Last updated: August 4, 2022

Article

Coastal Lagoons Resource Brief for the Arctic Network

Kevin Fraley, Michael Lunde, Martin Robards, Tahzay Jones, and Alex Whiting

Courtesy of Beatrice Smith, Wildlife Conservation Society

The status of coastal lagoons in the Arctic Network

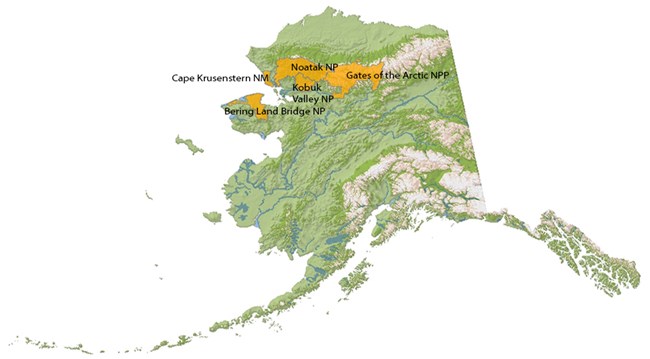

Hundreds of miles from Alaska’s road system lies the array of coastal lagoons of Cape Krusenstern National Monument – including Aukulak, Krusenstern, Tasaychek, Kotlik, Imik, Ipiavik, and Port – that shape the shoreline landscape from Kotzebue northward towards Point Hope, Alaska. Southwest of Kotzebue, Bering Land Bridge National Preserve contains additional lagoons– Kupik, Arctic, and Ikpek. These shallow water bodies are seasonally productive ecosystems that contain critically important habitat for migratory fish and waterfowl. In addition, lagoons support high abundance of prey fish and invertebrates which provide a food source for predatory fish and wildlife. Many of the migratory species, like sheefish and sandhill cranes, are important subsistence species for Iñupiat and other rural residents of the region. Most lagoons connect to the Chukchi Sea during periods of high freshwater runoff, or during coastal storms that facilitate breaching of the gravel berms that separate them from saltwater. Others remain constantly connected to the ocean, while some may not connect every year. Despite the remote, pristine nature of these lagoons, changing seasons as a result of climate change, coastal erosion, and human development in the Arctic may result in consequences to lagoon ecosystems and the people who utilize them.Changes in the layout and ecology of the lagoons of Cape Krusenstern National Monument and Bering Land Bridge National Preserve have been observed and documented throughout the region since the 1980s, for example, in the journals of Bob Uhl, who maintained a subsistence lifestyle at Sissualik with his wife Carrie for more than five decades. Changing seasonal timing, freshwater runoff, and storm frequency can affect lagoon connectivity with the marine environment. A lack of breaching events stops the movement of fish in and out of lagoons and severe winters in which lagoons freeze nearly completely to the bottom result in mortality for trapped fish, reduced invertebrate abundance, and other alterations to the food web.

Courtesy of Kevin Fraley, Wildlife Conservation Society

USFWS/Susan Georgette

Why lagoons are important

Lagoons are important landscape features because their varied size, depth, connectivity to the ocean, and chemistry creates a mosaic of aquatic and terrestrial habitats utilized by a diverse group of organisms. These locations are home to healthy populations of furbearers, waterbirds, and fish, resulting in a plethora of subsistence fishing and hunting or trapping opportunities for Iñupiat residents who rely on wild-harvested resources for food security. Lagoon-caught fish such as Dolly Varden, sheefish, chum salmon, and least cisco are netted, dried or smoked, and eaten year-round. Animal hides can be obtained near the lagoons and are commonly used for hand-making garments and household items. Waterfowl and gull eggs are highly-valued food items that can also be harvested at these locations. Lagoons have been at the center of subsistence and cultural activities of Iñupiat for thousands of years, as evidenced by the important archeological sites present in the beach ridges near Krusenstern Lagoon.Besides subsistence and cultural importance for Iñupiat, the Arctic National Parklands that include the lagoons are highly valued as beautiful, remote places to visit by birders, wildlife viewers, outdoor recreationists, and anglers worldwide.A combination of all these properties – subsistence importance, ecological uniqueness, value for tourism, and remoteness from the outside world – make the coastal lagoons of Cape Krusenstern National Monument and Bering Land Bridge National Preserve important resources to tribal organizations, National Park Service, and the scientific community who strive to understand and protect these ecosystems.

NPS/ Courtesy of Mike Lunde, Wildlife Conservation Society

How we monitor lagoons

Beginning in 2012, NPS, Wildlife Conservation Society, and the Native Village of Kotzebue Environmental Program have partnered to study coastal lagoons of Cape Krusenstern National Monument and Bering Land Bridge National Preserve. Monitoring occurs every year at three core lagoons: Aukulak, Krusenstern, and Kotlik within Cape Krusenstern National Monument. Other lagoons including those in Bering Land Bridge National Preserve are sampled periodically, when logistically feasible. Two visits to the core lagoons occur each year, one in June/early July and one in August, to capture inter-annual and seasonal variability in fish diversity and abundance and water chemistry. Additionally, since 2016, lagoon break-up, connectivity to the ocean, and ice up has been recorded through use of Sentinel-2 daily-weekly resolution satellite imagery.During monitoring fieldwork, three sites are sampled at each lagoon for fish abundance and species diversity (lagoon outlet, freshwater input, and marine edge), while water chemistry is measured at 7 locations (fish sampling sites plus the geographic center of the lagoon and three locations randomly spaced). This approach ensures that sampling across seasons and years is consistent and comparable, so changes and patterns can be identified. For fish sampling, WCS deploys tangle nets for six one-hour sets at each site, conducts two shoreline beach seines, and at the outlet site only, three two-hour fyke net sets. Net set times are adjusted based on the number of fish caught, and standardized to “catch-per-unit-effort” so data is comparable. Rod-and-reel angling is also employed to capture large-bodied, net-shy fish for assessing species diversity. Water chemistry parameters are measured with a special high-tech instrument and include temperature, salinity, turbidity, algal content, pH, and conductivity.

Lagoon monitoring was paused in 2019 and 2020 due to logistical and COVID-19 concerns, but resumed in 2021.

Seasonal connectivity of Kotlik Lagoon with the Chukchi Sea

Left image

This image taken in June shows Kotlik Lagoon open to the ocean.

Credit: Sentinel-2 satellite images (2021)

Right image

This image taken in August shows Kotlik Lagoon closed to the ocean.

Credit: Sentinel-2 satellite images (2021)

What kinds of fish inhabit lagoons?

Fish are among the most prominent organisms that occupy coastal lagoons, and are an important subsistence resource. Because of this, we focus on fish for much of the lagoon monitoring and study efforts. Coastal lagoons represent important habitat for multiple types of fish – freshwater resident species like Arctic grayling and Alaska blackfish, anadromous species like least cisco and sheefish, and marine taxa like saffron cod (“tomcod”) and starry flounder – that utilize these environments for multiple reasons. Fish of all sizes and ages swim in and out of the lagoons in search of food, shelter, places to spawn, and as migratory corridors into rivers and lakes. Other common species of fish found in the lagoons of Cape Krusenstern National Monument and Bering Land Bridge National Preserve include humpback whitefish, least cisco, Pacific herring, Dolly Varden (known locally as “trout”), threespine and ninespine stickleback, pond smelt, and marine sculpins. While spring, summer, and autumn are good months for fish to occupy lagoons for feeding, rearing, or reproduction, most exit the lagoons during the winter because the main bodies of the lagoons freeze almost completely solid. Unless they become trapped in a lagoon (and likely perish), fish are thought to overwinter in deeper, flowing freshwater rivers, lakes, or in the ocean where there is more liquid water and dissolved oxygen to support survival.

Courtesy of Kevin Fraley, Wildlife Conservation Society

What do we still want to learn about lagoons?

Despite the knowledge we have gained on how these lagoons function, there remains many unanswered questions in relation to a rapidly changing climate and possible industrial development in the Chukchi Sea region. The marine and terrestrial landscape of Alaska’s Northwest Arctic is a highly dynamic environment, and it is unknown how climate change and human development may impact the physical landscape, ecology, and geographic distribution of fish and wildlife. Because lagoons are such prominent features along the Alaskan Arctic coastline, there is interest among the scientific community, tribal organizations, and the public in learning more about these ecosystems. Given this, WCS, NPS, and the Native Village of Kotzebue Environmental Program plan to explore the following research questions in the future, through co-produced research protocols and activities:

- How frequently do anadromous fish like sheefish, humpback whitefish, least cisco, broad whitefish, and Bering cisco utilize lagoon habitats? Where are these fish coming from and going to? A sheefish tagging and tracking study and a whitefish otolith microchemistry study are currently underway to begin to answer these questions. Sheefish captured in coastal habitats will be affixed with a GPS pop-up tag by WCS to record their movements and behaviors along the coast near Kotzebue Sound. Otoliths (earbones) from 60 whitefish of several species (collected in lagoons) are being chemically analyzed at the University of Alaska Fairbanks to determine how often the fish moved between freshwater, brackish, and marine habitats throughout the course of their life.

- Can fish successfully overwinter in lagoons or their freshwater sources? If so, which fish species and which lagoons and tributaries? Most lagoons are shallow and freeze to the bottom, demonstrating complete winterkill and lack of fish when a connection to the marine environment does not occur (Aukulak Lagoon). However, some lagoons are connected to larger freshwater rivers that contain flowing water through the winter, as evidenced by the presence of freshwater resident fish like Arctic grayling (Kotlik and Krusentern Lagoons).

- How abundant are Arctic grayling in coastal lagoons and their associated freshwater systems, and what kind of movements do these grayling undertake? WCS has captured grayling near freshwater input areas in Kotlik and Krusenstern Lagoons, but grayling are occasionally caught in the brackish main body of the lagoons and likely undertake movements throughout the lagoon systems to feed and spawn. However, nothing is known about the abundance or movements of these important sport fishing and subsistence species in these environments.

- Do lagoons fish contain harmful contaminants that may be of concern to subsistence harvesters? Dolly Varden, saffron cod, flounder, and whitefish of several species were sampled and analyzed for PFAS and mercury concentrations in muscle tissue. Very low levels were found and the findings are currently being written up for peer-reviewed publication.

- Are break-up, lagoon connectivity duration, and ice-up dates changing for Southern Chukchi Sea coastal lagoons? What are the trends and implications for fish and subsistence harvesters? WCS is recording these dates from 2016 onwards through examination of Sentinel-2 satellite imagery, and analysis is ongoing.

- What species of Mysidae shrimp are present in coastal lagoons and how abundant are they? Mysidae are known to be an important food source for lagoons fish, but no information exists about their species composition or abundance in these environments. WCS is currently collecting Mysidae samples from the lagoons for expert analysis.

- How often do algal blooms occur at lagoons, and what effect do they have on fish and subsistence harvesters? This is a topic of local interest and may be investigated in the future.

Courtesy of Mike Lunde, Wildlife Conservation Society

How monitoring and researching lagoon ecology can help park managers

Regardless of what drives the changes observed in coastal lagoons, they may affect fish distribution and availability to subsistence harvesters. Warmer temperatures caused by climate change could reduce the quality of fish habitat by decreasing dissolved oxygen levels and causing harmful algal blooms. Changing storm frequency and freshwater runoff could alter the timing and duration of lagoon connectivity to the ocean, which dictates fish movements and overwinter survival. Longer open-water seasons and milder winters could result in invasion of non-native or boreal species, which may result in trophic cascades. Collectively, all these factors would impact the ability of local harvesters to forage for fish and wildlife that they need for food security, and may affect the quality of experience for tourists hoping to enjoy these wild and scenic landscapes.

Monitoring and additional understanding of coastal lagoon ecosystems is extremely important in order to recognize and react to any future disturbances or changes. The Wildlife Conservation Society, NPS, and the Native Village of Kotzebue Environmental Program are dedicated to the conservation of wild resources and the health of fish and wildlife populations in the Western Arctic National Parklands. We will continue to work together to monitor and study coastal lagoon ecosystems, and conduct science outreach to stakeholders and the general public.

Discover more about our lagoons monitoring with our partner Wildlife Conservation Society

Documentation of successful breeding of Caspian terns in the Arctic (2017)

Diet study of lagoon fish species of subsistence importance (2018)

Remote sensing assessment of winter lagoon habitat for fishes (2018)

Zooplankton diversity, abundance, and inter-annual dynamics in lagoons (2020)

The influence of freshwater input and marine connectivity on lagoons fish (2021)

Energy density, lipid, and protein content of lagoons fish of subsistence importance (2021)

Kevin Fraley

Fisheries Ecologist, Arctic Beringia Program

Wildlife Conservation Society

kfraley@wcs.org