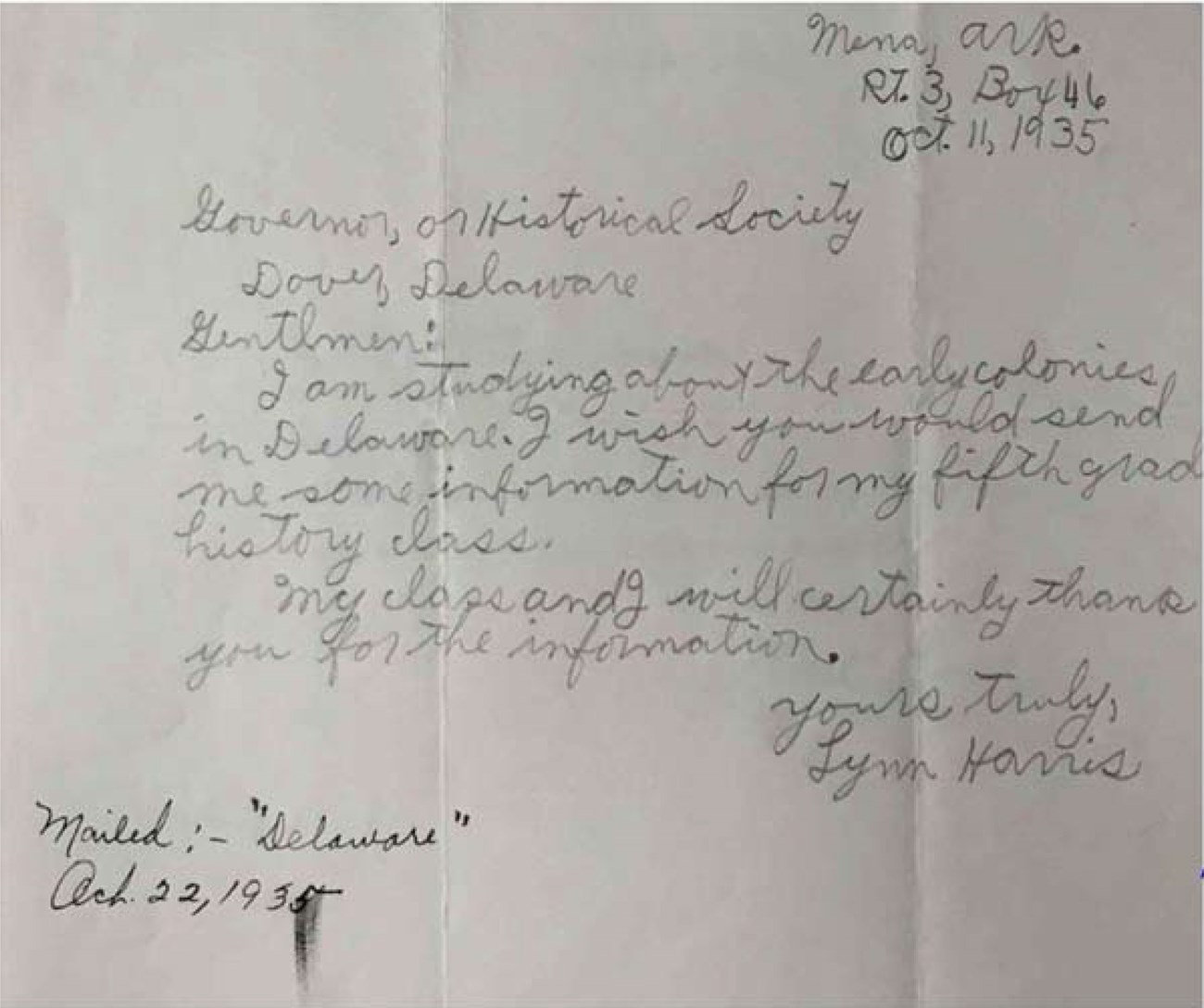

- Requests for Guidebook, 1933-1954, Box 1, Folder 2-3, Historical Marker Commission Files, 1929-1960. Delaware Public Archives, Dover, Delaware.

- Jakle John A. and Keith Schull, Remembering Roadside America: Preserving the Recent Past, (Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press, 2011).

- Howard L. Green “The Social Construction of Historical Significance” Preservation of What, for Whom?, (National Council for Preservation Education, 1997)

- Jakle John A. and Keith Schull, Remembering Roadside America: Preserving the Recent Past, (Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press, 2011).

- Hartley, L.P., The Go-Between, (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1953).

- Delaware Historic Marker Commission, “A Guide to Historic Markers in Delaware,” (Wilmington, De: Historic Markers Commission of Delaware, 1933.)

- Delaware Historical Maker Program, ” The Shipwreck of the Faithful Steward,” Dover, Delaware, 2017.

- Brown, Racheal, "Why the U.S. Capitol Still Hosts Confederate Monuments". News.nationalgeographic.com. August 17, 2017.

- Parks, Miles, "Why Were Confederate Monuments Built?: NPR". 20 August 2017).

- Parks, Miles, "Why Were Confederate Monuments Built?: NPR". 20 August 2017).

- Collins Park Bombings- On February 24, 1959 George, Lucille, and Geraldine Rayfield, an African American family, moved into their new home at 107 Bellanca Lane. As they moved in 300 protesters gathered out front, angered over the news that the Rayfields had moved into the all-white neighborhood. While the family was out on April 6, 1959 an explosion ripped through their house. Undeterred by the explosion, the Rayfields returned to their home. A second blast destroyed their house on August 2, 1959, leaving the Rayfields no choice but to leave. Within one week of the second bombing the police apprehended the bombers who were later convicted of both attacks.

Symposium

You can read other articles from the proceedings of Are We There Yet? Preserving Roadside Architecture and Attractions, April 10-12, 2018, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Or explore other content from the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training (NCPTT).