Last updated: February 22, 2023

Article

Charles Young's Medical Retirement and Protest Ride

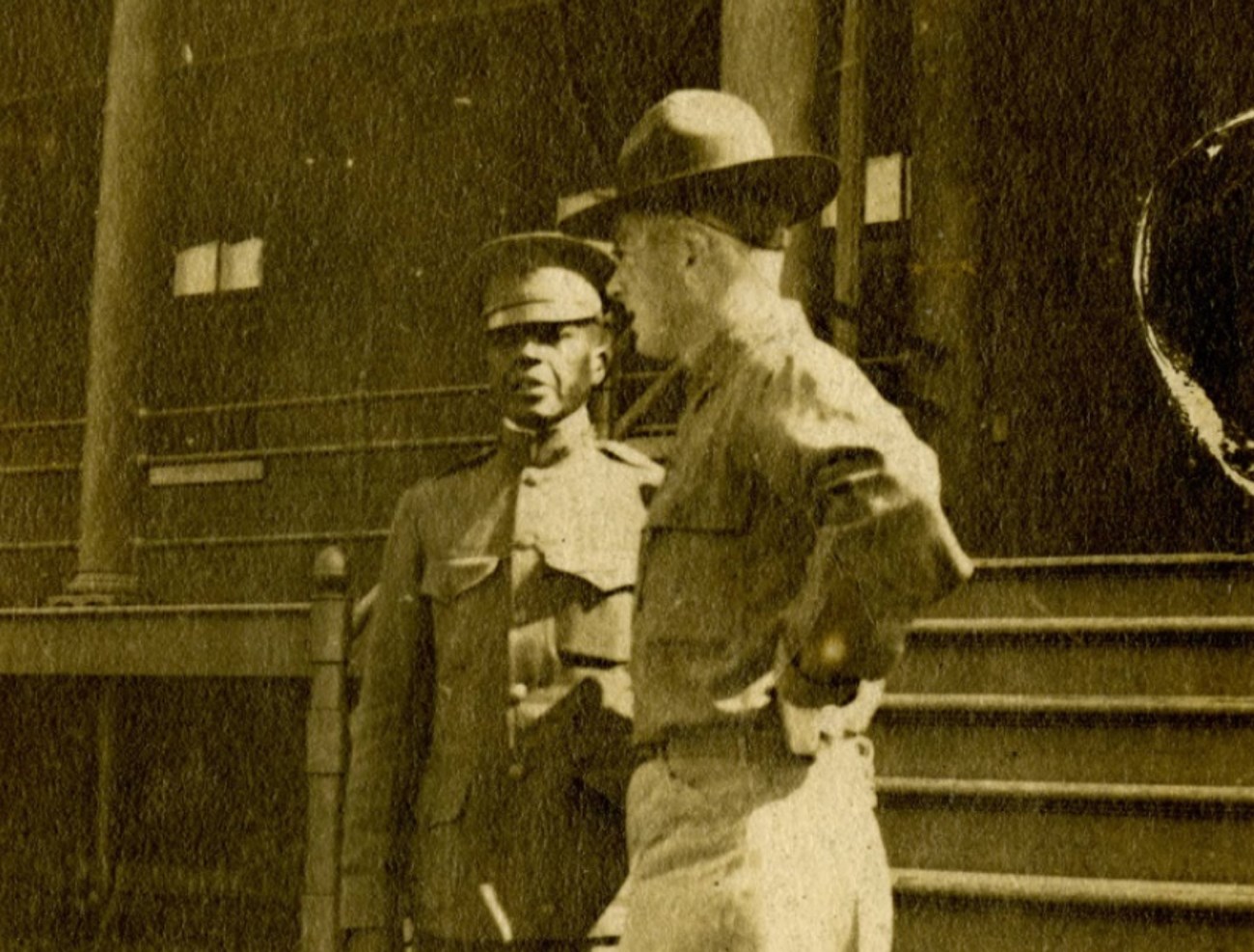

Courtesy of the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center, Wilberforce, Ohio.

Before Young planned too far in advance, he had his promotion board to colonel. Getting ready for this Young studied upon his return to Fort Huachuca. In a letter to his wife, Ada Young, Lt. Col. Young wrote “Everything is moving on O.K., although I’m obliged to study night and day to catch up.” On May 9, 1917, Young stood for his promotion board to colonel at the Southern Department Headquarters in San Antonio, Texas. The promotion board found Young professionally qualified for promotion however during the medical exam found that Young suffered from high blood pressure and albumin in his urine. Albumin in your urine is a sign of kidney disease that can be caused by multiple health issues including prolonged high blood pressure. The Army ordered Young to undergo a comprehensive medical examination before appearing in front of the promotion board again.

On June 4, 1917, Charles Young arrived at the Letterman Army Hospital in San Francisco, California to undergo the required medical examination. Young stayed at the hospital for seven days. In that time they tested his kidney, eyes, hearing and his heart. While at the hospital he wrote to his wife complaining of all the test as nothing seemed to come up as a problem. Young’s medical report that was dated June 11, 1917, was very thorough, stated otherwise. It confirmed his high blood pressure and albumin in his urine along with an enlarged heart, his left heart ventricle had marked hypertrophy and a moderate amount of arteriosclerosis. The report ended with a prognosis; “Unfavorable as to complete recovery and ability to do active field service requiring physical stress and involving endurance without danger to life.” Young was declared physically unfit for promotion by the medical board even though he had no aches, pains or any history of sickness.

An examining board convened on July 7, 1917 in San Francisco to consider Young’s fate in the army. The examining board still found him medically unfit for duty however they recommended “in view of the present war conditions the physical condition of this officer be waived and that he be promoted to the next higher grade.” The board forwarded their recommendation onto Adjutant General of Army for a final decision.

While Young was in San Francisco, correspondence between President Woodrow Wilson and Secretary of War Newton Baker would ultimately determine Young’s fate. Wilson received word from southern congressmen that some of the white officers under Young’s command were unwilling to take orders from a Black man. Wilson wrote to Baker to arrange reassignment for the white officers so they do not get court martialed for insubordination. Baker replied back to Wilson saying he also heard about white officers complaining about serving under Young. Baker was going to remedy the situation by assigning Young to train incoming Black officers at Fort Des Moines in Iowa. On July 7, Baker updated Wilson about Young’s situation. By this time Baker received Young’s medical report and told the president not to worry anymore about Young because he was medically unfit for promotion. Upon Young’s medical retirement he was promoted to colonel and placed on the unlimited retired list. Being placed on this list made it possible for Young to continue to serve in some capacity during the war.

Colonel Young returned to Youngsholm, his family home in Wilberforce, Ohio, before traveling to Columbus, Ohio to work with the Ohio National Guard. Young was tasked with organizing the new Ninth Ohio National Guard Regiment for federal service. This was not the first time Young worked with the Ohio National Guard. During the Spanish-American war in 1898 he was given command of the Ninth Ohio Battalion which was an all-Black infantry battalion. However, the Ninth Ohio National Guard Regiment was never meant to mobilized and only authorized for political purposes during World War One. Upon learning that the regiment was not meant to be mobilized Young returned to Wilberforce University and voluntarily resumed his duties as the professor of military science and tactics.

In the Summer of 1918, Young tried one more time to prove to the military that he was fit for duty. On June 6, 1918, Young saddled his black mare named Blacksmith and headed east to Washington DC on what became known as his ‘Protest Ride.’ The Protest Ride was an extension of the fitness ride cavalry officers were required to complete. Cavalry officers were required to ride 90 miles in three days. Colonel Young rode from Wilberforce, Ohio to Washington, DC a total of 497 miles in a total of 17 days. Colonel Young arrived in Washington, DC on June 22. Young was met by Emmett J. Scott, an African American man who was a special assistant to Secretary of War Baker. Scott welcomed Young to Washington, DC and lead him to a meeting with Secretary of War Baker. Baker and Young met and spoke on many topics. At the end of the meeting Baker asked Young is he would prefer a combatant or noncombatant assignment. Young answered enthusiastically “Combatant!”

Young and the Black Newspapers got their hopes up that Young would still see active combat in Europe. Their excitement was for not as Young never saw combat during the Great War. On November 6, 1918 Young was recalled to active duty and assigned to Camp Grant, Illinois. Colonel Young oversaw developing and training all-Black battalions of laborers and stevedores. Young entered his work enthusiastically and worked diligently to improve training and quality of life of the 8,000 soldiers under his command. The men Young oversaw also never saw Europe as the armistice ending World War One went into effect November 11, 1918 just five days after Young’s arrival. Young stayed in command of Camp Grant until February 1919 when he was relieved of command by the War Department. After the closing of Camp Grant Colonel Young returned to Youngsholm in Wilberforce, Ohio hoping he would get another opportunity to serve his country.

Want to learn more about Charles Young during World War One? Read Black Officer in a Buffalo Soldier Regiment: The Military Career of Charles Young, by historian and author Brian G. Shellum.