Last updated: December 20, 2021

Article

Christmas on the Emigrant Trails: Christmas 1843 at Peachtree Valley, California

Most emigrants reached the end of their long overland journey weeks or months before December 25 rolled around. A few, though, stranded or lost along the way, spent their first Christmas in the West in winter camps many miles from the settlements. Here’s how they observed the holiday.

Image/Public Domain

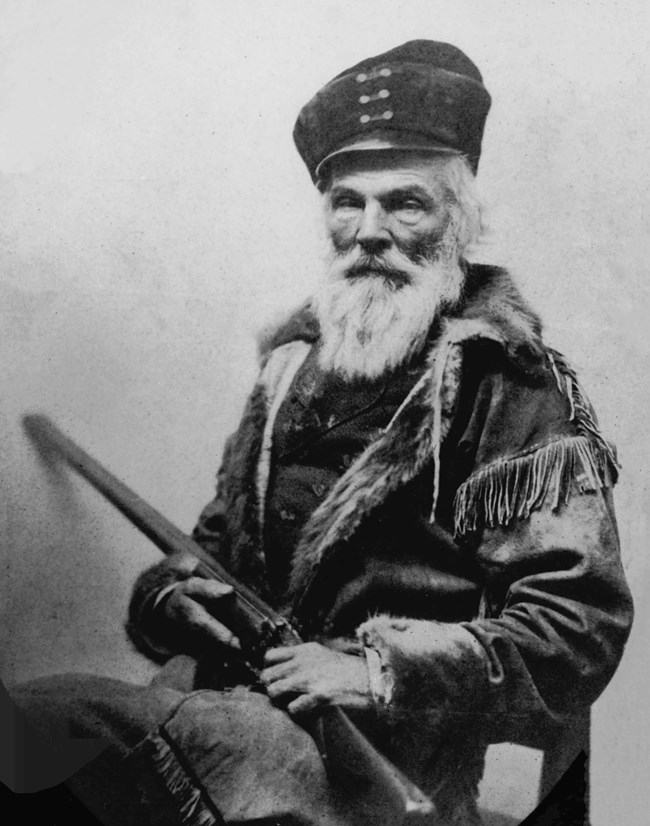

An 1843 emigrant party of about 17 emigrant men, women, and children, led by famed mountain man Joseph R. Walker, hoped to get their eight wagons through the Sierra Nevada and into the California interior. Theirs would be the second wagon train to attempt the feat.

The party made it to the Humboldt Sink (southwest of present-day Lovelock, Nevada) around October 22, short on food and a little hungry but not yet in desperate trouble. They waited there about a week to rendezvous with outriders who were supposed to bring supplies, but those riders, delayed by troubles of their own, never appeared. The little wagon train broke camp and followed Walker south along a trapper’s trail—not a wagon trail—he had traveled on horseback some nine years previous.

The route took them many miles south to Owens Lake, a large pool of brackish water located between today’s Death Valley and Sequoia national parks. With their draft animals giving out, and half-starved themselves, the emigrants abandoned their wagons and continued south on horseback around the south end of the Sierra Nevada range. On December 3 they easily summited the low divide now called Walker Pass, descended to San Joaquin Valley, and followed their pilot toward a hospitable spot he recalled visiting years earlier in the Southern Coast Range. There, at Peachtree Valley, they “passed from famine to feast” (according to California Trail historian George E. Stewart) and spent a joyful Christmas Day dining on the “finest haunches of venison.” While there, they also replenished their food stores by hunting the wild horses that roamed the area.

Walker’s party reached the settlements on the Salinas River shortly after New Year 1844. His emigrants were unable to get their wagons to interior California, but the Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party that same year would wrest vehicles up the Truckee River and over a pass that soon would be named for the Donner Party.

For further reading:

- Breen, Patrick. 1963. Diary. In, Overland in 1846: Diaries and Letters of the California-Oregon Trail, pp. 306-322. Dale Morgan, ed. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London.

- James H.L. 2011. Bruff’s Wake: J. Goldsborough Bruff & the California Gold Rush, 1849-1851. Oregon-California Trails Association, Independence, Mo.

- Koenig, George. 1974, The Lost Death Valley ‘49er Journal of Louis Nusbaumer. Death Valley ‘49ers Inc., Death Valley, Calif.

- McGlashan, C.F. 1902. History of the Donner Party. A Tragedy of the Sierra. 7th Ed. H. S. Crocker Co., Sacramento, Cal. Available free online from Internet Archive.

- Manly, William. 1949. Death Valley in ’49. Borden Publishing, Los Angeles, Calif.

- Murphy, Virginia Reed. 1998. Across the Plains in the Donner Party: A Personal Narrative of the Overland Trip to California. Ye Galleon Press, Fairfield, Wash.

- Stewart, George E. 1962. The California Trail: An Epic with Many Heroes. McGraw Hill, New York, Toronto, and London.

- Werner, Emmy E. 1995. Pioneer Children on the Journey West. Westview Press, Boulder, Col.