Last updated: October 10, 2024

Article

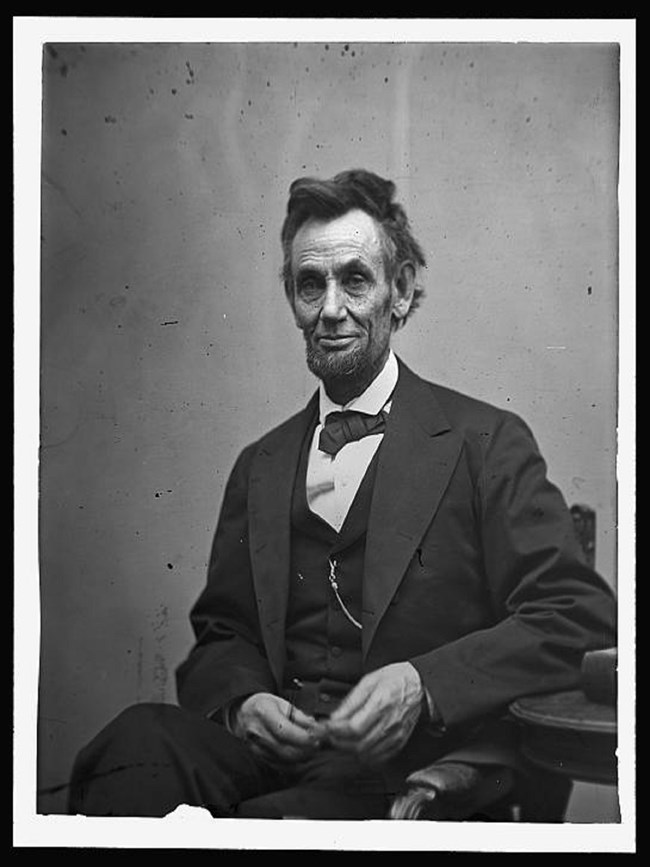

Carl Sandburg and Abraham Lincoln

As a boy in Galesburg, Illinois, Carl Sandburg often heard stories from those who recalled Abraham Lincoln. He often took a shortcut through nearby Knox College. There, on October 7, 1858, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas met for the fifth joint debate in the famous Senatorial contest. Sandburg served in the 6th Illinois Volunteers during the Spanish-American War. During the war, Sandburg served in Puerto Ricco, assigned to General Nelson A. Miles. General Miles was a brigadier general in some of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War in the Army of the Potomac in 1864. The experiences from Sandburg’s childhood and young adulthood sparked his interest in Abraham Lincoln. His first writing on Lincoln appeared in the Milwaukee Daily News in 1909 while working as a reporter. He wrote a short piece describing the use of Lincoln’s face on pennies. In it, he articulated Lincoln’s belief in the common man. Sandburg wrote that it was appropriate that the face of “Honest Abe” appear on the common coin.

“The common, homely face of “Honest Abe” will look good on the penny, the coin of the common folk from whom he came and to whom he belongs.” – Carl Sandburg, Milwaukee Daily News 1909.

Sandburg often felt that he was fortunate to grow up in an area with so much Lincoln history. Sandburg had the idea that he would write a children's biography of Abraham Lincoln that would give children the chance to learn as he did. But the book for young people changed while he wrote. Starting in 1923 and published in 1925, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years had grown into a two-volume 344,000-word study. The volumes covered Lincoln’s life up to his move from Springfield to Washington to become the President of the United States. The Preface to the Prairie Years covered the rest of Lincoln’s four years before his assassination.

Sandburg had planned to stop writing about Lincoln after the publication of The Prairie Years. But Sandburg was so caught up in the stories of Lincoln that he found it difficult to stop. Sandburg became engaged in Lincoln’s history and for the next 13 years, he wrote about the President’s last four years. His research was extensive. He met with historians, collectors, librarians, and children of those who played a part in the Civil War era. He spent time in the White House researching Lincoln. He read newspapers from the United States and the Confederacy from that period. He read more than 1,000 books in his first year of research alone. Finally, in 1939 Sandburg published the four-volume Pulitzer-Prize-winning Abraham Lincoln: The War Years. In a Time magazine article, it was written,

“This four-volume biography… is a work whose meaning will not soon be exhausted, whose greatness will not soon be estimated. It can be said that no U.S. biography surpasses it in wealth of documentation and fidelity to fact, that none, not even Douglas Southall Freeman’s monumental Robert E. Lee, can compare with it in strength, scope and beauty…”

Still, Sandburg did not stop writing about Lincoln after publishing The War Years. He continued to study Lincoln even after he moved to North Carolina in 1945. In 1954 Sandburg published an abridged one-volume edition of Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and The War Years. Sandburg referred to this edition as "distilled." Due to the amount of information in the six volumes, Sandburg said the series was, “harder to un-write, than to write.” The complete publication led Sandburg to become an authority on Lincoln. He built a reputation traveling across the nation lecturing to colleges and universities on Lincoln. In 1959, Sandburg was asked to speak to a joint session of Congress on the 150th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Lincoln, making him one of the very few private citizens to ever hold such an honor.

Library of Congress

FEBRUARY 12, 1959

Not often in the story of mankind does a man arrive on earth who is both steel and velvet, who is as hard as rock and soft as drifting fog, who holds in his heart and mind the paradox of terrible storm and peace unspeakable and perfect. Here and there across centuries come reports of men alleged to have these contrasts. And the incomparable Abraham Lincoln born150 years ago this day, is an approach if not a perfect realization of this character. In the time of the April lilacs in the year 1865, on his death, on the casket with his body was carried north and west a thousand miles; and the American people wept as never before; bells sobbed, cities wore crepe; people stood in tears and with hats off as the railroad burial car paused in the leading cities of seven states ending its journey at Springfield, Illinois, the hometown. During the four years he was President he at times, especially in the first three months, took to himself the powers of a dictator; he commanded the most powerful army still then assembled in modern warfare; he enforced conscription of soldiers for the first time in American History; under imperative necessity he abolished the right of habeus corpus; he directed politically and spiritually the wild, massive, turbulent forces let loose in Civil War. He argued and pleaded for compensated emancipation of the slaves. The slaves were property, they were on the tax books along with horses and cattle, the valuation of each slave next to his name on the tax assessor‘s books. Failing to get action on compensated emancipation, as a Chief Executive having war powers he issued the paper by which he declared the slaves to be free under "military necessity." In the end, nearly $4,000,000 worth of property was taken away from those who were legal owners of it, property confiscated, wiped out as by fire and turned to ashes, at his instigation and executive direction. Chattel property recognized and lawful for 300 years was expropriated, seized without payment.

In the month the war began, he told his secretary, John Hay, ―"My policy is to have no policy" Three years later in a letter to a Kentucky friend made public, he confessed plainly, "I have been controlled by events." His words at Gettysburg were sacred, yet strange with a color of the familiar: "We cannot consecrate – we cannot hallow – this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far beyond our poor power to add or detract" He could have said "The brave union men." Did he have a purpose in omitting the word "union?" Was he keeping himself and his utterance clear of the passion that would not be good to look back on when the time came for peace and reconciliation? Did he mean to leave an implication that there were brave Union men and brave Confederate men, living and dead, who had struggled there? We do not know, of a certainty. Was he thinking of the Kentucky father whose two sons died in battle, one in Union blue, the other in Confederate gray, the father inscribing on the stone over their double grave, "God knows which was right?" We do not know. His changing policies from time to time aimed at saving the Union. In the end his armies won and his nation became a world power. In August of 1864, he wrote a memorandum that he expected to lose the next November election; sudden military victory brought the tide his way; the vote was 2,200,000 for him and 1,800,000 against him. Among his bitter opponents were such figures as Samuel F. B. Morse, inventor of the telegraph, and Cyrus H. McCormick, inventor of the farm reaper. In all its essential propositions the Southern Confederacy had the moral support of powerful, respectable elements throughout the north, probably more than a million voters believing in the justice of the Southern cause. While the war winds howled he insisted that the Mississippi was one river meant to belong to one country, that railroad connection from coast to coast must be pushed through and the Union Pacific Railroad a reality. While the luck of war wavered and broke and came again, as generals failed and campaigns were lost, he held enough forces of the Union together to raise new armies and supply them, until generals were found who made war as victorious war has always been made, with terror, frightfulness, destruction, and on both sides, north and south, valor and sacrifice past words of man to tell. In the mixed shame and blame of the immense wrongs of two crashing civilizations, often with nothing to say, he said nothing, slept not at all, and on occasions he was seen to weep in a way that made weeping appropriate, decent, majestic. As he rode alone on horseback near soldiers home on the edge of Washington one night his hat was shot off; a son he loved died as he watched at the bed; his wife was accused of betraying information to the enemy, until denials from him were necessary. An Indiana man at the White House heard him say, "Voorhees, don‘t it seem strange to you that I, who could never so much as cut off the head of a chicken, should be elected, or selected, into the midst of all this blood?" He tried to guide general Nathaniel Prentiss Banks, a Democrat, three times Governor of Massachusetts, in the governing of some 17 of the 48 parishes of Louisiana controlled by the Union armies, an area holding a fourth of the slaves of Louisiana. He would like to see the state recognize the Emancipation Proclamation, "And while she is at it, I think it would not be objectionable for her to adopt some practical system by which the two races could gradually live themselves out of their old relation to each other, and both come out better prepared for the new. Education for the young blacks should be included in the plan." To Governor Michel Hahn elected in 1864 by a majority of the 11,000 white male voters who had taken the oath of allegiance to the Union, Lincoln wrote, "Now that you are about to have a convention which, among other things, will probably define the elective franchise, I barely suggest for your private consideration, whether some of the colored people may not be let in – as for instance, the very intelligent and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks."

Among the million words in the Lincoln utterance record, he interprets himself with a more keen precision than someone else offering to explain him. His simple opening of the house divided speech in 1858 serves for today: "If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending we could better judge what to do, and how to do it." To his Kentucky friend, Joshua F. Speed, he wrote in 1855, "Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation we began by declaring that 'All men are created equal, except Negroes'.‘ When the know-nothings get control, it will read "All men are created equal except Negroes and foreigners and Catholics.' When it comes to this, I shall prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty." Infinitely tender was his word from a White House balcony to a crowd on the White House lawn, "I have not willingly planted a thorn in any man‘s bosom," or a military governor, "I shall do nothing through malice; what I deal with is too vast for malice" He wrote for Congress to read on December 1, 1863, "In times like the present men should utter nothing for which they would not willingly be responsible through time and eternity" Like an ancient psalmist he warned Congress, "Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history. We will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance or insignificance can spare one or another of us.

The fiery trial through which we pass will light us down in honor or dishonor to the latest generation." Wanting Congress to break and forget past traditions his words came keen and flashing. "The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate for the stormy present. We must think anew, we must act anew, we must disenthrall ourselves." They are the sort of words that actuated the mind and will of the men who created and navigated that marvel of the sea, the nautilus, and her voyage from Pearl Harbor and under the North Pole Icecap.

The people of many other countries take Lincoln now for their own. He belongs to them. He stands for decency, honest dealing, plain talk, and funny stories. "Look where he came from—don‘t he know all us strugglers and wasn‘t he a kind of tough struggler all his life right up to the finish?" Something like that you can hear in any nearby neighborhood and across the seas. Millions there are who take him as a personal treasure. He had something they would like to see spread everywhere over the world. Democracy? We can‘t say exactly what it is, but he had it. In his blood and bones he carried it. In the breath of his speeches and writings it is there. Popular government? Republican institutions? Government where the people have the say-so, one way or another telling their elected rulers what they want? He had the idea. It‘s there in the lights and shadows of his personality, a mystery that can be lived but never fully spoken in words.

Our good friend the poet and playwright Mark Van Doren, tells us, "To me, Lincoln seems, in some ways, the most interesting man who ever lived . . . He was gentle but this gentleness was combined with a terrific toughness, an iron strength."

How did he say he would like to be remembered? His beloved friend, Representative Owen Lovejoy of Illinois, had died in May of 1864, and friends wrote to Lincoln and he replied that the pressure of duties kept him from joining them in efforts for a marble monument to Lovejoy. The last sentence of his letter saying, "Let him have the marble monument along with the well assured and more enduring one in the hearts of those who love liberty, unselfishly, for all men." So perhaps we may say that the well assured and most enduring memorial to Lincoln is invisibly there, today, tomorrow and for a long time yet to come in the hearts of lovers of liberty, men and women who understand that wherever there is freedom there have been those who fought and sacrificed for it.