Part of a series of articles titled The Constitutional Convention: A Day by Day Account for September 1787.

Article

September 4, 1787: The Electoral College

National Archives, https://www.flickr.com/photos/35740357@N03/6166443994/

“This subject has greatly divided the House, and will also divide the people out of doors. It is in truth the most difficult of all on which we have had to decide.”

--James Wilson

Tuesday, September 4, 1787: The Convention Today

The Committee of Eleven which had been charged with working out various unresolved issues released a partial report. The delegates agreed to the first clause of the report without opposition: “The Legislature shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare.” This very broad grant of power—giving Congress the strength to provide for the nation’s general welfare—enabled the federal government to undertake a host of activities, not all of which were foreseeable at the time.

Consideration of the clause describing Presidential elections then occupied the rest of the day. The Convention had repeatedly struggled with how the President should be chosen. Pennsylvania delegates had repeatedly argued for a national election, but most of the delegates thought this couldn’t work in a nation as large and geographically diverse as the United States. The most recent proposal had been to have Congress choose the President, but this violated the concept of separation of powers: if Congress chose the President, the President might not be able to act independently of Congress.

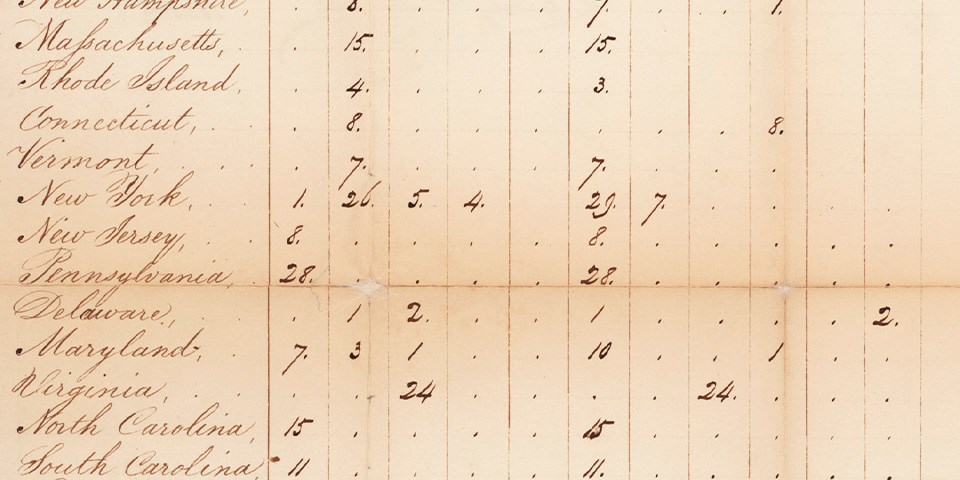

The committee report offered a different solution: an Electoral College. Each state would have a number of electors proportional to its population, and these electors, who would be chosen “in such manner as [the state’s] Legislature may direct,” would in turn vote for the President. Whoever received the highest number of ballots would become President. The person in second place would become Vice President. If no one won votes from a majority of electors, the Senate would choose the President from among the top five vote getters.

Gorham (MA) didn’t like the idea of the person in second place becoming Vice President: “a very obscure man with very few votes may arrive at that appointment.”

Sherman (CT) defended the report, saying that the Electoral College would keep Congress from having undue influence over the President.

Randolph (VA) and Charles Pinckney (SC) were put off that the committeemen had taken it upon themselves to change from the previously agreed to method of election by Congress.

Gouverneur Morris (PA) thought the Electoral College would reduce the risk of a scheming “cabal” picking the President since the electors would be scattered at great distances from each other.

Mason (VA) agreed, but worried that “nineteen times in twenty” no one would win votes from a majority of electors, leaving the Senate almost always in charge of choosing the winner. Baldwin (GA) thought this concern was overblown.

Butler (SC) said the plan was far from perfect but still better than election by the legislature.

Wilson (PA) agreed that the Electoral College plan was “a valuable improvement.” He suggested it would be even better if Congress as whole (not just the Senate) chose the President when no one won a majority. Since members of the House of Representatives had shorter terms than Senators, they were less corruptible and less open to outside influence.

Randolph didn’t like the Electoral College, but agreed with Wilson on how to improve the committee’s idea.

Further consideration of Presidential elections was postponed.

- Congress gained a major power: the ability “to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare.”

- The Committee of Eleven released a report describing how the President could be chosen by an Electoral College.

- Mifflin (PA) and Dayton (NJ) had breakfast with local Jacob Hiltzheimer.

- Johnson (CT) “Din’d Lewis’.” This is almost certainly William Lewis, distinguished Quaker lawyer and defense counsel in many of Philadelphia’s Revolutionary War treason trials, at this time resident at the southwest corner of Third and Walnut.

- Madison (VA) wrote his father to inquire about his health and about events in Virginia. He noted that the price of good tobacco in Philadelphia was forty shillings Virginia money.

- Livingston (NJ) wrote an affectionate letter to his son-in-law, John Jay, asking whether Jay had forwarded the papers to John Tabor Kempe that Livingston had sent him. He wished a reply by next Monday, “because I hope to exchange noise, bustle and formality, for tranquility, blackfish and Sincerity.”

- Carpenter David Evans received six pounds from John Penn for making a walnut coffin for his Uncle Thomas Penn’s servant Sabina Francis. At this time in Philadelphia, most coffins were of pine, walnut or mahogany, and the wood was indicative of economic and social class.

Last updated: September 13, 2023