Last updated: December 29, 2021

Article

Cavalry sergeant Harmon Bloodgood: The only regular army Civil War solider buried at St. Paul's

Civil War Soldier Buried at St. Paul’s served with the Third Cavalry of the United States Army

Harmon Bloodgood is the only Civil War veteran buried in the historic cemetery at St. Paul’s who served in the regular United States Army, distinct from the state volunteer regiments created to meet the crisis of the Union. Ten months before Southern batteries pummeled Fort Sumter in South Carolina signaling the onset of the Civil War, Bloodgood joined the cavalry.

He enlisted in June 1860 for a five year tour in the First Mounted Rifles, which had been founded in 1846. The regiment was posted on the broad stretch of the southwest, New Mexico and Texas, fighting the Comanche and other Indian nations. Policing the western frontier of American settlement was the principal responsibility of the regular American army, a small force of about 16,000 soldiers.

Recruits were primarily recent immigrants, mostly from Ireland and Germany. Bloodgood, 21, reflects another channel to the regular army: young men born in America, struggling with difficult circumstances, seeking consistent livelihood and adventure. He was one of five children of a laborer living in Monmouth County, New Jersey. Bloodgood’s enlistment reports an occupation of mason. The recession and reduction in employment in the Northern states caused by the panic 1857 may have contributed to his decision to join the army.

He enrolled in New York City under an alias, Harry Black, perhaps an indication of a strategic decision to conceal identity, a feasible practice in the 19th century before a national classification system. An alias might obscure an ethnic association that the enlistee feared could jeopardize his chances of acceptance, or exaggerate the age of a young recruit. In isolated cases an assumed name masked a criminal background. Yet, there is nothing in Bloodgood’s profile to suggest that the decision was anything more than an intention to devise a simpler, less intimidating name than Bloodgood.

Bloodgood’s (Black’s) regiment was reconstituted as the Third Untied States Cavalry in August 1861, a titular shift; but, like all regular army units, they endured significant changes in personnel and unit cohesion because of secession. More than 300 Army officers resigned commissions when their Southern states withdrew from the Union, joining the fledgling Confederate army. Bloodgood’s cavalry lost 13 officers, or a third of its total, notably its experienced commander, Colonel William Wing Loring. The North Carolinian left on May 13, 1861, claiming: “The South is my home, and I am going to throw up my commission and shall join the Southern Army, and each of you can do as you think best.”

By then, the Union army was accepting thousands of recruits into the volunteer regiments organized by states in response to President Lincoln’s call for a military campaign to sustain the republic. Those newly designated units symbolized and dominated the Union army, fighting the major battles against the Southern forces over the next four years. The regular army retained a separate identity. Often embracing an intuitive understanding of superiority to the state regiments, regular units were generally characterized by tighter discipline, more traditional procedures of chain of command, and greater standardization of uniforms and equipment. Additionally, recruited as a national force rather than from a section of a state, the regulars represented broader geographic and ethnic diversity. They constituted approximately three percent of the total American force. Among these was Private Bloodgood who likely struck an impressive pose in Company D, Third U.S. Cavalry -- sitting erect in the saddle at 5’ 9”, steel saber glistening in the desert sun, grey eyes set below light hair looking out from under the blue hat visor over the parched Southwestern terrain.

Company D fought in two of the important engagements in the trans-Mississippi theater in 1862, part of a campaign by the Confederates to gain territory and valuable minerals by securing the Southwest. One of these was the Battle of Valverde, from February 20 to February 21. A Southern army under Brigadier General Henry Sibley marched west from Texas into the New Mexico territory and registered a tactical victory over a Union force led by Colonel Edward Canby. The American army combined regular cavalry and infantry, along with volunteers and militia from New Mexico and Colorado. One of 3,000 American soldiers in the struggle, Bloodgood’s role is difficult to determine.

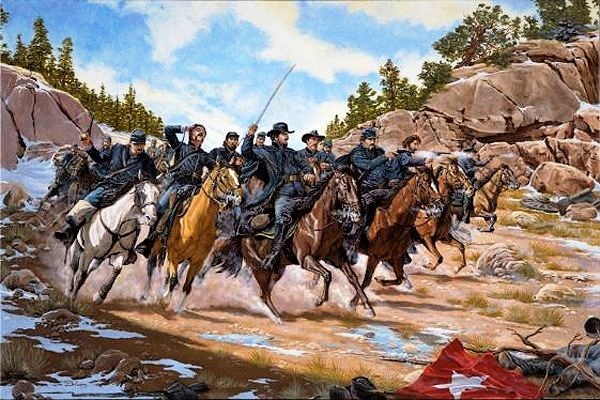

The next engagement in that Confederate offensive transpired at the Battle of Glorietta Pass, fought from March 26 to 28. Sometimes called the “Gettysburg of the West,” the battle in the northern New Mexico territory was the decisive action of the Southwestern region. The Southern army attacked in an effort to break Union possession of the territory Cavalry soldiers of the regular United States Army during the Civil War. along the base of the Rocky Mountains. The regular cavalry repulsed a Southern charge on the encounter’s first day, capturing about 70 Confederates soldiers. Hours of intense combat on March 28 left the Texans in possession of the field. But more strategically vital, Union troops reached the rear of the enemy position and destroyed the Southern supply wagons and drove off the horses and mules. This action, depriving the Southerners of the material resources of war, effectively halted the Confederates’ momentum. Two weeks later, the beleaguered Texans retreated back into the Lone Star State.

The available log of Bloodgood’s service for the remainder of the conflict reveals a capable soldier removed from the major theatres of the Civil War. The Third Cavalry served in Missouri and Tennessee, with no mention of Bloodgood. But he peaks into the historical record as a corporal, Company K, by late 1864, when the unit was stationed in Little Rock, Arkansas. In that Confederate state, the regiment prevented the organization of rebel units, suppressed guerilla bands, and escorted supply trains. The large territory under the cavalry’s jurisdiction required constant scouting in small detachments, which involved hard riding and risk, but no engagements of sufficient magnitude to attract attention.

He had earned a third stripe as a sergeant by November when he was assigned to a detail, or a special unit, charged with erecting winter quarters. A final note in a dutiful soldier’s tenure records his attachment to an ambulance corps in mid April, 1865. Bloodgood’s honorable discharge in Little Rock on June 25, 1865, completing his five year commitment, corresponded with the release from military service of most soldiers from the voluntary regiments.

Bloodgood returned to his native state of New Jersey. He also re-established his antebellum practice of masonry, gaining employment through the surge in construction and infrastructure projects around metropolitan New York City following the Civil War. Certainly, along with thousands of other veterans, he realized the satisfaction of having helped sustain the Union. Bloodgood resided in Jersey City with his wife Mary Jane Carter. They raised several children to maturity, but endured the tragic death of two very young girls. One of those children, Georgiana, who died at age four months in 1887, was the first of the family interred at the St. Paul’s cemetery. Another girl named Georgiana died in 1891 after living only a year and three months, followed by burial alongside her sister. While no surviving records document the reasons for these unfortunate losses, leading causes of early childhood death were diphtheria, tuberculosis and pneumonia. The girls were interred in a plot owned Masonry steeple erected atop St. Paul's Church, late 1880s. by the Carter family, indicating their mother’s connection to St. Paul’s.

The cavalry veteran’s attendance at the girls’ funeral services represented his first visit to St. Paul’s. But he probably maintained an additional connection to the church through his trade as a mason. Interestingly, the only confirmation of a local residence by Bloodgood emerges in the late 1880s, when the City Directory and census captured him living in a boarding house on Mt. Vernon Avenue, two miles from St. Paul’s. This location is blocks from a station on the Harlem line railroad, facilitating a journey of about 30 minutes into Manhattan, followed by a ferry ride across the Hudson River to Jersey City, a total trip of less than two hours.

More importantly, the time period overlaps with a pair of substantial masonry projects at St. Paul’s. These initiatives commemorated the 100th anniversary of the first service (1788) held at the church following the Revolutionary War. Supported through a considerable financial gift of $3,000 (about $80,000 today) from a wealthy widow, the parish exchanged an aging wooden cupola with the impressive stone and brick steeple visible today. Additionally, workers disassembled the wooden horse shed erected in the 1830s and constructed a rectangular masonry carriage house, which forms the basis of the museum building at St. Paul’s. These projects required considerable labor from experienced masons, and Bloodgood apparently worked on these capital improvements. Living at the boardinghouse on Mt. Vernon Avenue accommodated masonry at St. Paul’s and sporadic journeys to visit his wife and children in New Jersey.

An 1898 directory lists Bloodgood living in Brooklyn, another temporary residence to fulfill a short term masonry assignment not far from his home in New Jersey. Mary Jane passed in 1908, followed by interment at St. Paul’s near her daughters. After his wife’s death, the former sergeant moved to Maine, living at the Togus soldiers’ home in Chelsea. He died there of heart failure, on April 29, 1912, at age 72. His daughter Martha arranged to have the coffin bearing his remains interred at St. Paul’s. A soldiers’ stone marks the grave.