Last updated: August 8, 2025

Article

Guardians of the Desert Skies: Tracking Landbird Populations in the Chihuahuan Desert Network

NPS

Overview

In the heart of the American Southwest, the Chihuahuan Desert's rugged beauty hides a vibrant world of songbirds, flycatchers, and warblers. The Chihuahuan Desert Inventory and Monitoring Network (Chihuahuan Desert Network), a team of researchers in the National Park Service, has come to understand that birds, though often overlooked, serve as key indicators of ecosystem health.

Clockwise from top left are black-throated sparrow, verdin, pyrrhuloxia, and ash-throated flycatcher.

Report by NPS / Images © R. Shantz

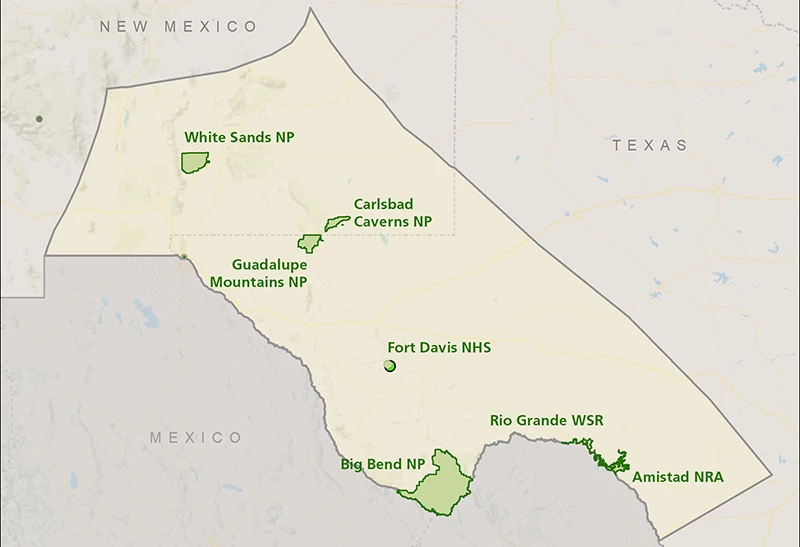

From 2010 to 2017, we monitored landbirds in collaboration with the Sonoran Desert and Southern Plains networks in seven national parks in the Chihuahuan Desert:

- Big Bend National Park

- Carlsbad Caverns National Park

- Guadalupe Mountains National Park

- White Sands National Park

- Fort Davis National Historic Site

- Amistad National Recreation Area

- Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River

Our findings are now in a report that offers valuable insights into the region’s bird communities and shows the importance of long-term monitoring.

Why We Monitor Landbirds

Landbirds play a unique role in the desert. They have high metabolisms, diverse feeding behaviors, and strong ties to specific habitats, making them early warning systems for environmental change. We focus on landbirds because they react quickly to any shifts in their environment and are relatively easy to observe.

Their population sizes, locations, and behaviors give us clues about the health of their habitats. Our monitoring program was created not just to count birds, but to understand how bird populations and communities change over time and what that tells us about the ecosystems they live in. This information helps land managers make informed conservation decisions

© R. Shantz

Monitoring Across a Varied Landscape

In the U.S., the Chihuahuan Desert covers a broad swath of southern New Mexico and western Texas. The seven Chihuahuan Desert Network parks reflect the great diversity of ecosystems in this area, including mountain ranges, grasslands, riparian corridors, and even gypsum dune fields. This ecological variety provides an ideal natural laboratory for understanding how birds respond to different environmental conditions.

To keep things consistent across these contrasting habitats, we used a method called Generalized Random-Tessellation Stratified sampling design. This method helped us choose random survey points that were evenly spaced. It is a type of stratified random sampling, where survey sites are grouped by habitat type and sampled independently. This ensures that each habitat is represented proportionally in the monitoring data.

However, at Fort Davis National Historic Site, we used a systematic grid instead because the park is very small. Also, in riparian habitats (areas adjacent to streams, rivers, or lakes) in Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains national parks, we visited the survey points twice per year for better coverage over time.

Each habitat—whether rugged canyon, desert wash, or wide-open plain—required careful planning to ensure that our surveys captured representative and repeatable data.

NPS

Surveying the Desert Sky

We surveyed for birds in upland and riparian areas in Chihuahuan Desert Network parks every April through June from 2010 to 2017. Using point-count surveys, field scientists recorded every bird seen or heard during a set amount of time at each point. Our goal was to get the following information:

- Species richness—how many species were present

- Occupancy—where each species was found in the parks

- Density—how many individuals of a species occurred per unit of area.

Over the seven years, we collected data on 104 well-surveyed breeding bird species, some of which were found in both riparian and upland habitats. We had enough data to estimate occupancy for 50 species in uplands habitats and 58 species in riparian habitats. We also estimated density for 30 species in uplands and 11 species in riparian areas. Using our data, we developed 52 “species accounts” that detail occupancy and density by habitat and park. This detailed information helps park biologists and regional planners focus conservation efforts where they are most needed.

Focus on Species of Conservation Concern

As part of our monitoring effort, we looked at the presence, distribution, and trends of birds of conservation concern that breed in Chihuahuan Desert Network parks. Out of the 23 breeding bird species of conservation concern, we gathered enough information to create species accounts for seven species:

- Bell’s vireo—listed as state-threatened in New Mexico

- Black-chinned sparrow—listed on the continental watch list

- Cactus wren—a species of regional concern due to habitat loss

- Cassin’s sparrow—declining grassland species

- Loggerhead shrike—showing declines across much of its range

- Lucy’s warbler—a riparian species of concern

- Scott’s oriole—limited to specific upland habitats

NPS/Cookie Ballou

Riparian Corridors: Strongholds of Avian Diversity

After analyzing the data, we found that riparian habitats consistently had greater bird diversity than upland areas. This result was particularly pronounced at Amistad National Recreation Area and Big Bend National Park. Riparian species in these parks also came from a broader range of habitat guilds, including woodland and riparian specialists.

These results highlight the need to protect and restore riparian habitats throughout the Southwest. These green corridors act as lifelines in the dry desert, providing shelter, nesting areas, food, and water. Even narrow or fragmented corridors support diverse landbird communities, reinforcing their importance in regional conservation planning.

Park-Specific Highlights

Each Chihuahuan Desert Network park had unique contributions to regional bird diversity:

- Big Bend National Park had high species richness in both upland and riparian habitats. The park's size and elevation range supported both desert and mountain bird species.

- Carlsbad Caverns National Park had moderate species richness in the uplands. There is potential to expand riparian surveys in this park.

- Guadalupe Mountains National Park riparian areas had high occupancy rates of forest-edge species like western tanager.

- White Sands National Park upland surveys showed consistent populations of specialists like black-throated sparrow, despite harsh conditions at this park.

- Fort Davis National Historic Site, though small, supported stable populations of Bewick’s wren and canyon towhee in the upland grassland habitat.

- Amistad National Recreation Area had the most consistently high-diversity riparian site of the seven parks, especially in years with favorable water conditions.

- Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River has limited data compared to other parks but bird surveys confirmed that a large number of birds are using the river corridor.

© R. Shantz

Challenges and Recommendations

Long-term monitoring has its challenges. Some of the main difficulties include

- Rare species: Detecting changes in occupancy or density for bird species that occur at only a few sites or in low numbers may require decades of data.

- Survey timing: Our broad seasonal window (late March to late June) may mean that some of our observations were of migratory birds that were not actually breeding in the parks.

- Sampling design: Fewer transects in smaller parks limit our confidence in the results because of limited statistical power.

To address these issues, we recommend

- Narrowing the seasonal window to late April through early June to better target breeding species.

- Reallocating effort by increasing the number of transects while reducing the number of points per transect, allowing for broader spatial coverage.

- Prioritizing high-potential sites such as riparian zones in smaller parks like Fort Davis National Historic Site and the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River.

The Long View: Trends Over Time

Using a technique called power analysis, we estimated how long it would take to detect trends with our current survey methods. For common, widespread species, it would take 15 to 30 years to detect a 3% annual decline in occupancy. However, for relatively rare species, it may take over 40 years.

Despite this, the Chihuahuan Desert Network bird monitoring program offers one of the best opportunities to observe gradual, landscape-level changes. Long-term data are essential for telling the difference between natural variability and true population shifts. The landbird report provides a roadmap for future efforts.

© R. Shantz

Moving Forward

Our monitoring work in Chihuahuan Desert Network parks shows the power of consistent, science-based observation. Long-term monitoring connects the ecological dots across a diverse desert landscape, giving us the tools to respond proactively to threats and protect these parks for future generations. Although we have paused landbird monitoring since 2017, we are exploring new methods to continue this important work. One promising approach is the use of passive acoustic recording devices, which can capture bird songs and calls over long periods. These methods are still in development, but they hold great potential for future monitoring efforts.

As landscape and environmental changes continue to reshape the desert, the birds of the Chihuahuan Desert remain both sentinels and survivors. Their songs are more than pleasant background sounds—they are evidence, insight, and a call to environmental stewardship.

For More Information

Colbaugh, J., R. A. Gitzen, P. Valentine-Darby, G. Levandoski, and M. A. Powell. 2024. Landbird Monitoring in the Chihuahuan Desert Network: 2010–2017 synthesis report. Natural Resource Report NPS/CHDN/NRR—2024/2643. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. https:doi.org/10.36967/2307228

Tags

- amistad national recreation area

- big bend national park

- carlsbad caverns national park

- fort davis national historic site

- guadalupe mountains national park

- rio grande wild & scenic river

- white sands national park

- chihuahuan desert network

- chdn

- landbirds

- landbird monitoring

- birds

- bird monitoring

- ecology

- texas

- new mexico