Last updated: September 23, 2021

Article

The Civil War's Impact on Schools for the Deaf and the Blind in the South

Like most other activities in the south during the Civil War, deaf education came nearly to a halt between 1861 and 1865. As a highly specialized undertaking, deaf education occurred mainly in institutions. Here, parents could send their children with hearing loss to a place where they would get education, as well as room and board. These institutions in the north incorporated the current events into their lessons and after-school activities. However, the ones in the south faced financial hardships, safety concerns of battles near the schools, and creative ways to keep the school open despite growing pressure to abandon the buildings for soldiers’ hospitals.

Photo credit: wikimedia public domain by Cculbert007

Georgia School for the Deaf

The Georgia Institution for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb in Cave Spring (now Georgia School for the Deaf) sent its students home in 1862 due to a decrease in financial support. Two orphan students stayed in the building with a foster family. The family sold some of the furniture and bedding to earn money to support the girls. Then, the Confederate and Union troops took turns using the institute for a hospital. Upon return to school in 1867, students reported seeing bloodstains on the floor and writing on the walls.

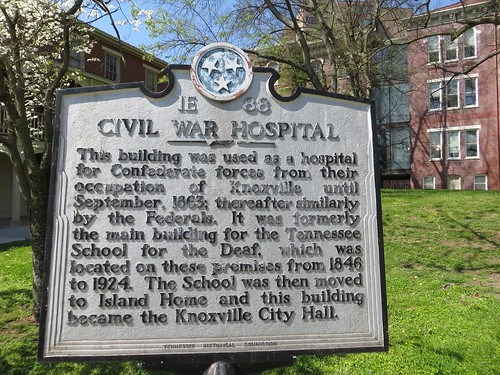

Photo credit: "Historic Places In and Around Knoxville, Tennessee"

Tennessee School for the Deaf

A similar fate happened with the Tennessee Institution for the Deaf and Dumb in Knoxville (now Tennessee School for the Deaf). The principal sent the students home early for the end of the school year in 1861 due to the announcement of Tennessee’s decision to secede from the Union. These students would not return for many years. The school was used as a military hospital. The grounds were also used as a military camp for Confederates while they were in Knoxville. A battle emerged at the school and cannon fire destroyed the roof. Union forces took over and the school’s dining room was used as a horse stable.

Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind

The Virginia Institution for the Deaf, Dumb, and the Blind (now Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind) was given to the Confederate army by the governor. The school had a section for sick and one for wounded soldiers. The north basement of the school was used as a morgue. The grounds were used as a training base for the soldiers. The school’s female teachers provided support to the soldiers by preparing bandages and sewing. Students who remained at the school over the summer wanted to help as well. When school proposed to start in the fall, these students were sent to another location away from the school. Those that went home for the summer were not allowed to return to school.

Louisiana School for the Deaf

The Louisiana Institution for the Deaf, Dumb, and Blind (now the Louisiana School for the Deaf and the Blind) also became a military hospital. The principal taught the small number of students who remained at the school due to being homeless. These students paid for the school’s operations by holding selling baked goods and vegetables from their gardens. When the Union gunboats shelled the town of Baton Rouge, the school was not spared. The assistant matron actually rowed a boat out to the gunships to request the cannons avoid the school. Her request was not granted. During the attacks, many civilians ran to the school for safety in its five-story building. Later, the building was split into two sections: one for a Union hospital and one for the school. Several soldiers wrote in their journals about watching the deaf and blind students in their studies, as well as watching battles from their hospital window.

Photo credit: Library of Congress #91721174

Mississippi School for the Deaf

The Mississippi Institution for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb (now the Mississippi School for the Deaf with the School for the Blind next door) also became a military hospital. However, it suffered a worse demise. The students were either sent home or to other locations outside of the state, if they were homeless, until it was safe to return to Jackson and their school. In the meantime, the principal joined the Confederate infantry and died in battle. During the Siege of Jackson in 1863, the school remained standing and operational as a hospital yet suffered a lot of destruction. When Sherman and his troops left the town, they burned whatever they could. The school, including all school records, was gone.

South Carolina School for the Deaf and the Blind

Not all the southern institutions became military hospitals though. South Carolina Institution for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb and the Blind (now South Carolina School for the Deaf and the Blind) never saw military action on their grounds in Cedar Springs. However, like other schools, their funding from the state was cut off. So, they continued educating their approximately thirty students with meager resources. One private of the 5th South Carolina Infantry was spared from fighting in the war when his father, the principal of the school, died from measles and his mother received permission for him to serve as steward of the school.

North Carolina School for the Deaf and the Blind

The North Carolina Institution for the Deaf and Dumb and the Blind (now North Carolina School for the Deaf and the Blind) became directly involved with the Confederate army. The principal, Willie J. Palmer, continued educating the students while also boosting their vocational program. The boys in the program made cartridges while the girls sewed shirts and other items for the soldiers. The vocational program also had a printing press that helped to publish such journals as the American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb. Since the publication was suspended at the beginning of the war, the male students began printing training manuals for state military forces, as well as paper money for the Confederacy. Despite the Confederate army wanting the institution for a military hospital, the North Carolina Institution avoided this fate by its immense production of resources for the army. In fact, the school’s vocational program was doing so well that it actually increased enrollment to just under one hundred students and made extra money for operations during the Civil War years.

Tags

- brices cross roads national battlefield site

- chickamauga & chattanooga national military park

- fort sumter and fort moultrie national historical park

- gettysburg national military park

- kennesaw mountain national battlefield park

- shiloh national military park

- civil war

- kennesaw mountain national battlefield park

- kemo

- deaf history

- deaf awareness

- disability awareness