Last updated: July 6, 2025

Article

Charles Young and the Ninth Cavalry in Sequoia National Park

National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center, Wilberforce, Ohio

Being stationed in San Francisco was a big change for the Ninth Cavalry. Previously, The Ninth Cavalry had been on the frontier, far from large metropolitan areas. Even though the men were in a city, their duty as Buffalo Soldiers continued with drill and other mundane aspects of garrison life.

Before President Woodrow Wilson signed the act creating the National Park Service within the Department of the Interior in August 1916, the Army oversaw protecting and maintaining the parks. On May 15, 1903, Captain Young and I and M Troops of the Ninth Cavalry were ordered to Sequoia and General Grant national parks. The parks were 285 miles away from the Presidio in central California’s Sierra Mountains. Young and the troopers traveled in a caravan including supply wagons, 20 draft mules, two civilian packers, and six civilian teamsters. On the journey, the men purchased forage for the animals and fresh food for themselves whenever possible.

The men arrived in Visalia, California, the closest town to Sequoia National Park, on June 2. The townspeople, who had never seen African American soldiers, celebrated their arrival. Young and his men talked to some of the African American school children who came out to see them. He encouraged the school children to aim high in their education, telling them that anything was possible.

Two days later Young and his command arrived at the parks’ entrance. He set up his headquarters and supply depot on the North Fork of the Kaweah River near the current community of Three Rivers. Young immediately got to work and dispatched groups of troopers into the parks to guard against poaching and livestock grazing. Young then went to examine what needed to be done to complete the road into Sequoia National Park, their primary objective for the summer.

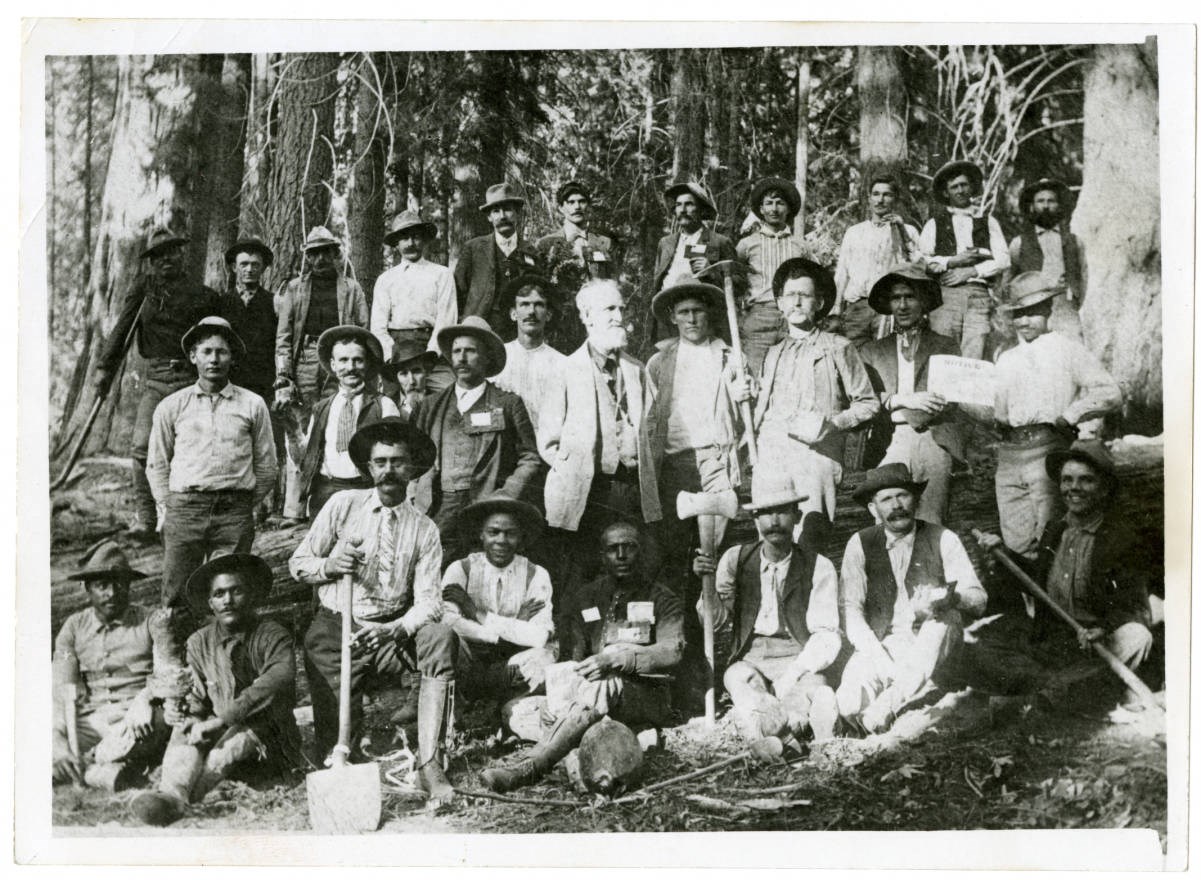

On June 11, Young, along with his civilian work crew, set to work on the access road to the Giant Forest. His goal by the end of the summer was five miles of new road. Young managed a 60-man work crew throughout the summer. One of the men he worked closely with was Walter Fry. In 1916, Fry became the first civilian superintendent of Sequoia National Park.

As the summer progressed, Young was comfortable with the work the civilian roadcrew was making, so he turned his attention to the trails and roads his troops were building in the park’s interior. He made several trips of more than 75 miles from his camp to the Mount Whitney area to check on his troopers. Those men not only protected the park from illegal grazing but also built trails to the top of Mount Whitney—the highest mountain in the contiguous United

States—from Lone Pine, California.

On August 29, 1903, Captain Young sent his report to the Department of the Interior in Washington, D.C. In the report, he wrote “I submit that more work has been done, and better work through rougher country than has been done in any two years previous to this.” Young and his men celebrated the opening of the wagon road by hitching some of their mules to wagons and riding into the Giant Forest for the first time.

When Sequoia National Park was initially preserved in 1890, there were many inholdings, or privately held tracts of land, within the park boundaries. They totaled 3,877 acres and contained roughly 9,000 sequoia trees. During Young’s travels through the park, he stopped and visited with the landowners. By the end of the summer, all the landowners had agreed to sell their inholdings to the federal government for a modest price because of their relationship with Young. Unfortunately, it took the federal government more than a decade to purchase the land, by which time the prices had tripled.

As the summer ended, the townspeople, the civilian work crew, and the troopers all agreed that a giant sequoia tree should be named after Young. He declined, stressing his role as a public servant. Young told his friend Philip Winser that he would accept the honor if they felt the same way in 20 years. Young instead wanted to name a tree after Booker T. Washington. Washington, the first principal of the Tuskegee normal school for colored teachers, which grew to become the Tuskegee Institute, was a civil rights leader of the day.

In Young’s report to the Department of the Interior, he stated: “I permitted the naming of three trees in Sequoia Park this season: One “G.A.R.” tree, in honor of the Grand Army of the Republic; another from its particular growth of three large trees from one big trunk, was named “I.O.O.F” for the Odd Fellows of the country; and the third, after repeated requests from visitors and the wishes of the workmen who finished the Giant Forest Road, was named after the great and good American, Booker T. Washington.”

Young and I and M Troops left Sequoia National Park in late October 1903 and returned to the Presidio. In the summer of 2004, 101 years after Charles Young and the Buffalo Soldiers helped preserve Sequoia National Park, a giant sequoia near the Booker T. Washington Tree was named in honor of Charles Young. The Brigadier General Charles Young Tree is near the Moro Rock area of the Giant Forest and the road built by Young and his men.

In November 2019, the section of California State Highway 198 from Salt Creek Road to the Sequoia National Park entrance in Tulare County was renamed “Colonel Charles Young Memorial Highway.”

Want to learn more about Charles Young and the Ninth Cavalry at Sequoia National Park? Read Black Officer in a Buffalo Soldier Regiment: The Military Career of Charles Young, by historian and author Brian G. Shellum.

Tags

- charles young buffalo soldiers national monument

- sequoia & kings canyon national parks

- charles young

- buffalo soldier

- buffalo soldiers

- 9th cavalry

- african american army

- african american military history

- african american history

- preservation

- giant sequoias

- americas best idea

- americans national parks

- giant forest

- 1900s