Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 106: Color, Pigments, and the work of Hélio Oiticica

B. Epley

Hélio Oiticica

Catherine Cooper: I’m here at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston with Cory Rogge.

Cory Rogge: Hello.

Catherine Cooper: And today I wanted to ask you about the Hélio Oiticica collection that you have here that you’ve been working with.

Cory Rogge: So we have an amazing Latin American arts collection at the MFAH. And in the early 2000s our Latin American arts curator, Mari Carmen Ramírez, reached out to the Oiticica family because she was interested in doing a show on Hélio Oiticica, who had died in 1980. He was born in 1937.

Oiticica was a Brazilian artist and he kind of came of artistic age at the very end of the concrete art movement in Brazil. And here, concrete doesn’t mean like concrete sidewalks. Concrete means constructivist, more like Mondrian. So very geometrical, very rigid paintings.

And Oiticica was really interested in art, but he quickly became bored with the two-dimensional aspect of things and launched his art into three dimensions, all the while being very interested in color.

© César and Claudio Oiticica

Oiticica Family

And Oiticica’s father was a scientist, an engineer, and an entomologist and a mathematician, and Oiticica actually worked in the museum where his father worked. And so he kind of, despite being an artist, had a scholarly or a scientific approach to what he was doing. And he kept amazing journals and he kept his paints.

And so as part of this exhibition, our Mari Carmen and our then head of conservation went down to Brazil, brought the artworks back for treatment, but also brought all of the extant studio materials that were still with Oiticica’s family.

And at that point there wasn’t a scientist here in Houston. So the paint sat—on a cart—for years. Until I showed up and got asked to look at them as part of a Getty project on concrete art in Los Angeles. And we were interested in them because number one, they’re a record of what he used, which is interesting of itself.

© César and Claudio Oiticica

Recreating Artwork Lost in Rio Fire

Also, unfortunately a lot of his extant artwork burned in a fire in Rio. And so these paints are the only records we have of what was on his art. And they give us insight into what the colors of his art should be. And then Oiticica also kept journals: he kept diagrams for his artwork, he kept recipes of what the color mixtures were that he was using on a given piece of art.

They weren’t always very accurate in that he measured out his amounts in spoons. So we had a soup spoon and a teaspoon and a coffee spoon. And in his notebook he’ll say, “This color of yellow is made by mixing one soup spoon of this with one coffee spoon of this and a teaspoon or two of that.” So we don’t know the volumes that were involved really, but we can guesstimate.

So now what we’re interested in doing is taking the paints, figuring out what the pigments are, and then figuring out what the binding media is and then seeing how that relates to what his recipes were because he wasn’t mixing his paints by taking pigment and mixing it with oil.

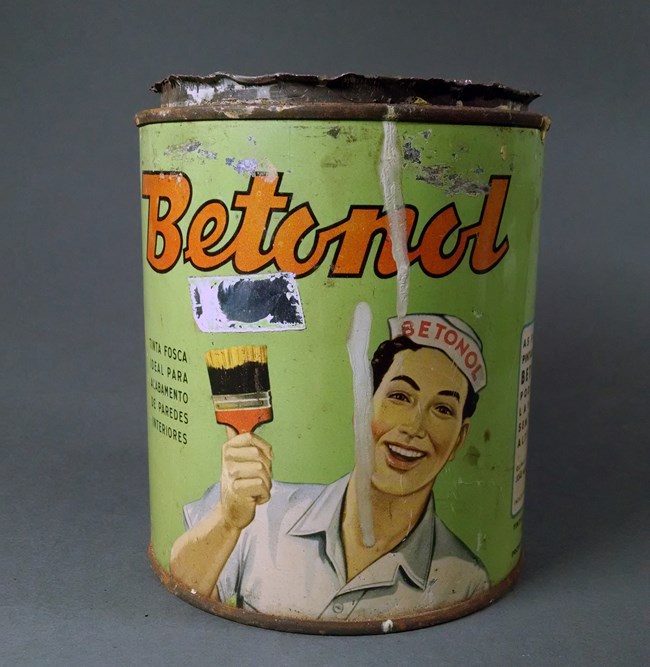

He was mixing his colors by mixing different amounts of other paints and we don’t always know what was in the other paints and he’ll say, “I mixed a soup spoon of this brand of paint’s Vermilion red with this teaspoon of an orange paint with this.” We won’t know what the Vermilion really is, so we’re trying to pick that out as well. So long story short, those are the paint collections and that’s how they came to live in Houston.

Documentation, Materials and Paints

Catherine Cooper: Have you been able to see the convergence of his documentation of a work with one of the few that still exist with the artists’ paints that you have?

© César and Claudio Oiticica

Cory Rogge: Wow, complicated question. So he went through a bunch of different series as he broke out of strictly two dimensional art, and the first series to really do that he called Inventions and these were square paintings that hung off from the wall. They were offset so they leapt out into space just a little bit.

And we have four paints related to the Invention series and these are all bright, brilliant reds in tone.

The next series we get into are the Spatial Reliefs and the Nuclei and here he backs away from red, he starts going into the yellow colors and then from there he jumps off entirely into three dimensional objects that you can handle or that you can wear or that you can walk into or around and manipulate.

And so he really, at least color wise, he makes a break from the inventions which are largely bright red into these yellow-oranges that he tends to favor later on. In terms of pigments, I guess we find differences from what he wrote and what he used and that he would say things in his journals like “This pigment isn’t very stable, this other yellow pigment would be better”, but in fact we find the one that he thinks is less stable in a lot of his artwork so he doesn’t always practice what he preaches.

And then in terms of binding media, most of what we have are oil paints. He manipulates them a little bit. He mixes in some commercial paints that are alkyds and faster drying than oils, but he’s not being like other Brazilian artists at the time, like Lygia Clark, who were using really modern paints like nitrocellulose automobile lacquers.

Even though he’s being very nontraditional in how he uses them and the objects that he’s making, he’s still using really traditional materials.

Catherine Cooper: Where do you hope to take this research or is it mostly completed for this past exhibit or is it hopefully going to inform future conservation or future work with the family?

Cory Rogge: I’m slowly in the process of writing this all up, but there are 139 different studio material things that came. Most of them are paints, but we have some powdered pigments and some varnishes and some media that he used.

And right now I’m in the process of trying to correlate all of what a given paint has in it with what his journal articles might say. And then what we’ve learned is that his objects are sometimes more complex than he indicated in his journals. So for an object he might say, “Oh, I made three paints for it, or four paints for it.” But in our collection we have 21 so we know that he layered his paints.

Are these iterations, did he manipulate the color, but change the color ever so slightly—evolve the color as he went along?

Were these paints really all on a given object?

We don’t know, but because so many of his artworks burned and we have the journals, the family has been reproducing them. And so this information we have will inform them in those reproductions because they’ll be able to better understand that his paints and his objects were not a single flat tone of color. The surface color was influenced by the layers below and so they’re much more vibrant an object than the reproductions are.

© César and Claudio Oiticica

Conservation Challenges

Catherine Cooper: Does the depth and complexity of the pigments relate to conservation problems as these objects age?

Cory Rogge: So we have issues with, with our object, the fact that he has tried to make plywood act like paper. Plywood doesn’t bend like paper, so you can’t get those creases. So he had to force the wood into bends and turns that it doesn’t want to make, and so some of the seams are opening up and that’s causing paint loss. He had actually intended to make more of these kinds of objects and gave them up because they were so very hard to construct.

In terms of the stability of his materials, he actually used really stable materials for the most part. So we’re not having too many issues with his objects fading for instance, as far as we can tell.

Because so many of them lived in environments in Brazil that had relatively poor climate control, there have been issues caused by expansion and contraction with the wood, which can cause paint loss. And then also just dirt in the environment. Museums filter their air to keep dust and grime and pollutions out and other institutions and places don’t have that benefit.

What should people know about Hélio Oiticica?

Catherine Cooper: What about Oiticica’s art—for people who are unfamiliar with it—what should people know?

Cory Rogge: He was one of the most inventive artists out there, and he really kind of revolutionized what was thought of as art. For centuries art was on paper, art was a painting, it was hung on a wall. And he thought that color was an object and he wanted to make these color objects, he called them, that were interactive, that allow people to see color and experience it in a way that nobody else had. And so we have American artists like John Cage or Robert Rauschenberg who are doing art that’s breaking the boundaries of moving beyond painting into interactive exhibits, into interactive occurrences, happenings, and Oiticica was doing that at the same time.

And so he’s really, he’s changed what art is. He made a series of objects called parangolés, or capes, and they were meant to be worn and danced around the streets and in Samba dances. And so he’s doing performance art, right, and making objects for that.

Catherine Cooper: For any of those performance art pieces still existing, are they being treated in performance or are they stationary now?

Cory Rogge: They are stationary. But for the exhibit here, the foundation and family permitted reproduction ones to be made that the public were allowed to wear and to dance with the way that Oiticica would have wanted.

Conservation and Integrity of the Art

Catherine Cooper: The intersection of the integrity of these objects and conservation of them is always an interesting question when they’re in use.

Cory Rogge: Yes. And he made a series, another series of objects called bólides which translates into firecracker and here he wanted people to interact with color in the form of pigment.

And so there are boxes that can be opened that have pigments in them or there are jars that have pigments in them. You can put your hands in them and stir the pigment about and sift it like grains of sand. And in a museum environment we can’t let people do that because it would go everywhere and some of the pigments aren’t necessarily good for your health to be doing that. So we do walk a line—we can explain how they’re meant to be used and there are photographs of him using it. But we chose in that case not to ask the family if they can be reproduced for the public to use.

It’s really been an interesting project because it’s made me learn a lot about Brazilian paints that I didn’t know and the paint industry in Brazil. Oiticica was kind of transnational in that he also lived in the U.S at two different points, and he lived in London and he wrote letters to people.

He and Lygia Clark had an extensive correspondence, so you could go back through and get a real sense of him as a person and his real philosophical take on what he was doing and talking about the psychology of stuff. And then you have his wonderful journals and then you get to learn a little bit of Portuguese for reading them. The more you read about it, the more interesting he really becomes as a person and unfortunately the conversation is one sided, right? He’s talking to me from the past. I can’t-

Catherine Cooper: Ask him.

Cory Rogge: Exactly, but I think he would have been a really interesting person to have been a friend.

Catherine Cooper: Thank you so much for talking with us today.

Cory Rogge: It’s been a pleasure.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.