Last updated: September 22, 2022

Article

The Thin Line Between Freedom and Slavery: The Story of Catherine "Kitty" Payne

Application for Kitty Payne Site/Rappahannock County Jail.

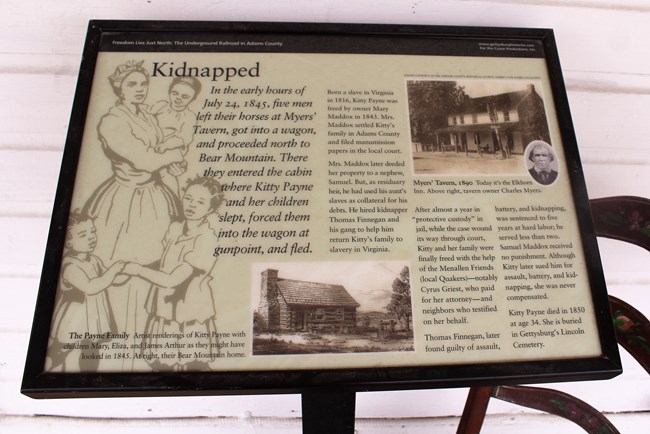

The line between freedom and slavery in antebellum Gettysburg was remarkably thin. Slaveholders frequently crossed the border in pursuit of freedom seekers and free people of color who could pass as fugitives. Catherine “Kitty” Payne and her children Eliza, Mary, and James were a legally emancipated family living in Adams County, Pennsylvania, when Samuel Maddox, Jr., had them seized as slaves in July 1845.

Catherine Payne began her life in Rappahannock County, Virginia. Her father was not a doting parent or loving partner to her enslaved mother: he was an enslaver.[1] The elder Samuel Maddox owned Payne until his death in 1837, when she passed to his “beloved wife Mary Maddox… to do and use as she may see proper during her natural life.”[2] Neither Maddox considered Payne’s husband, Robert, when they filed Samuel’s final will and testament. Robert, a free black man, had to hope that Mary would not sell Catherine or their future children beyond his reach.

Both Robert and Catherine were in luck. On February 25, 1843, Mary Maddox emancipated “Ben aged fifty three, James aged thirty seven, Kitty aged twenty seven, Eliza Jane aged five years, Mary aged four years, [James] Arthur aged two years and George aged two months.”[3] There was one problem: Virginia law prohibited freed enslaved peoples from remaining in the state for more than a year after their manumission. Maddox had to take Payne and her children to Adams County to ensure their continued freedom. She escorted them to Fairfield in May 1843 and lived with them in a rented home until 1844. Robert and little George died shortly thereafter. Before Maddox left, she filed additional documents of emancipation. In a celebration of freedom, Payne moved her family to Menallen Township.[4]

stands in front of the Elkhorn Tavern in Bendersville, PA, describing the ordeal faced

by Catherine Payne and her children.

NPS Photo

It did not last. In May 1843, Samuel Maddox, Jr., argued in court that his aunt intended “to carry the said slaves out of the Commonwealth of Virginia for the purpose of denying your orator of the interest in the said slaves visited in him by the said will” of Samuel Maddox.[5] The court’s failure to appease Maddox ended in treachery. On July 25, 1845, Maddox and a group of men crept into Menallen to kidnap Payne’s family. The men—including the “somewhat noted Thomas Finnegan,” a Hagerstown slave catcher—attacked the Paynes in the middle of the night and forced them into a covered wagon.[6] The youngest child, James, was only four or five years old.[7]

Local Quakers in Menallen Township rushed to Payne’s defense when they learned of her plight. John Wright mounted an unsuccessful rescue that ended on Maryland’s border. When he returned, Cyrus Griest gave $100—$3,373.61 in today’s money—to Yardley Taylor of Rappahannock County, Virginia, to hire a lawyer for Payne.[8] He secured the services of Zephaniah Turner, who agreed “[that] the petitioners [were] entitled to their freedom.”[9] Men like Griest and Taylor amplified Payne’s voice and helped her fight back in a hostile Virginia court.

Payne filed two complaints against Maddox for illegal detainment in August and September. The Rappahannock County Court saw “no reason to deny its interference” and ordered “the clerk to issue process against Samuel Maddox, to appear & answer the said Kitty.”[10] Authorities in Pennsylvania also arrested Finnegan the following year. In both cases, “the principal legal issue debated at the trial was whether Mary Maddox could free the Paynes—whether she had received an absolute estate in the slaves or as estate for life only.”[11] If Mary Maddox had an “estate for life only,” her nephew could legally enslave the Paynes, vindicating Finnegan. Thankfully, the jury in Pennsylvania agreed that Maddox had an absolute estate and sentenced Finnegan to five years in solitary confinement, although he was pardoned after a year and a half.[12]

NPS Photo

Payne continued her prolonged fight in Virginia. Judge Field ruled she could “sue [Samuel Maddox] in a court of equity but not in a court of law” because Mary had never been executrix of her husband’s estate.[13] Despite ruling against Payne, Field also concluded that Mary had an absolute estate. By posting a five-hundred-dollar bond, she could become executrix and free Payne’s family. An increasingly debt-ridden Maddox, realizing the futility of his situation, “rose in open court, and renounced all title to the Slaves” when Field declared his decision “a mere technical objection.”[14] A second trial in a court of equity was not necessary. Mary Maddox marched into the Rappahannock County Courthouse, posted bond, and made herself executrix.[15] Samuel Maddox, Jr.’s, case against Kitty Payne was officially moot.

Payne began her northward trek in late 1846. She married Abraham Brian/O’Brian, a widowed landholder, in 1847 and settled in Gettysburg as his wife. She gave birth to a daughter, Frances, and raised her with Brian’s children. Eliza, James, and Mary lived in separate households, perhaps at Brian’s request. Their mother died in 1850 or 1851. She had been a free woman for four or five years.[16]

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Payne died at the much too young age of 33 or 34 in

August 1850.

Photograph from findagrave.com

Payne’s children guarded their precarious freedoms. Her eldest daughter, Eliza, lived in Gettysburg until 1869. She hid during the battle to avoid shot, shell, and abduction by Confederate forces. Young Frances vacated Gettysburg with her father and stepmother, Elizabeth Brian. She survived the battle and married William Henry Henson, an enslaved man who escaped from the Confederate army. James, ever the adventurer, joined the 27th United States Colored Troops and renewed his mother’s fight for freedom on the battlefield. The children of Catherine Payne wanted better for themselves and their race—they would not succumb to slavery again.[17]

Catherine Payne's story is memorialized by this wayside on the courthouse complex grounds facing the Rappahannock County Jail. The "Kitty Payne Site, Rappahannock County Jail" is a site on the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

Acknowledgement: Thank you to local historian, Debra Sandoe McCauslin, for sharing her collection of documents and photographs. We hope you are able to hear Payne’s voice through the ages.