Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Defend the Adobes: Discriminatory Taxes on Adobe Homes in West Texas

National Center for Preservation Technology and Training

This presentation, transcript, and video are of the Texas Cultural Landscape Symposium, February 23-26, Waco, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of this presentation on YouTube.

National Park Service

Sandro Canovas: Thank you. Yeah, that's true. The other part of my life surrounds around the tradition of Sotol, which is also going through appropriation these days, like the other way, because the Mexicans are not enforcing the denomination of a region. And I have two disclaimers. One is, I don't consider myself an expert on adobe, but I get to play a lot with mud. And the other thing is, I haven't done a presentation in a very, very long time, so I had a lot of material and I split it in two. The first half is the current projects that I do, that are going to lead to the second one. So you can understand why the phenomenon or gentrification and the position of taxes on Adobe homes, and how I handle and how I navigate through the problem that we're facing in rural West Texas.

That first photo is from probably 2008. I was part of the last generation of a construction certificate on the Northern New Mexico College in El Rito, New Mexico, really close to Abiquiu. That's when the first times that I started facing building codes, I decided to get a little more serious and I asked for a scholarship. And I was granted a scholarship to one of the two semesters, the duration of the certificate.

National Park Service

That is Don Santos Chavez. And he's the first adobero (adobe-builder) that I've ever worked in La Junta de los Rios, and that's in Ojinaga, Chihuahua. One of the things that we've been talking about with the cultural landscapes is a situation of a place of a landscape. I happen to be very lucky that I live in an area that we have a river that breaches two countries. So the dynamics of adobes are always switching from one side to another.

And that's, that's Don Santos Chavez. And that story led to my apprenticeship for 11 years with Adobe Alliance. It was a small nonprofit led by Simone Swan that taught adobe construction. She was a student with Hassan Fathy in Egypt in the '70s. And that type of vault that you see there is a Nubian Vault, and it's the oldest vault that we have in human history.

Sandro Canovas, Adobero and Activist

That's the inside of one of the rooms in the house. I remember that the first time that I walked into that room, I got completely seduced by the elegance and the simplicity of the catenary curve of the adobe.

And that's one of the views of the house on the front. And that's Sister Cita Jimenez, an adobero and a master vault mason. Usually, the craft of adobe has gone into plastering, but she's the only woman vault mason that I've had met in that area. She's still alive and she lives in Presidio County.

And these photos that I'm going to continue to show are the eldest adobero that I started approaching during my learning, and my first years. And his name is Don Daniel Camacho, and he was a recipient of a project by Simone Swan by Adobe Alliance. And while I was doing a documentary on the adobero Don Simone and Jesusita and all the adobero , I asked Don Daniel, "Why don't we rebuild again your old kitchen?" Because they had replastered all day. What has happened with a lot of adobes, it's everybody started plastering with cement, which is the worst thing that you can do. So I convinced Don Daniel, and one day when I arrived, he was already putting the foundations. And we put the foundations with stone and mud, and then other ones that he had made.

Sandro Canovas

And I usually tried to invite friends of mine that has mastered something around adobe or vernacular architecture. And that's a friend of mine who was living at the moment in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, and she came all the way to help us build the vault. She has been in Presidio County five times already. And that's how the kitchen ended up being. It shifted a little bit on the original shape of the kitchen, which … That was the house, that was the original house. But this time he told me that he wanted a little bit lower. And instead of the vault being with adobes, he wanted it with fire bricks.

And that's the kids in the neighborhood. Something that was beautiful about that project is that their parents, their moms, would come and tell me that they remember doing the same thing that their kids are doing these days, when the house of Don Daniel was built.

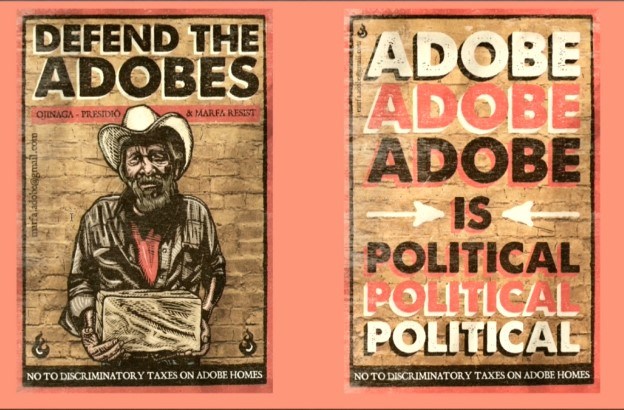

And that's a documentary that I did in 2016 with Don Manuel Rodriguez. And on the left, you're going to see the Rodriguez families. The only one that is still alive is [Jose?], the one with the beard. And Don Manuel and Victor already passed. And that photo, you might recognize it from the poster that I put over there, is the one that I've been using to promote the campaign against the taxes on adobes in Presidio County.

That's Don Manuel and I, talking about how many adobes for vaults we're going to be making for a project. The Nubian vault, which is an adobe form that you see at the bottom of my foot, it's a type of adobe that I have never seen, but Simone introduced it in the early '90s, Simone Swan did.

This is one project that I'm nowadays consulting. Very interesting project near Laredo, Texas, just outside of Mirando City. This is a traditional ceremonial center for the Native American Church. And it links a couple of organizations, but it's called Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative. And it's going to be a conservation place. It's 605 acres, where different tribes are going to be able to come and do their ceremonies.

And we're using adobe. That's Dr. Terry on my left, who's the world leader expert on Peyote conservation out of Sul Ross University. And Mr. Andrew Tso, who's the president of the Native American Church. And that's also that delegation of nine, which all these Indians came from Mexico to lead the Peyote homes. It's very interesting because we're using the adobes and the vaults to do the building of the project.

That's one of the two adobe casitas that I'm restoring right now in Marfa. That photo was taken the last couple of weeks.

That's the apprenticeship that I have, and a couple of volunteers, kids that they just came and asked if they could help. And I love that photo because that tells you a little bit of the intimate moments that people have when they're working together. And the kid happens to be the son of one of my adobedos in Ojinaga.

And that's another house that we are restoring. And our photo of all the local colors of clay that I have harvested within 70 miles from where I live. The only one that is not from there is the very bright orange that it's above my head. And that one, I brought it from the bottom of the Copper Canyon three weeks ago from the town of Urique.

Sandro Canovas

And those are some colors of clay that I get to play. And I do exchange with people. They come and help me make adobes. I go help them. That's a friend of mine that saved … She bought this adobe in auction. And these are the adobes that we're making for our community garden wall.

And that's the next project that I'm going to be doing in May, which is an officer's quarters seven in Fort Davis. It's one of the buildings there.

And I do some altruism and I bring a lot of donations to the Raramuri communities. The Tarahumaras we have in the state of Chihuahua. The Tarahumaras are one of the four groups in Mexico that used the Peyote as a sacrament, and they live in below poverty conditions. I have friend them for years, but my intention is to convince some property owners that they allow us to change these shacks into some adobe buildings.

This is a photo of how you traditionally stack adobes. That allows the wind to go through them, and they last for a long time.

And this photo is about the five minutes of fame that I had two years ago when I got to tour Anthony Bourdain and lot of people recognize me on the … They tell me how it was and I got to show him, to convince him and I dragged him into Ojinaga, so they didn't really did the TV show about Marfa . And that's us having burritos and yes, we were having Sotol at 11:00 in the morning. Yeah, I showed up with a flask and told him, "Don't worry, just drink it."

And it's a confession, I'm one of those Mexicans that when I see signs like this around in Marfa, Alpine, Presidio, my eyes go clink, because I always have something to do with it. I wanted to show these so if anybody knows where Presidio County is, this describes a geographic area. Here in Texas, we call it the Big Bend area. In Mexico, we call it La Junta de los Rios. It's where historically, for example, Cabeza de Vaca spent some time. This is the economics of the place where this gentrification is occurring, is for example, 70% of the County is Mexican or Mexican-American. Some people like to call that indigenous population. The median income is between $19,000 and $24,000. It's one of the poorest counties of the state, and probably the country.

And I wanted to include these photos of adobe landmarks that we have. This is the Church of Ruidoso. David Keller, who's the senior archeology researcher of Sul Ross University, gave it to me a couple of days ago.

That's Fort Leaton, that is managed by the National Park Service. And that photo this morning was sent to me from New York by the Judd Foundation, when I requested some photo of the adobes, because I told them I wanted to talk about the current presence of adobes in Marfa. So Judd, even though Judd arrived to Marfa to build these humongous cement structures, he was aware that the adobe was the original building material.

I went back to Don Santos Chavez because he is the first adobedo I've ever worked. And the elders that I am still very lucky to have in my life. That's Jesusita, who told me how to build vaults and then a friend that showed me how to lay bricks correctly.

These men over here, it's local historian Enrique Madrid. And I went to see him three days ago. And that video that you get to see that I have in my hand, it's a wonderful VHS tape that somebody made called West Texas Adobes From the Ground Up, by an organization somewhere in Austin, and I brought it with me. I want to see if somebody has a digital file of it.

Sandro Canovas

Here, I want it to quote Simone because she had a vision of what was happening there. And I think that one of the biggest problems that I have when I teach adobe construction, it doesn't matter in which context you teach it. It's that people usually relate the adobe to poverty. And what it's very interesting that with this imposition of adobe taxes in Marfa, where in Marfa now, if you have adobe, you pay 57% more than a regular building material. Because when you do an appraisal of a building, always you do the condition of a building and the area, the square footage, never the building material. This is the only place in the world that a tax on the building material exists.

Two years ago, when I went to the Earth Building Conference in Santa Fe, and I brought it to the table, everybody was mesmerized. Because usually, when you build with green materials, you get a tax credit. In Presidio County, you get punished.

And this is the first poster I've ever did with a photo. Too bad that it's not clear, but a friend of mine who owns … He's a Chicano that lives in Presidio but has a small casita in Redford, his grandfather making adobes in Alpine and those buildings in the back, it's Sul Ross University. And he gave me permission to use it. So this is the first flyer I ever did and I would go on the churches really early on Sundays and give it to everybody.

Sandro Canovas

And then I decided to make these posters. I contacted a very famous graphic artist and rapper, a musician in Mexico City, who's a friend of my younger sister. And I told him of the situation and I said, happens that I, I have these ideas. I asked Don Manuel if he would pose. And he said yes.

And I made some sketches with the photo. I put things up and down and I said, "But I need it in Spanish and English." So he gave me these. That's our photo of the day that I took, and Don Manuel during the documentary.

And that's the one in Spanish. This is what I do. It's like Bansky. I put them at night and nobody knows. Well, everybody knows that it's me, but they've never got me. And yes, I tried to make a point of what's going on and I put them on adobes all over town.

And this is not always political. It's a phrase that Simone started using a long time ago, and it says, "Adobe is destined to be politically questioned. Building codes are to be legally corrected through the Southwest of the US beyond. Adobe construction obtains no bank loans. It should and it will. Adobe will be increasingly more of a political issue: As building materials rise even higher in cost than the first decade of the 21st century; as industrial materials' toxicity is perceived, as their cost of transportation increases with the price of fuels; as a climatic comfort and salubriousness of adobe walls are discovered, more budget-conscious dwellers will be drawn to the material."

I would never imagine that 13 years later, this thing that she was saying was actually become reality. And I think these are funny cartoon that I found one day in Simone's drawers, that I sent to the Director of Rural Development of USDA, requesting an interview and he replied, "Yes."

The preoccupying stuff about what is happening with the adobes is that, we're used to talk about gentrification in urban settings. It's always in cities. I had never heard that we're dealing with this in a town of 2,000, you know where people are coming from all over the world and turning that little town into their playground. And I pointed three things that I think are part of it. Is because the greed that the appraisal district didn't know how to compensate their appraisals, the cultural amnesia that we suffer as community members, and the vilification of the earth building materials.

These are photos of some adobes. I lived on this one for a while. I was going to restore it. This is what happens with these taxes, it doesn't allow all the adobes to be restored because the moment that you restore them, you get taxed more, or new ones to get built, so some people are demolishing them or turning into this. And it might be familiar when you see the Donald Judd aesthetic, but going to these turning all that adobe into a cement bunker, it's something that I cannot really handle.

And what I do, is I give free workshops whenever I can. I save some money. These are workshop that we did in November. As a tool, I do radio interviews from friends of mine that specialize in certain areas in constructions, and I fly them over and we talk. I invite the elders, too. The elders, it's a little tricky because they get very shy.

And that's my great grandfather and my grandfather, reason why I landed with adobes, because my great grandfather had brick factories in Mexico City and so did my grandfather. And this is a quote that I wanted to use because, it's by a friend of mine who's an advisor to the UNESCO on earth construction heritage. And it talks about the permanence and what traditions are important.

Sandros Canovas

Speaker Biography

Sandro Canovas advocates for importance of adobe to West Texas and the importance of keeping this indigenous building method alive. His activism has been featured in a recent documentary, which reinforces his message that Adobe is Political.