Last updated: January 18, 2024

Article

Conserving Concrete Artwork in Canada

Part if the proceedings from Are We There Yet? Preserving Roadside Architecture and Attractions, April 10-12, 2018, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Watch a non-audio described version of the presentation on YouTube.

Concrete Jungle: Conserving Canada’s Menagerie of Concrete Artworks

by Kelly H. Caldwell, Sophia Zweifel, and Joseph Sembrat

CSI Conservation Solutions ULC

Abstract

The Centre Street Bridge Lions (1916) and Dinny the Dinosaur (1934) along with the Maurice Savoie Mural (1966) are three examples of large-scale outdoor artworks that adorn the roadways and buildings of Canada. Each with their own unique history and setting, these artworks represent an evolution in style of Canadian outdoor attractions spanning over 50 years. Though these artworks are not directly on the historic Trans-Canada Highway, they span the breadth of Canada’s geography, from the Atlantic to the Rockies. These large-scale artworks act not only as historic works, but serve as intrinsic memories for locals and visitors, especially ‘Dinny’— a favorite of travelers to Calgary since the 1930s.

In 2017, Conservation Solutions ULC (CSI) completed a range of assessments and treatments for the Calgary, Alberta - City Hall Lions and the Maurice Savoie Mural in St. John’s, Newfoundland, and is scheduled to begin work on ‘Dinny’ the Dinosaur, also in Calgary, in spring, 2018. This paper will focus on the historical value of these artworks, discussing their context within their community, along with a review of their preservation needs. It will also review the conservation efforts carried out by CSI, including documentation and assessment procedures, and conservation treatments that ensure the long-term preservation of concrete monuments in the harsh Canadian climate.

Menagerie Artworks

Intangible Value and Community Significance

Public sculptures associated with local landmarks and attractions often find a particularly poignant place in the shared cultural identity of a community. In 2017, contracts to assess and treat 3 separate concrete artworks in Canada gave Conservation Solutions ULC (CSI) the opportunity of witnessing the roles these cherished objects can play within their communities. These artworks spanned the breadth of the country: Calgary’s Centre Street Bridge Lions and ‘Dinny’ the Dinosaur are located on the western prairies, whereas the Maurice Savoie concrete mural is located in the east coast island city of St. John’s, Newfoundland.

It became clear while working with these artworks that all three occupy particularly significant places within the cultural make-up and community identities of their respective cities. A heightened public sentiment was observed while working on these artworks, as community members and stakeholders often stopped to ask questions and offer their personal connections to the pieces. The rooted intrinsic value of these artworks in the local cultural fabric was well known to the city officials in charge of their stewardship and was a significant factor in the decision to invest in the preservation of these works for future generations.

Capitalizing on Stake-Holder Value

The assessment and treatment of the City of Calgary Lions was part of a larger public art assessment project carried out by CSI for the city’s collection in 2017. Even at a time when public art was under a blanket of controversy in Calgary prior to a civic election, CSI observed during their on-site work that the public’s positive reactions about the Centre Street Bridge Lions and ‘Dinny’ the Dinosaur held strong emotional connections. Similarly, in Newfoundland, the Maurice Savoie mural remained a familiar and valued sight for students on the university campus where it is located, as well as for locals who pass it each day on their daily commute.

However much the public loves and appreciates these artworks, they remain particularly challenging to preserve and maintain. Regular maintenance needs for the most part exceed the resources currently available to their owners, and the high costs associated with treating artworks of this scale mean that conservation treatments were not sought out until conditions became critical and the artworks came to pose health and safety hazards for the public. To help gather the necessary funding and institutional support to facilitate the preservation of these artworks, their stewards have worked to capitalize from positive community sentiment through public engagement. For example, as CSI began its work on the Maurice Savoie mural, the treatment was featured on the local public radio station. Public engagement and marketing efforts that included the production of a promotional video were undertaken by the City of Calgary Public Art Program to promote CSI’s restoration of the Northeast bridge lion. While work has not started on ‘Dinny’, the sculpture has been featured in programming for Canada’s sesquicentennial celebrations, and public interest has made the dinosaur’s restoration an ideal candidate for crowdfunding. These forms of positive promotion also serve to garner public support for the preservation of similar, but less popular or known, artworks in the public collections.

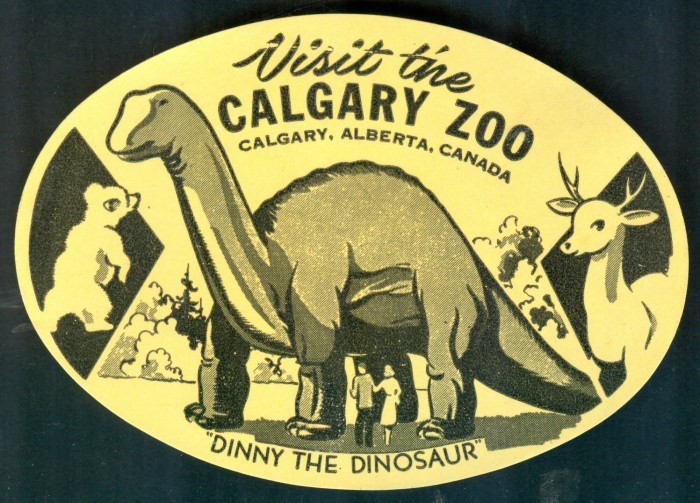

Calgary Zoo

Habitat Challenges

While Canada is known for its frigid winter temperatures, its climate varies vastly between regions. The Centre Street Bridge Lions and ‘Dinny’ the Dinosaur in Calgary are located on the generally dry and sunny northern prairies, which experience large seasonal temperature differences and sometimes severely cold winters. This climate is juxtaposed to the ever-changing, but frequently wet, maritime climate of St. John’s Newfoundland, where the Savoie mural is exposed to high winds, direct sun, rain, snow, and residual salt spray – sometimes all in one day. Recognizing these climate trends helped CSI’s conservators better understand the conditions of each of the artworks, as well as develop treatment plans for them.

These harsh climatic elements only increase the need for regular maintenance and reviews of these concrete sculptures. For instance, frequent and rapid changes in temperature throughout the winter leads to increased freeze-thaw cycling, making shelter coating maintenance and crack monitoring essential to protecting against this type of damage. The short length of warmer months hinders maintenance efforts when it is most conducive to perform these tasks. To further complicate things, access to funding, resources, and training are particularly limited for these public works.

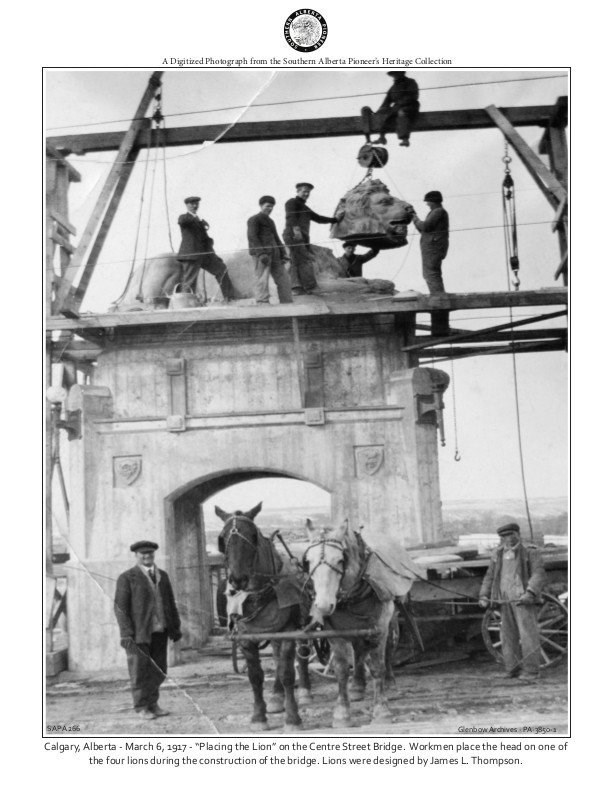

Concrete Anatomy: Calgary Centre Street Bridge Lion

The assessment and treatment of the Calgary Lions was part of a larger public art assessment project carried out for the city’s collection. The four Centre Street Bridge lions were created in 1916 by James L. Thompson and installed on the newly constructed bridge in the winter or spring of 1917. Thompson, a City of Calgary employee, was recruited to carve the clay models for the lions which were based on the bronze lions that surround the base of the Nelson Column in Trafalgar Square, London. The lions were subsequently cast in concrete from the clay models, and the finishing work was done by Dymtro and William Storgyn. The lions were installed on four concrete kiosks that span the pedestrian walkways of the bridge.

Glenbow Archives

After nearly a century up on the bridge, and having undergone numerous restoration campaigns, the Lions were removed from the bridge in 1999 and replaced with cast replicas. At this time, one of the Lions was restored and installed in front of the entrance to Calgary City Hall, while the remaining three lions were placed in outdoor storage. In 2017, CSI assessed the lions as part of a larger assessment project carried out for the city’s public art collection. CSI was contracted by the City of Calgary to perform a conservation treatment on the original Northeast Centre Street Bridge Lion to prepare it for outdoor display at a public park overlooking the Centre Street Bridge and its original perch on its Northeast kiosk. For this work, CSI first carried out an initial condition assessment to develop a detailed treatment plan for the city, including assisting with structural reviews for its new design display.

The Northeast lion weighs a total of 13 tonnes which includes a segment of the bridge pier and the steel transport skid it still sits on. The figure measures roughly 10 ½ feet long by 4 ½ feet wide and 3 feet high at its back end and 7 feet high at its front end. The lion figure itself appears to have been cast in five separate sections and joined together with mortar at the seams. The separate cast sections of the lion were joined with a mortar of higher cement content than the concrete substrate of the cast portions, and the joins were not reinforced with steel armatures or pins. The perimeter of the plinth was also cast separately, although it is not fully clear in how many sections. It is possible that the perimeter of the plinth was cast in-situ after the body of the lion had been installed on the bridge, so that the edges of the plinth could be aligned flush with the edges of the pier.

The lion’s body and the central section of the plinth below the body are hollow. The concrete is reinforced with an internal interwoven rebar. A low-cement content base paste with a fine siliceous sand aggregate was used to make up the bulk to the lion figure. A higher cement content (stronger and more weather-resistant) facing mortar, approximately 1/16th of an inch thick was used for the external surface of the lion and for the joins between the cast sections.

Maurice Savoie Mural

The Savoie mural consists of 12 panels that hang on the west-facing concrete wall above the original entrance to the G. A. Hickman Education Building at Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland. Overall, the mural measures approximately 1,200 square feet, spanning two stories of the building. The mural’s panels are hung on galvanized iron shelf angles extending off of the concrete building wall. The panels depict an abstract composition of raised forms, embedded colored stone aggregate, inscribed textures and applied splashes of pigmented colours. There are also few slate roofing and terracotta tiles embedded in and projecting from the concrete. The composition extends throughout the panels and is not limited within each.

CSI

The work appears to have been cast face down within panelized molds. A negative form, with hollows where projections would be in the final work, was prepared from either sand or clay in the base of the mold. Stone aggregates, slate and terracotta elements, and the pigmented mortar would have been placed or broadcast in the mold directly on this sculptured bed. The slate and quartz pebbles would similarly have been partially buried in the mold so that they would project out after casting. These materials were partially encapsulated within the face of the initial layer of the concrete pour. This layer consists of a fine concrete mix without large aggregates, like a cementitious mortar. This mixture was placed to an approximate thickness of 1 ¼”. The un-coated ferrous reinforcing rods were placed at the back and partly embedded within this layer. The exposed face was then cross-hatched to increase adhesion, and a second layer of a concrete mix that includes both large and small aggregates and cement was poured atop it. Placement of this second layer must have occurred shortly after the initial pour as the backing is well bonded to the face layer.

‘Dinny’ the Dinosaur

‘Dinny’ is a 120-tonne concrete Brontosaurus that was sculpted for the Calgary Zoo in 1935. Dinny was the largest of a collection of 56 sculptures made for the zoo, which was then called the Calgary Zoo and Natural History Park. The sculpture is a hollow structure of cast concrete over reinforcing steel, measuring 40 feet tall and 118 feet long. While the sculpture does not reflect the correct anatomy of a Brontosaurus, it is possible that the sculptor, John Kanerva (1883-1974), based his design partially off local Albertan fossils found in the nearby Red Deer River valley. While most of the original sculptures from the park were dismantled and destroyed in the early 1980s when the zoo created a new Prehistoric Park of dinosaur sculptures on the other side of the river, the much beloved Brontosaurus was saved.

The dinosaur has been a draw for tourists since the time it was built and has become an icon of Calgary’s cultural fabric. The zoo landscape around the dinosaur has changed dramatically over the years; once surrounded by an open field, Dinny is now positioned closely adjacent to an animal pen, a busy roadway, and behind two small zoo facility buildings. A restoration campaign for the dinosaur would not only serve to bring the sculpture up to modern health and safety standards, it would also renew the iconic dinosaur’s presence in the zoo.

CSI

Condition Trends

The cementitious materials used to construct these artworks range in age from the 1910s, to the 1930s, to the 1960s. Nevertheless, similar conditions were observed across all three. Part of these similarities stem from the perceived durability of the materials and years of neglect as their size makes maintenance and conservation treatments challenging and expensive. For example, inappropriate or insufficient crack filling or lack of shelter coatings have presented serious issues for each of the artworks, as water infiltration has resulted in the corrosion of internal reinforcing steel leading to structural instability and rust-jacking of the concrete substrates, damage from freeze-thaw cycling, as well as carbonization and surface erosion of the concrete. Elements of inherent vice common to the concrete artworks, such as insufficient internal structural support, lack of concrete alkalinity, and shallow embedment of reinforcing steel were also found to be prominent issues throughout CSI’s assessments and treatments of these artworks.

Calgary Lion

Before CSI began treatment, major repairs to the lion had previously been completed, which included the insertion of staples across the joins of the head. CSI’s examination found that cracks smaller than 1/8” throughout the lion still required filling, and sounding revealed that a number of subsurface voids and delaminations were present. The locations of all hollow areas identified during sounding were recorded on high-contrast black and white images of the lion. It was noted that accessing some of these voids would require opening up previous repairs in order to inject repair materials into the adjacent hollow spaces to properly fill the deteriorated areas. During the re-excavation of previous repairs, it was found that some of the cracks in the plinth penetrated the full depth of the concrete.

Radiography and Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) was carried out on the lion by Gamma Tech Inspection Ltd. prior to conservation treatment. Internal reinforcing steel was found within the lion, but was found to be corroded to varying degrees, and no structural ties between the different cast sections were detected. Results showed that the internal steel may have functioned to support the weight of the concrete but never served as a structural form securing separately cast sections. Visual examination of exposed steel in the deteriorated base found that the extant reinforcing steel was found to be narrow in diameter (approximately ¼”), and highly corroded. The radiographic analysis also attempted to assess the thickness of the concrete of the lion’s body which estimated it to be between 8” – 10” thick in areas around the back and rear, and 6” – 8” thick in the collar area.

A heavy acrylic paint coating from a mid-1980s restoration still remained on the lion. The paint layer was cracked and compromised, but it was evident that it was still trapping moisture within the concrete. The use of an acrylic was likely intended to seal against water ingress while remaining “breathable”; however, the coating was extremely thick and impermeable and was trapping moisture within the concrete beneath it. Some damage, such as surface delamination, was attributed to the paint coating being lifted and blistered as moisture tried to escape, removing some of the surface detail with it.

Significant cracks in the plinth along possible casting seams indicated that the lion was structurally unstable. The concrete apron of the base beneath the plinth was highly deteriorated in parts, with significant losses, large scale erosion, and exposed and corroded reinforcing steel. It was identified that the deteriorated concrete apron would impede proper water drainage from the lion while on exterior display and would not provide sufficient structural support to the sculpture.

Maurice Savoie Mural

Prior to CSI’s assessment, the 12 panels of the mural were found to be structurally sound and well secured to the building. The mural’s surface, being a relatively porous cementitious mortar, is particularly susceptible to biological growth, fuelled by Newfoundland’s particularly wet climate. Biogrowth was present throughout the mural but varied in type and severity. Areas of the mural that have tended to retain more moisture, such as horizontal surfaces of the raised sculptural elements and the gaps between inset slate and quartz pebbles, were found to have more severe growth. Certain types of biogrowth were found to be harder than the decorative mortars, or in some cases the mortar of the mural itself. Under magnification, a black speckled type of biogrowth was found to have a bright yellow component, which risked staining the mural during cleaning.

The mural had suffered significant deterioration over the years, and the recent loss of large fragments had raised concerns for health and safety, since the mural is situated above the building’s main entrance. Two panels in particular had extremely large losses, one consisting of the lower 6 inches of a panel’s entire bottom edge and corners, and the other measuring roughly 3-foot square. Other smaller losses were scattered throughout the mural. For the majority of the losses, it was apparent that they were a result of rust jacking caused by the corrosion of the shallowly embedded reinforcing rebar. In addition to the losses, sub-surface voids were observed, which would have formed as a result of water ingress and freeze-thaw expansion. During the full sounding examination of the mural, some potential delamination was identified between the mortar layer and the backing concrete, particularly towards the exterior edge of the bottom proper right corner panel. This likely formed due to erosion as moisture penetrated between these materials, entering in along the exposed seam on the edge of the mural.

Surface cracking was observed throughout the mural, primarily on raised sculptural elements. These raised elements are more textured and tend to collect water, particularly those with horizontal surfaces. The water draining from these surfaces has caused general erosion as well as the formation of grooves and cracks. Cracking was also often associated with the grooves in the mortar created from the original casting techniques. Overall, cracks did not pose structural issues, and did not penetrate deeper than 1/16” – 3/16”. However, cracks allowed for further water ingress into the mural, threatening the internal rebar. Biogrowth was also particularly prominent in crack recesses due to excess water retention.

The splashes of red and green pigmented mortar throughout the surface of the mural suffered from varying degrees of loss. In some areas of the mural, the decorative pigmented mortar itself has fully detached. In general, the pigments have leached gradually from the decorative pigmented mortar, leaving red and green staining on the surface of the mural. This is thought to be a result of the decorative mortars being highly saturated with pigment in order to achieve the bright vivid green and red colours.

In addition to natural and inherent forms of deterioration and damage, numerous holes had been drilled into the lower sections during the installation of different lighting fixtures over the years, and numerous ferrous screws and bolts were found embedded throughout the mural mortar.

‘Dinny’ the Dinosaur

CSI is scheduled to carry out a detailed assessment of the dinosaur sculpture in May 2018, in conjunction with a review by a local engineering firm. Dinny’s primary issues are related to health and safety concerns. The neck is structurally compromised due to the nature of the sculpture’s design: there is no internal reinforcement between the neck and the body. A combination of concrete degradation and rust-jacking from the corrosion of internal rebar has caused fragments of the substrate to detach in the past, a problem which poses a large risk to public safety. Furthermore, it is believed that several layers of paint on the dinosaur are lead-based, and the concrete substrate itself may be reinforced with asbestos, which was a method used during the period of ‘Dinny’s’ creation. If these hazardous materials are present, they will pose serious containment issues during treatment.

A large hole in the underside of the belly was cut during a 2008 engineering review to facilitate an internal review of the structure. This hole, however, remains fully open, exposing the interior to water, snow, animals, and debris. (It also shed light on a long-standing local rumor that a Model T was inside Dinny’s belly.) A network of variously sized cracks and small losses throughout the sculpture has led to increased water infiltration, and the subsequent corrosion of the reinforcing steel. Salts have also been observed to be leaching from the concrete matrix. The dinosaur has undergone numerous re-painting schemes, and as a result its original painted appearance has been dramatically altered. The existing paint has started to crack and peel-off in certain locations.

CSI

CSI’s assessment will involve a full sounding of the sculpture to identify and document subsurface voids and delamination. CSI will carry out its assessment simultaneously to an engineering review, which will assist in developing the plan for the insertion of an internal reinforcing armature into the dinosaur’s neck. Additional Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) will be performed during the engineering review to analyze the nature and condition of the internal rebar. CSI will assess the site of the dinosaur to identify any hazards associated with its location and will work with the engineers to evaluate any supporting substructure (such as a concrete pad or piles) and look for any settlement problems. CSI will take samples that will be tested for layers of lead paint and asbestos in the concrete. In addition, cross-sectional paint samples will be taken from strategic locations throughout the dinosaur and analyzed to supplement historical records used to determine original paint schemes.

Treatment Strategies: Calgary Lion

In order to render the concrete breathable again and prevent further moisture from being trapped within it, as well as to facilitate consolidation of the concrete, it was decided to remove the aged acrylic coating that had been applied during a 1980s restoration. Because the surface layer of concrete was already eroded in areas, it was felt that abrasive aggregate cleaning would be too aggressive and would likely result in the removal of too much surface detail. CO2 (dry ice) cleaning was selected as an alternative. In this method, dry ice pellets are delivered through a unit that accelerates the CO2 through a pressurized air stream, dispersing the CO2 in small particles through an application wand onto the surface. The surface coating is flash frozen, and the thermal shock creates shear stresses within the coating that cause it to dislodge. This method is generally highly effective while posing minimal risk to the substrate. Unlike abrasives, it does not produce secondary debris that requires extraction and subsequent cleaning of the surface. The CO2 cleaning offered a high degree of control, and it was possible to remove the coating in a gradual, gentle process.

CSI

Once the coating was removed, the concrete was consolidated using a ProsocoTM ethyl silicate system. This system works by permeating the porous surface and chemically binding with the concrete, increasing its stability and cohesive strength and protecting against further erosion and weathering. The consolidants were applied by hand pump sprayers, carefully following manufacturer instructions. The system first involves the application of ProSoCo Conservare HCT which is designed to strengthen deteriorated concrete or stone by forming a hydroxylated conversion layer on carbonate minerals in the substrate. This was followed by the application of an HCT Finishing Rinse product that completes the chemical formation of the conversion layer. Once all of the repair work on the lion was completed, ProSoCo Conservare OH100 was applied, which consolidates by replacing the concrete’s lost binding materials with ethyl silicate which binds to the silica components of the concrete.

Open cracks and areas that had been identified during examination to have subsurface voids and cracking, were repaired. Any loose or failed repairs from previous treatments were removed, and some previous repairs were removed to access adjacent or underlying voids. Attempts were made to fill all cracks and voids to their full depth wherever possible. Deep cracks on the plinth were first filled with epoxy to penetrate deep and fill narrow recesses. The product was applied gradually over several hours (and in some cases, days), to allow for the epoxy to migrate and settle into the full depths of the cracks. After the epoxy was set, the wider upper portions of the cracks were filled with VoidspanTM PHLc70 injectable lime grout, pigmented to match the surrounding concrete. The Voidspan lime-based grout was chosen because, while it is highly durable, its breathability, flexibility and softness make it more compatible with the 100-year old, deteriorated concrete than traditional cement-based or polymer modified mortars.

CSI

The City’s intention was to preserve the lion as a “ruin”; therefore, a semi-transparent final coating option was selected. This allowed for the repairs and the texture of the historic concrete to remain visible, while still providing sufficient coverage to adequately protect the concrete from its environment. Keim’s Design-Lasur, a pigmented sol-silicate based coating, was mixed with the Keim Design-Fixativ to achieve a semi-transparent finish. This final coating will provide protection from water and weathering by filling and bridging small pores yet will remain transparent enough to allow the underlying concrete to show through.While the lion has not yet been transported to its new location, CSI provided recommendations for future maintenance. The maintenance procedures that were recommended included regular low-pressure cleaning and guidelines for graffiti removal, annual monitoring for cracks and water infiltration points, and a tentative timeline for the next full-scale coating renewal to ensure the concrete remains well-protected from the elements.

Maurice Savoie Mural

The mural was cleaned overall to remove biological growth and biogrowth staining. D/2 Biological SolutionTM was used to help remove live biogrowth and biogrowth staining. The solution was applied to the mural with a hand pump sprayer and left to activate on the surface for several minutes before scrubbing with soft brushes. Once scrubbed, the surface was rinsed with warm water applied through a pressure washer. The solution does not leave a residue on the surface, and is biodegradable making it safe to use around plants. For particularly tenacious biogrowth, considerable amounts of scrubbing and multiple rounds of cleaning was required to remove it, which largely extended the length of the cleaning process. Care was taken not to disturb or dislodge any pigmented mortar or leach pigment during cleaning. In some cases, biogrowth was much stronger and harder than the pigmented mortar, or even than the cementitious mortar of the mural, and had to be removed using wooden skewers and stainless steel dental tools.

CSI

Cracks were cleaned out and filled with VoidspanTM PHLc70 injectable lime grout, pigmented to match different areas of the mural. Areas that required repairs and fills were cut-back and cleaned to properly receive the selected repair mortar. Any exposed rebar was cleaned with micro abrasives to remove corrosion products and coated with Cortec Corrverter® Rust Primer, an acrylic coating with a multi-metal corrosion inhibitor. For larger repairs, new stainless steel pins and rods were added at a depth sufficient to ensure proper coverage by the repair material but were kept isolated from the original ferrous rebar. Repairs were completed using JAHN M70 S1-LS Natural Stone Repair Mortar, a fully mineral base, 1-component mortar developed for the restoration of softer stone and masonry. In addition to its moisture, frost, and salt resistance, this mortar was particularly appropriate due to its similar physical properties (strength, texture, colour) to the cementitious mortar of the mural. A local aggregate was used, and mock-ups were carried out to achieve a good match for the repairs. Where necessary, crack repairs or patches were toned with a mixture of dry-pigments suspended in Keim’s Deisgn Fixativ, a clear sol silicate mineral coating.

CSI

All of the aged sealant was removed from the joints between the panels prior to the start of the treatment. Once all the repairs were complete, Tremco’s Dynomic FC sealant, a high-performance, fast-curing, single-component, hybrid sealant, was applied to seal all of the panel joins in order to reduce water ingress between and behind the panels. Repairs and caulk were allowed to cure for a period of 4 weeks. Keim’s Silan-100 alkylalkoxysilane water repellent coating was applied to the entirety of the mural to reduce future water infiltration and to mitigate the formation of biogrowth. CSI also provided direction for the addition of new roof flashing to over-hang the top of the mural. This will help prevent water run-off from the roof from infiltrating in and around the mural’s panels.

CSI made clear recommendations to the client that the continued life of the mural will depend on regular renewal of its water repellent coating, and annual cleaning using a biocidal detergent. Furthermore, it was stressed that a regular monitoring program would help to identify any future issues before they become critical.

‘Dinny’ the Dinosaur

Addressing the health and safety concerns will be the highest priority of the treatment interventions. This will include the insertion of the internal reinforcing armature in the neck, the removal of hazardous lead paint and asbestos, and the stabilization and consolidation of any loose or detached substrate. Repairing cracks and losses and replacing the accumulated layers of paint with a breathable mineral-based shelter coating would serve to reduce the entrapment of internal moisture and slow the freeze-thaw deterioration of the concrete. A re-painting scheme will follow historical research and documentation to re-create the dinosaur’s original painted appearance.

The biggest challenges will be performing this work on such a large object located in the middle of a very public space. The treatment will coincide with a particularly busy time for the zoo, as it will be hosting a famed pair of Pandas loaned to Canada from China. If hazardous materials such as lead paint or asbestos are present, stringent and sophisticated containment measures will be required to protect workers, the visitors, and the zoo animals from airborne and settling hazardous debris. CSI will work directly with the zoo staff to promote and disseminate information about the treatments to the public, as this will be a high-profile project. Once all treatment work is complete, CSI will work with the zoo staff to develop a feasible maintenance plan for the sculpture to help ensure that ‘Dinny’ can continue to be enjoyed by its fans for years to come.

Conclusion

Despite the variation in size and scope of the three artworks discussed in this paper, each of them demonstrates similar challenges associated with aged historic concrete. Issues of water entrapment, freeze-thaw cycling, and corrosion of reinforcing steel are particularly destructive to concrete substrates in the variable and at times harsh climates of Calgary and St. John’s. The long-term preservation of this “concrete menagerie” is dependent upon resources for regular monitoring and maintenance in order to mitigate against moisture infiltration. The treatment work carried out by CSI on the Calgary Lion and the Maurice Savoie mural, and the treatment interventions that will be taken on Calgary’s ‘Dinny’ the Dinosaur, will hopefully establish a new and stable foundation that will stimulate improved conservation maintenance and preservation planning for these artworks. It is CSI’s hope that the stewards of these pieces will be able to capitalize from their community’s love and attachment for these artworks in order to secure the resources necessary for their long-term care.

Symposium

You can read other articles from the proceedings of Are We There Yet? Preserving Roadside Architecture and Attractions, April 10-12, 2018, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Or explore other content from the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training (NCPTT).