Last updated: March 17, 2023

Article

Civil War veteran of "Fighting 69th" regiment buried at St. Paul's survived six months as prisoner in North Carolina

National Park Service

Civil War Veteran of “Fighting 69th” Buried at St. Paul’s Survived Six Months as Prisoner in North Carolina

Daniel Lawlor’s service as a combat solider in the Union army lasted little only a few weeks, but he survived six months of deteriorating conditions at a prison camp in North Carolina, enjoying a lengthy post war civilian life through 1916, when he was buried at the historic cemetery at St. Paul’s Church.

A laborer born in Ireland, Lawlor signed up on July 30, 1864 in New York City, unusual since volunteering had stalled in the fourth year of the Civil War, largely because of the horrendous casualty rate in the Virginia Overland Campaign and the perception that the Union’s military offensives were stalled. Avoidance of the stigma of the draft, the lure of the $100 enlistment bonus (about $1,400 today), or the immigrant’s desire to demonstrate patriotism may have contributed to his decision. About five years older than the average recruit, the 31-year-old joined a unit offering ethnic familiarity, the New York Volunteer 69th Infantry, part of the Irish brigade, several regiments whose ranks reflected a prevalence of Emerald Isle men. The unit had also been labeled the “Fighting 69th” by Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

With the blue uniform barely fitted on the 5’9” grey eyed immigrant he was transported south to the critical front at Petersburg, Virginia, below Richmond, the Confederate capital. Private Lawlor reinforced the depleted ranks of Company F, 69th Infantry, which was part of the 1 st Division of the Army of the Potomac’s II Corps, commanded by General Winfield Hancock. The New Yorker wouldn’t be there long.

Fighting in mid August centered upon control of the Weldon Railroad, a vital Confederate supply line reaching into North Carolina. Shortly after Lawlor’s arrival, Union Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant ordered an attack designed to cut the rail link at the Battle of Globe Tavern, or the second battle of Weldon Railroad, fought August 18–21. The assault destroyed miles of track, weakening the already strained Southern supply system. Days later, at the Battle of Reams Station, the II Corps’s thrust to further disrupt that rail link was repulsed by Confederates under Major General A.P. Hill. In one of those engagements, the brown-haired Private Lawor was captured, among hundreds of Northern troops who surrendered in that cycle of battles.

The Union prisoner was transported via rail about 200 miles to a camp in Salisbury, North Carolina, entering the twilight zone of Civil War prisoners at the most perilous point of the war to be a captive. Prisoner exchanges, or cartels, conducted in the early years of the Civil War, had been suspended on orders of General Grant. In a strategic and controversial decision, supported by President Lincoln, the Union’s commander argued that exchanges helped prolong the Confederacy, and minimized the impact of the North’s great superiority in numbers. If the Union’s strategy focused on destroying the Confederate armies, allowing the South to regain troops was counter-productive, according to the general.

The Southern refusal to recognize Union black troops as legitimate combatants, leading to ghastly treatment of the United States Colored Troops, was an additional reason for withdrawal from the cartel agreements. This strategy tragically overlapped with the steep decline in availability of supplies and materials of war for the South, partly based on the Northern blockade. The result was a grave disruption of resources for the prison camps, where Union troops, deprived of food and medical provisions, began to perish in appalling numbers.

A Confederate prison had been established in an abandoned cotton factory in 1861 in Salisbury, a railroad hub about 50 miles southwest of Greensboro. The 16-acre camp included one three-story brick building and several smaller structures. Through 1864, captured Union soldiers spent relatively short periods at the stockade before exchanges were arranged. In August, with the suspension of cartels, and Union offensives producing thousands of prisoners, a facility designed for perhaps 2,500 captives was holding nearly 10,000 Northern men. Private Lawlor’s concerned wife and three young children would probably have been aware of his circumstances; relatives of imprisoned soldiers, cognizant of the camps’ horrific conditions, pleaded with Federal officials to resume the exchanges.

Pitiful sanitation, starvation and especially disease -- dysentery, small pox, pneumonia -- transformed Salisbury into a nightmarish setting during Lawlor’s six month term at the facility. Shelter, if any, consisted of a piece of cloth over holes men dug in the ground. A conservative estimate of the dead numbered 5,000, some of whom died “from sheer despondency,” according to a captive’s diary; the deceased were dropped into nearby mass trench graves.

One of the fortunate soldiers who survived, Private Lawor gained parole in mid February 1865 when exchanges resumed. His last few months of Union service included a 30-day furlough in New York, a welcome period of reunion with his family and recuperation, given his likely emaciated condition upon release from Salisbury. Promoted to corporal, he was mustered out on June 30, beginning a civilian life in Gilded Age America that lasted longer than his pre-war years.

We might pause to consider the effect of the prison experience with the understanding that Union detainees suffered a range of post-war social and personal difficulties. Lawlor was accused by a Massachusetts soldier of siding with the South during his imprisonment, and, according to one account, as many as 2,000 men did defect to the Confederacy to escape prison life. A post war investigation found that allegation of joining the rebellion erroneous. While the inquiry was requested by Lawlor in conjunction with a pension application, the effort to exonerate his record still reflects pride in having outlasted the term at Salisbury without capitulating to the enemy. Based on available documentation, he suffered no outward emotional or psychological impact, living comfortably for another 51 years, holding steady employment and maintaining an ordinary family life.

The Lawlors sensibly relocated to the St. Paul’s vicinity in Westchester County, about 20 miles north of New York City, which was experiencing growth in population, housing stock and employment opportunities. Daughters Henrietta and Susan found work as seamstresses, and the family was secure enough that his 17-year-old son Norman studied law in 1880; Lawlor’s wife Jane was “keeping house,” according to the census. The Union veteran held a series of modest paying jobs, initially a laborer, but subsequently earned income as a jailer, further indication that there was little emotional fallout from the six months at the prison camp. Finally the veteran corralled stray animals until claimed by rightful owners as the local pound master, a historic but vanishing occupation by the early 20th century.

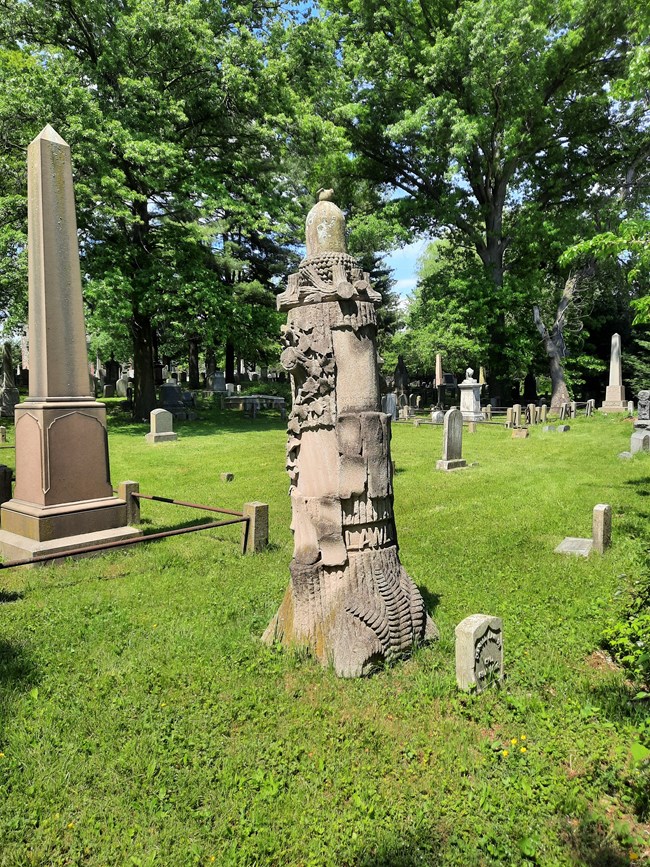

The family of seven, which included one of the daughter’s husband and an adopted girl, lived about a mile from St. Paul’s, although as Catholics they were not regular congregants in the Episcopal church. In the late 19th century many local families purchased burial rights in the church yard, one of the area’s few cemeteries. A marble tree trunk, capped with an acorn, symbolizing the renewal of life, prominently marks the Lawlor plot. The monument was supplied by the life insurance company Woodmen of the World. The former corporal from the Fighting 69th was interred on October 26, 1916, preceded in burial by his wife, a daughter and a granddaughter.