Last updated: April 12, 2021

Article

Conservation Efforts in the Lower Farmington and Salmon Brook Watershed - Upcoming Biodiversity Surveys this Spring and Summer

Two biodiversity surveys will be conducted along the Lower Farmington River this spring and summer with hopes of finding, and further protecting, threatened and endangered species.

by Cassidy Quistorff, NPS Communications Fellow

The Lower Farmington and Salmon Brook Rivers have outstandingly remarkable biodiversity. The watershed has a mosaic of landcover types, including wetland systems, large forested tracts, early and late successional uplands, mixed development and agriculture, which provide habitats for a diverse assemblage of species. Several surveys illustrate the diversity of birds in the watershed with over 2000 individuals recorded comprised of 105 different species.

Perhaps one of the most exciting results from watershed surveys was the 2006 mussel survey which showed the Farmington River containing all 12 mussel species native to Southern New England. The Farmington supports higher species richness than any other river in Connecticut or New England (outside of Vermont’s Champlain Valley), and the lower Farmington River is home to the federally endangered dwarf wedgemussel (Alasmidonta heterodon). All of Connecticut’s state-listed mussel species are found within the Farmington River, and the dwarf wedgemussel (Alasmidonta heterodon) occurs in an approximately 12-mile stretch of the lower Farmington River. The broad range of habitats from headwaters to tidally influenced waters support this biodiversity.

For Ethan Nedeau, a freshwater mussel biologist, that makes the Farmington one of his favorite rivers. “It’s a special river in a lot of ways, but the standout thing is that it does support the dwarf wedgemussel population which is a federally endangered species. This is the only river in the Connecticut River Watershed that supports every single species that is native to the watershed. Other rivers may have 5 or 6 species, but the Farmington has all twelve. No other river in the watershed can make that claim.”

For the past 25 years, Ethan has done work all across New England focusing on mussel surveys. Back in 2005, 2006, and 2008, Ethan surveyed the Lower Farmington River and Salmon Brook and will be returning this year. “We did the last survey 13-16 years ago, and there are probably individual mussels in the Farmington river that we could find again. Maybe not the dwarf wedgemussel, as that [species] has a relatively short lifespan compared to others, about 10-15 years… Freshwater mussels as a whole are very long lived, some in New England could be upwards of 50-70 years old,” Ethan explained.

Freshwater mussels are unique in that they require fish to reproduce. Mussel larvae are obligate fish parasites; adult female mussels release larvae into the water where they must find and attach to a fish’s fins or gills. While attached, they can be carried long distances depending on how fast and far the fish swims. They’ll remain attached for weeks to months until they drop off and begin their free-living existence in the riverbed or lakebed. Different mussel species require different fish species to reproduce…not any fish will do! For the dwarf wedgemussel, its primary host fish is a tessellated darter (Etheostoma olmstedi), a small bottom-dwelling fish that is common in the lower Farmington River. Other mussel species in the Farmington River rely on fish species such as brook trout, American shad, American eel, white sucker, and a variety of small minnows such as blacknose dace and common shiner. The Farmington River supports a very diverse fish assemblage, and this helps to sustain such a diverse mussel assemblage.

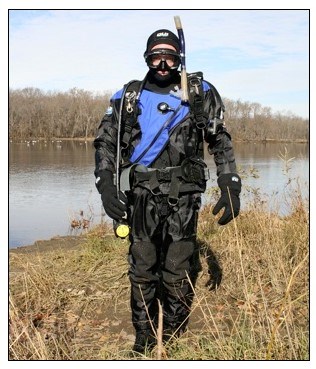

This year, Ethan will be working to resurvey the Wild and Scenic sections of lower 35 miles of the Farmington River from Lower Collinsville Dam to the Connecticut River (~30 sites) and the lower Salmon Brook (~3 sites) to update species maps, reassess mussel habitat, and help to identify threats and conservation opportunities within the river. “Our previous work wasn’t quantitative, so we don’t have a rigorous baseline to see if there’s been a significant change in populations, but we can at least compare catch rates from then to now... Our hope is to revisit all the areas where we’ve ever found the dwarf wedgemussel and see if we can find it again, or spend enough time at each site to find as many as we can. We’ll record the basic data on their lengths, conditions of the shells, what types of habitats they are in, and identify any obvious threats at each of those sites.”

Ethan also spends his time communicating mussel science to the public through publications, watershed talks, and even a book on the mussels in the Connecticut River watershed.

“I think people should know about their importance to ecosystems as filter feeders and a source of food for native mammals and fish... the fact that a lot of them are rare, through no fault of their own, but because we’ve done things that fragment and pollute rivers, and alter native fish communities,” Ethan said.

Dennis Quinn is also passionate about oft-overlooked species in the Lower Farmington River Watershed, reptiles and amphibians. Dennis curates the CTHerpetology website, A Photographic Atlas for the Identification of Connecticut's Amphibians and Reptiles. Dennis will also be continuing his herpetological inventory surveys this spring and summer within the watershed.

“Specifically, we’ll be looking at the diversity of species and try to figure out management actions that can promote species conservation and guide recreational activities so that they don’t have a big impact,” Dennis explained.

“Development is a pretty obvious impact, but there are also impacts from passive recreation that can be easily avoided when you have a better understanding of the species that are using the watershed and their critical habitats. Then [we can be] better at avoiding those critical habitats especially since some would only require seasonal restrictions. Nesting areas for turtles are very important to identify so that during the spring and early summer months you can reduce and avoid traffic in those areas,” Dennis explained. Dennis promotes best management practices that avoid detrimental ecological consequences, like scaring female turtles off nests, while promoting sustainable land use and recreation along the river. “From my perspective, if the public cannot go out and enjoy the resources, there is no incentive for them to protect and promote the resource. So you have to keep that alive, you have to keep it strong. But it is a balance,” Dennis continues.

Surveys such as these can help guide local conversations about river management by providing science-based information to inform decision making processes in your rivers and watershed. These surveys can have lasting benefits by providing baseline data on biodiversity, informing how to protect and enhance species critical habitats, and promoting excitement about the natural resources of your waterways.

“It’s important to really understand the ecosystem as a whole and understand what you are actually protecting in the ecosystem. The more informed you are, the more effectively science becomes the driver of protection and designation of sensitive habitat areas,” Dennis stated.

“Understanding regionally significant resources helps guide where limited resources and efforts are best focused in the state. I think a regional approach to conservation is really important. Once you understand the regional diversity, you can really focus your [conservation] efforts to have the largest impact for species conservation.”

If you are interested in increasing or maintaining the biodiversity along your waterway Dennis and Ethan have some suggestions.

-

Learn more about local biodiversity

-

Once you know more, spread a love for these charismatic species

-

Support land use ordinances that encourage best management practices and thoughtful land use development

-

Report species you find to the CT DEEP through their Natural Diversity Database Special Animal Reporting Form

-

Provide habitat for native species on your lands, and think about how important habitat connections are for the wildlife that rely on them

-

There are many resources available to learn more about the conservation of Connecticut species.

Special thanks to Dennis Quinn and Ethan Nedeau for their time and continued conservation efforts and stewardship of these species along these special rivers.