Last updated: May 25, 2023

Article

Climate Change and Declines in Mojave Desert Bird Diversity

NPS Photo/Jane Gambel

Biodiversity in bird communities has declined drastically over the past century in the Mojave Desert, according to a recent landmark study by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley. The team compared historic data from bird surveys conducted as much as a century ago to recent resurveys at the same locations (including more than a dozen sites in Joshua Tree National Park). They found an average 43 percent decline in bird species diversity. Reduced precipitation, a consequence of climate change, seems to be driving the declines.

Drawing on Data from the Past

The study used historic data sets from a project launched early in the 20th century by Joseph Grinnell, the founding director of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at UC Berkeley. Using field notes from that study, a team led by biologists Kelly Iknayan and Steven Beissinger (2018) was able to find and resurvey 55 of the same Mojave desert locations, and added 6 more sites, all on federal lands that have been protected from direct impacts of human activities like farming, livestock grazing, housing development, mining, and alternative energy development.

Back Into the Field

The new round of fieldwork used standard avian transect sampling protocols, adapted to enhance comparability with the historic data. Sophisticated multispecies statistical occupancy models were used to compare the time periods and control for factors such as variations in species detectability.

Raven: NPS/Jane Gamble

Dove: NPS / Susie King

The Takeaway? Fewer Bird Species

Grinnell and his colleagues had documented 135 species of breeding birds at the 61 sites. In the resurvey, 39 species were less likely to be found at any given site. Although other studies have documented birds expanding their ranges northward with climate change, the only species to appear at more locations were the common raven (thriving because human activity creates new food sources for them) and four non-native species. Overall, most individual sites had fewer birds species; bird diversity declined significantly on 55 of the sites. The modern surveys found, on average, about 18 fewer species at each site than in the past—a 43 percent decline.

In general, birds that were already rare a century ago, such as mountain quail and Lawrence’s goldfinch, are even rarer today. One group, the raptors—including prairie falcon, American kestrel (shown above), and sharp-shinned hawk—has all but disappeared from many sites. A related study (Riddell et al., 2019) shows that the physiological effects of climate stress are especially harsh on larger birds and those with animal-based diets, like raptors and

insectivores.

The overall findings are supported by the Breeding Bird Survey, a long-term citizen science project. Field observations by volunteers document a 46 percent decline in desert bird “indicator species” since that survey launched in 1968.

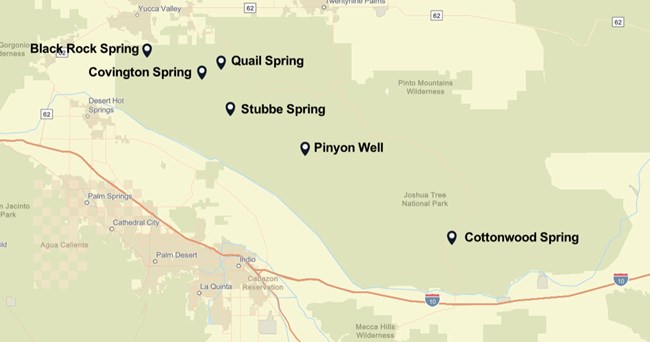

(NPS Map / Bill Carlsen)

A Complementary Study

In 2016-17, San Diego Natural History Museum biologists Lori Hargrove and Philip Unitt led a project that complements the Berkeley team's transect-focused approach. Like the Grinnell-era surveys, the San Diego effort involved multi-day field camps so biologists could carefully document vertebrate natural history. The team carried out intensive bird studies at six locations in Joshua Tree National Park; their visits were seasonally timed to correspond to visits by Grinnell-era researchers Alden Miller and Robert Stebbins in 1945–1953.

Hargrove and Unitt found that water resources had dwindled or disappeared at all six sites; only Stubbe Spring and Cottonwood Spring still have some surface water. Two of the sites had extensive damage from wildland fires, and a significant amount of pinyon/juniper and scrub oak habitat has been lost to long-term drought.

This study found that the Park has experienced dramatic reductions in mountain and chaparral birds. Changes in the composition of bird communities were notable at all sites except Cottonwood Spring. Many Grinnell-era species were less abundant or absent, with notable decreases in mountain quail, oak titmouse, blue-gray gnatcatcher, gray vireo, and Western screech owl. Common ravens, on the other hand, were more frequently observed, and there was strong evidence that the California towhee has extended its range into the Park. In the future, fire and reduced precipitation are likely to also threaten such species as California scrub jay and spotted towhee.

NPS / Alan Schmierer

Why is Diversity Declining?

The researchers have surveyed other non-desert ecosystems originally studied by Grinnell, and in those locations, bird populations have maintained their diversity. So why are bird populations collapsing in the Mojave Desert? With climate change, deserts have dried out faster than other ecoregions, so birds there now have less access to one of life’s essentials, water. The Mojave today receives 20 percent less precipitation (rain and snow) than it did in the early 20th century. Shortages of water, rather than the direct effects of higher temperatures, appear to be making this desert less habitable to many bird species.

Why Avian Diversity Matters

Birds are pollinators, scavengers, top predators, and a vector for seed distribution. So when bird communities become less diverse, the normal functioning of natural plant and animal communities may be disrupted. Undeveloped desert land may appear ideal for renewable energy projects. But solar and wind farms affect desert vegetation structure, potentially reducing habitat and food needed by birds. As the West dries and reservoirs shrink, communities are eyeing every drop of water—the same water that feeds the dwindling number of desert springs birds and other wildlife rely on.