Part of a series of articles titled Intermountain Park Science 2021.

Article

Citizen-based Acoustic Bat Monitoring Along the Colorado and San Juan Rivers

- Grace M. Carpenter, Biologist, Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division, National Park Service (currently Wildlife Biologist, Upper Williamette Resource Area, Bureau of Land Management)

- Lonnie Pilkington, Natural Resources Program Manager, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, National Park Service (currently Vegetation Program Manager, Grand Canyon National Park, National Park Service)

- Emma C. Wharton, Executive Director, Grand Canyon Youth

- Shandiin J. Tallman, Biological Science Technician, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, National Park Service (currently Facility Service Assistant, Flagstaff Area National Monuments, National Park Service)

- Michael L. Berg, Biological Science Technician (former), Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, National Park Service

Abstract

The rise of urgent environmental issues in National Parks has led resource managers to pursue citizen-based research projects to aid in the collection of scientific data. From 2016–2018, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area partnered with Grand Canyon Youth, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization based in Flagstaff, AZ and other organizations to collect data on the distribution of bat species within the park while simultaneously engaging youth and young adults in resource stewardship, citizen science, and service-learning. We collaborated with six schools and seven youth programs in the region, engaging 276 youth and 80 young adult leaders including teachers and river guides in collection of bat monitoring data. We led 18 river trips to a total of 17 locations along the San Juan and Colorado Rivers. Participants gathered 46,909 acoustic data files which we identified to 14 bat species. This data set will inform the management of bat species as the threat of white-nose syndrome (a devastating fungal disease that affects many bat species and has killed millions of bats in USA and Canada in recent years) grows in the western United States. Cooperative agreements made with education-oriented outdoor adventure organizations may be an expedient method for growing future citizen science programs in the National Park Service.

Introduction

Bats provide important ecological services such as insect control, plant pollination, and seed dispersal (Beeker et al. 2013), but unfortunately are often undervalued, feared, and insufficiently researched (Barlow et al. 2015). In addition, bat populations are subject to stressors including habitat loss, disease (e.g., white-nose syndrome), wind energy development, climate change, and malicious destruction by humans. Bats have recently been propelled into the public eye and provide a ripe opportunity for public land management agencies to partner with non-governmental entities to engage the public in citizen science to further monitoring and conservation efforts.

For years, non-professionals have been noting natural resource observations (Miller-Rushing et al. 2012) in their beloved National Parks. These observations have enabled park resource managers to realize the importance of these records, better understand the natural ecosystems they manage, and embrace the emerging field of citizen science (Ellwood et al. 2016). National Park Service (NPS) units provide amazing outdoor classrooms for citizen science discovery of under-studied species such as bats. Until recently, citizen science-based bat monitoring efforts have been uncommon, but user-friendly bio-acoustic technology (Barlow et al. 2015) and increased access to adequate training has helped reverse this trend.

Data on the status of bat populations on NPS lands are lacking (Rodhouse et al. 2016) which has prompted federal land management agencies to partner with non-governmental entities and engage citizen scientists to accomplish conservation objectives (Mitchell et al. 2002). The Federal Grant and Cooperative Agreement Act of 1977 provides an avenue for government agencies to enter into cooperative agreements to transfer funding to partnering entities to accomplish common goals where public purpose and substantial involvement exists. Partnerships that engage citizen scientists cultivate informal education opportunities, contribute critical data to long-term datasets, and further wildlife conservation efforts (Forrester et al. 2017).

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area is an NPS unit for which bat monitoring data are greatly lacking, therefore we implemented a citizen science study to inform future management decisions. The goal of this study was to provide an opportunity for the National Park Service, partners, and citizen scientists to (i) collectively conduct bio-acoustic monitoring to better understand the local distribution and habitat usage of bat species in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area; (ii) collect high quality quantitative data to further continent-wide bat conservation efforts; and (iii) cultivate lifelong National Park Service ambassadors. To accomplish these goals, we partnered with Grand Canyon Youth and river rafting outfitters to engage youth in the bat monitoring process along the San Juan and Colorado Rivers. In this paper we summarize how citizen scientists, partners, NPS, and bats have mutually benefited; and provide recommendations for improving and expanding this program to include other NPS units and entities.

Study Area

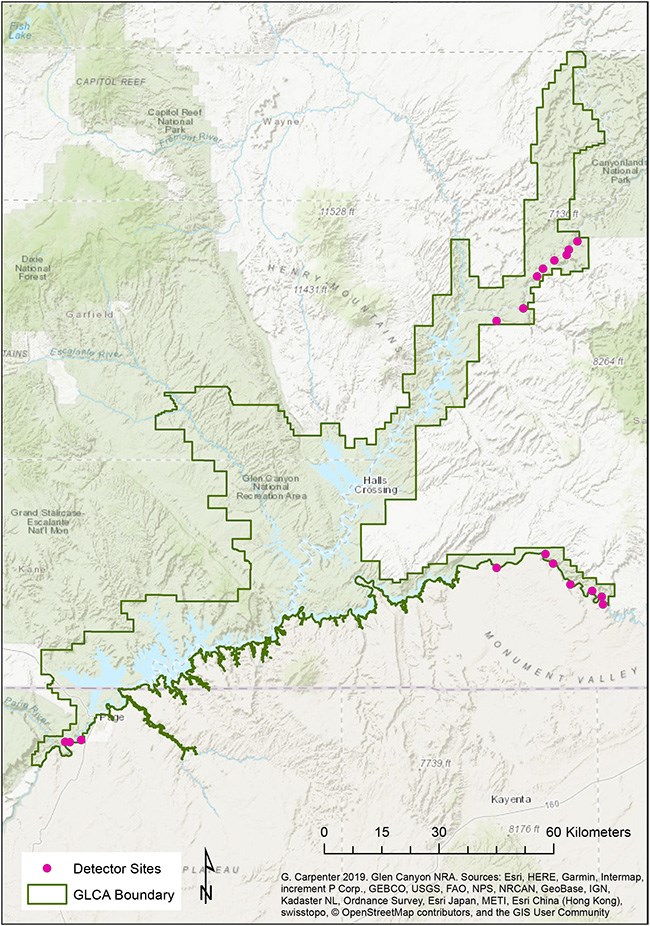

Located on the Colorado Plateau, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area encompasses 505,868 ha and ranges in elevation from 930–2319 m (Figure 1). The topography of the recreation area contains ample roosting habitat for bats in the form of cracks, crevices, and talus slopes (Adams 2003). We implemented the project in three regions of the park to coincide with trip routes established by our partners; Cataract Canyon between Colorado River mile 202 and the Hite, Utah take out (32 miles); the San Juan River between river mile 45 and the Clay Hills, Utah take out location (38 total river miles); and the lower Colorado River between Horseshoe Bend, Arizona and the Lee’s Ferry, Arizona take out (9 miles).

Methods

Our study took place between May 4–October 24 in 2016–2018. While not all sites were sampled in all years, a minimum of one site per region was sampled each year. We collaborated with Grand Canyon Youth, a partner with which we had an existing cooperative agreement to develop our citizen science project. We used a combination of cooperative agreements, grants, and verbal agreements to facilitate the partnership across the three study years. Specializing in leading educational youth trips on the San Juan and Colorado Rivers, Grand Canyon Youth reached out to schools and other student organizations to identify groups interested in implementing our curriculum during their river trips. The resulting groups of youth participants were primarily comprised of students from 6th–12th grade. As many of the accompanying teachers and river guides attending our presentations and participating in our research were 35 years of age or younger, we included them in our assessment of youth participants.

NPS Photo.

A staff member of the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area Division of Science and Resource Management accompanied river trips to educate all trip participants on the purpose of the research and to instruct youth on the protocols needed to implement the project. The curriculum also included information on bat physiology, ecology, threats, and research and methods. We used interpretive tools to help participants experience bats in the vicinity such as the EchoMeter Touch (Wildlife Acoustics, Maynard, MA, USA), a device which identifies and displays bat echolocation calls in real-time (Figure 2), and a device (Baton; Batbox Limited, West Sussex, England) which translates high-frequency bat calls (20-80 kHz) into frequencies detectable by human ears (0.2–20 kHz) (Figure 3).

NPS photo.

We also used laminated slides to help participants visualize information (such as bat physiology and maps of white-nose syndrome spread). To cultivate NPS ambassadors, we distributed information on bat conservation following river trips, invited youth to participate in other research efforts at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, and encouraged them to pursue similar opportunities in their hometowns.

To conduct bioacoustics monitoring and characterize the distribution of bat species within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, youth deployed acoustic bat detectors (SM4BAT-FS; Wildlife Acoustics, Maynard, MA, USA) at sites along the San Juan and Colorado Rivers following protocols outlined by the NPS Guidance for Conducting Acoustic Survey for Bats (NPS 2016) (Figure 4). They placed detectors in locations which would allow for high quality recordings (i.e. in locations away from canyon walls or other smooth surfaces which could produce reverberations or harmonics, and in locations facing flight corridors).

NPS photo.

At each monitoring site, youth recorded dominant vegetation and weather conditions at time of deployment and at time of recovery. Detectors began recording at 15 minutes before sunset and ended 15 minutes after sunrise. Direct-recording full-spectrum microphones recorded echolocation calls in Waveform Audio File Format (WAV) which is a digital-audio format for uncompressed audio files that was developed by Microsoft and International Business Machines Corporation (IBM). As groups spent a single night at each consecutive river campsite, participants surveyed each site for one night per trip.

We used Sonobat (Version 4.0.6; Arcata, CA, USA) to classify bat calls and vetted (i.e., manual inspection of spectrograms) calls from species which had never been physically captured in the park. We shared data with the NPS Bats Acoustic Survey Database (Version 1.7), and the North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat; Loeb et al. 2015), a continent-wide effort to monitor bat species and aid local and range-wide management decisions.

Results

We garnered participation from seven schools that showed interest in the program: Kanab High School, Northland Preparatory Academy, Orangewood Middle School, Page High School, Page Middle School, Sinagua Middle School, and Spring Street International School. Additionally, students participated on this project through six different youth programs: Grand Canyon Youth Canyon Discovery, Grand Canyon Youth Middle School Adventure, Haven, No Barriers Youth – Children of the Fallen, No Barriers Youth – Learning Afar, and Southwest Conservation Corps Ancestral Lands Program. Across all schools and programs involved, 276 students participated in these research efforts (Figure 5). We engaged an additional 80 young adults under the age of 35 including 20 teachers and 60 river guides, excluding one trip for which we could not obtain demographic data of teachers and guides.

We led 18 trips which collectively included surveys at 17 sites; seven along the San Juan River, seven in Cataract Canyon, and three along the lower Colorado River. We visited each site one to eight times throughout the three-year study period. We collected a total of 46,909 acoustic call files, 28,209 of which were of high enough quality to be identified to species (Table 1–3). We identified 14 bat species including the first record of the greater mastiff bat (Eumops perotis) within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area boundaries, detected at 10 sites including at least one site per region. We also detected the Brazilian free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis), pallid bat (Antrozous pallidus), big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus), spotted bat (Euderma maculatum), Allen’s big-eared bat (Idionycteris phyllotis), silver-haired bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans), hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus), California myotis (Myotis californicus), western small-footed myotis (M. ciliolabrum), fringed myotis (M. thysanodes), long-legged myotis (M. volans), Yuma myotis (M. yumanensis), and canyon bat (Parastrellus hesperus). Several calls were classified as western red bat (Lasiurus blossevillii) and little brown bat (M. lucifugus) however, we could not confirm either species with manual vetting. Similarly, while several calls were classified as “Nyctinomops species,” SonoBat (Version 4.0.6) cannot reliably distinguish the expected big free-tailed bat (N. macrotis) from other species within the genus, so it was not confirmed.

|

|

Lower 10 Cent |

Waterhole Canyon |

Gypsum Canyon |

RM 194 |

Slab |

Dark Canyon |

Mille Crag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of Nights Surveyed |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

Species |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Greater mastiff bat |

1.0 |

0.0 |

11.0 |

5.0 |

12.3 |

4.5 |

53.0 |

|

Brazilian free-tailed bat |

11.0 |

0.0 |

3.0 |

1.0 |

30.7 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Pallid bat |

2.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

4.0 |

0.0 |

9.0 |

|

Big brown bat |

13.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

|

Allen’s big-eared bat |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

3.0 |

1.7 |

0.5 |

1.0 |

|

Silver-haired bat |

11.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

2.0 |

9.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Hoary bat |

11.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

2.0 |

|

California myotis |

58.0 |

20.0 |

97.0 |

38.0 |

79.7 |

16.0 |

34.0 |

|

Fringed myotis |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.7 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Yuma myotis |

7.0 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

6.0 |

3.7 |

2.0 |

1.0 |

|

Canyon bat |

159.0 |

239.0 |

240.0 |

737.0 |

180.0 |

425.0 |

626.0 |

|

Total |

273.0 |

260.0 |

351.0 |

793.0 |

323.4 |

448.5 |

726.0 |

|

|

Twin Canyon |

Upper Twin Canyon |

Ross Rapid |

Johns Canyon |

Government |

Slickhorn |

Oljeto |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of Nights Surveyed |

3 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

7 |

8 |

|

Species |

|

||||||

|

Greater mastiff bat |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

7.3 |

0.0 |

7.4 |

22.8 |

|

Brazilian free-tailed bat |

5.7 |

26.0 |

0.0 |

23.3 |

4.0 |

51.0 |

141.6 |

|

Pallid bat |

1.7 |

452.0 |

0.0 |

8.7 |

0.0 |

10.0 |

20.0 |

|

Big brown bat |

0.0 |

83.0 |

0.0 |

3.7 |

0.0 |

25.1 |

1.1 |

|

Spotted bat |

0.0 |

51.0 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

|

Allen’s big-eared bat |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

|

Silver-haired bat |

1.3 |

28.0 |

0.0 |

5.3 |

0.0 |

5.1 |

2.6 |

|

Hoary bat |

0.0 |

2.0 |

1.0 |

4.3 |

2.0 |

3.6 |

8.9 |

|

California myotis |

88.7 |

88.0 |

64.0 |

81.0 |

496.0 |

402.7 |

468.0 |

|

Western small-footed myotis |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

|

Fringed myotis |

0.7 |

27.0 |

1.0 |

6.0 |

15.0 |

4.1 |

0.0 |

|

Long-legged myotis |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.4 |

|

Yuma myotis |

5.3 |

79.0 |

4.0 |

7.3 |

4.0 |

54.0 |

28.0 |

|

Canyon bat |

210.7 |

1912.0 |

25.0 |

303.3 |

197.0 |

510.7 |

330.4 |

|

Total |

314.1 |

2748.0 |

96.0 |

450.5 |

718.0 |

1074.1 |

1024.2 |

|

|

Horseshoe Bend |

6-mile Camp |

Lunch Beach |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of Nights Surveyed |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Species |

|

||

|

Greater mastiff bat |

0.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Brazilian free-tailed bat |

233.5 |

84.0 |

1.0 |

|

Pallid bat |

0.5 |

0.0 |

2.0 |

|

Big brown bat |

0.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Silver-haired bat |

50.5 |

30.0 |

0.0 |

|

California myotis |

140.5 |

52.0 |

1.0 |

|

Fringed myotis |

9.0 |

2.0 |

0.0 |

|

Yuma myotis |

88.5 |

3.0 |

1.0 |

|

Canyon bat |

414.5 |

107.0 |

16.0 |

|

Total |

938.0 |

278.0 |

21.0 |

The San Juan River region had the greatest species richness (number of species) with recordings of all 14 species and was the only region with recordings of western small-footed myotis and long-legged myotis (Table 2; Figure 6). Two bat species, California myotis and canyon bats were the most ubiquitous, recorded at all 17 sites in all years except for Lunch Beach in 2018. Oljeto and Slickhorn Canyon of the San Juan River region were the two most visited sites with eight and seven nights of sampling respectively over the duration of the study, thus we have the greatest total number of recordings from these sites. The Upper Twin Canyon site had the greatest mean number of calls per night.

Discussion

With the data collected from this project, we established baseline distribution of bat species in three regions of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Based on bat species range maps (Adams 2003, Rodhouse et al. 2016) and studies on adjacent public lands (Berna 1990, Bogan et al. 2006, Flinders et al. 2002, Foster et al. 1996, Mollhagen and Bogan 1997, Stroud-Settles and Tobin 2015) we expected to confirm presence of the following 18 species: big free-tailed bat (Nyctinomops macrotis), Brazilian free-tailed bat, pallid bat, Townsend’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii), big brown bat, spotted bat, Allen’s big-eared bat, silver-haired bat, western red bat, hoary bat, California myotis, western small-footed myotis, western long-eared myotis (Myotis evotis), little brown bat, fringed myotis, long-legged myotis, Yuma myotis, and canyon bat. Of the 18 species likely to occur within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, citizen scientists documented 13 of the expected species and one additional species through acoustic detection. The unexpected species was the first park record of a greater mastiff bat. Acoustic recordings of greater mastiff bats were significant since range maps for this species (Adams 2003, Rodhouse et al. 2016) do not overlap Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. This study did not confirm presence of the following expected species: big free-tailed bat, Townsend’s big-eared bat, western red bat, western long-eared myotis, and little brown bat. These data will form the basis of a long-term bat monitoring program, and potentially reveal future dynamics in the bat community as large-scale phenomena, such as climate warming or introduction of White-Nose Syndrome (WNS), impact the Glen Canyon region.

The San Juan River region had the greatest species richness of all the regions in our study. Similarly, individual sites within the San Juan River region had the greatest species richness among all sites surveyed. These results are at least partially due to different numbers of sampling visits. The San Juan River sites were surveyed a total of 24 times while the Cataract Canyon and lower Colorado River regions were only surveyed 10 and four times, respectively. Timing of surveys can also affect how many bats are detected. Surveys of the San Juan River region took place from May 15–July 1, whereas surveys of Cataract Canyon and the Lower Colorado River primarily took place in early May or in September or October. Thus, as bats’ most active time of the year takes place during the summer breeding season (Adams 2003) surveys of the San Juan River may have produced a greater number of calls due to the increase in activity. Species richness and number of individuals within a species were also potentially affected by the uneven sampling effort across locations and seasons. Increased surveys at the Cataract Canyon and lower Colorado River sites with effort spread more evenly across the summer months may help determine whether differences in species richness are due to sampling methods or whether other factors (e.g. habitat availability, differences in seasonal usage, etc.) are affecting distribution.

We engaged 356 total youth in citizen science and educated them on bat research methods and the urgency of threats facing North American bat species. We also garnered youth participation in collection of data for an aquatic food base study (USGS 2019), the national Dragonfly Mercury Project (Eagles-Smith et al. 2018), and inventory and control of invasive non-native plants on certain trips. Many youth reported that the experience as a whole changed their perspective on the outdoors. One student, Robyn Nelson (2017 and 2018 participant) said “The Grand Canyon Youth River Trip has impacted the way I am today by exploring the beautiful landscape of the San Juan River, it made me see things in a different perspective…to enjoy the outdoors. The trip helped me get out of my comfort zone and to conquer my fears. It was also a great educational experience!” Several other participants have gone on to volunteer with Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, and one later obtained a job with Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. Implementation of post-trip surveys may allow for better measurement of overall curriculum effectiveness, and long-term study may help determine whether participation influenced future involvement with NPS or other science-based endeavors.

The use of cooperative agreements, grants, and verbal agreements enabled us to engage youth in this citizen science project at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Partnering with organizations that have the infrastructure to help non-scientists access remote areas in this way made it possible for us to generate valuable monitoring data in a cost-effective manner. Future partnerships with adjoining NPS units and other public land units may allow for similar education and scientific goals to be met on a larger scale. Partnering with education-oriented outdoor leadership industries through cooperative agreements or other arrangements may be an expedient method for growing future citizen science programs in the NPS.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NPS Centennial Challenge, NPS Challenge Cost Chare, Grand Canyon Youth, Glen Canyon Conservancy, and the Outdoor Foundation for facilitating our research. We also thank our interns from the NPS Mosaics in Science, Student Conservation Association, and NPS Academy programs, and the many Glen Canyon National Recreation Area Biological Science Technicians who provided bat conservation education and organized data collection during river trips including Vanessa Armentrout, Ben Brogie, Michael Fuerte, Brad Jorgensen, Katherine Ko, Alexis Levorse, Steven McIntyre, Roy Morris, Kayla Overright, Jessica Rosado, Razia Shafique, and Ashley Xu.

References

Adams, R. A. 2003.

Bats of the Rocky Mountain West: Natural History, Ecology, and Conservation. University Press of Colorado, 289 pp.

Barlow, K. E., P. A. Briggs, K. A. Haysom, A. M. Hutson, N. L. Lechiara, P. A. Racey, A. L. Walsh, and S. D. Langton. 2015.

Citizen science reveals trends in bat populations: The National Bat Monitoring Programme in Great Britain. Biological Conservation 182:14–26.

Beeker, T. A., K. F. Millenbah, M. L. Gore, and B. L. Lundrigan. 2013.

Guidelines for creating a bat-specific citizen science acoustic monitoring program. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 18:58–67.

Berna, H. T. 1990.

Seven bat species from the Kaibab Plateau, Arizona, with a new record of Euderma maculatum. The Southwestern Naturalist 35:354-356.

Bogan, M. A., T. R. Mollhagen, and K. Geluso. 2006.

Inventory for bats at Canyonlands National Park, Utah. National Park Service Unpublished Report, Moab, Utah.

Eagles-Smith, C. A., S. J. Nelson, C. M. Flanagan-Pritz, J. J. Willacker Jr., and A. Klemmer. 2018.

Total mercury concentrations in dragonfly larvae from U.S. National Parks (2014-2017): U.S. Geological Survey data release. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5066/P9TK6NPT (accessed August 21, 2020)

Ellwood, E.R., T.M. Crimmins, and A.J. Miller-Rushing. 2016.

Citizen science and conservation: recommendations for a rapidly moving field. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.10.014 (accessed August 21, 2020)

Flinders, J. T., D. S. Rodgers, J. L. Weber-Alston, and H. A. Barber. 2002. Mammals of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument: A literature and museum survey. Monographs of the Western North American Naturalist 1:1–64.

Forrester, T. D., M. Baker, R. Costello, R. Kays, A. W. Parsons, and W. J. McShea. 2017.

Creating advocates for mammal conservation through citizen science. Biological Conservation 208:98–105.

Foster, D. A., L. Grignon, E. Hammer, and B. Warren. 1996.

Inventory of bats in high plateau forests of central and southern Utah. National Park Service Unpublished Report, Bryce Canyon National Park, Bryce Canyon, Utah.

Loeb, S. C., T. J. Rodhouse, L. E. Ellison, C. L. Lausen, J. D. Reichard, K. M. Irvine, T. E. Ingersoll, J. T. H. Coleman, W. E. Thogmartin, J. R. Sauer, C. M. Francis, M. L. Bayless, T. R. Stanley, and D. H. Johnson. 2015.

A plan for the North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat). General Technical Report SRS-208, U.S. Forest Service, Asheville, North Carolina.

Mitchell, N., B. Slaiby, and M. Benedict. 2002.

Local community leadership: building conservation partnerships for conservation in North America. Parks 12:55–66.

Miller-Rushing, A., R. Primack, and R. Bonney. 2012.

The history of public participation in ecological research. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 10(6):285–290.

Mollhagen, T. R., and M. A. Bogan. 1997.

Bats of the Henry Mountains region of southeastern Utah. Occasional Papers: Museum of Texas Tech University 170:16.

National Park Service (NPS). 2016.

Guidance for conducting acoustic monitoring of bats: detector deployment, file processing, and database v. 1.7. Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/NRR—2016/1282. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. Available at: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/DownloadFile/554416 (accessed August 24, 2020)

Rodhouse, T. J., T. E. Philippi, W. B. Monahan, and K. T. Castle. 2016.

A macroecological perspective on strategic bat conservation in the US National Park Service. Ecosphere 7(11): e01576. 10.1002/ecs2.1576

Stroud-Settles, J., and B. Tobin. 2015.

Bat project at Grand Canyon National Park. National Park Service Unpublished Report, Grand Canyon National Park, Grand Canyon, Arizona.

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). 2019.

Citizen science light trapping in Grand Canyon. Available at: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/sbsc/science/citizen-science-light-trapping-grand-canyon?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects (accessed August 24, 2020)

Last updated: April 30, 2024