Last updated: June 8, 2023

Article

Carl Sandburg Poetry Collection: Child Labor

Library of Congress

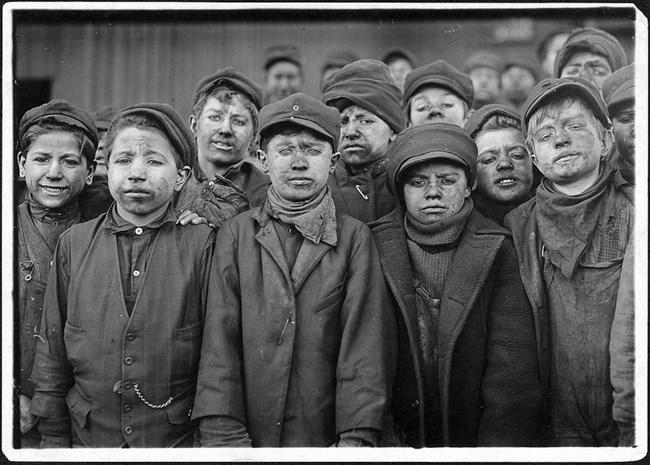

In the early 1900s, Carl Sandburg often wrote about his concerns for workers. Among those workers he concerned himself with were the most vulnerable. Child labor was a hotly debated issue at the time. Even adult workers had almost no protections or rights. Sandburg stood against the abuse of child labor and spoke openly on the issue. In a speech, "The Three Great Crimes of Civilization," Sandburg opened with the subject,

"One of the supreme blunders of modern civilization is that practice ordinarily known as child labor. . . hundreds of thousands of children are at work every day in mines, factories and shops ground down into toil."

Carl Sandburg's life, travels, and work shaped his stances on labor and child labor. Sandburg traveled restlessly in his early adulthood. His travels introduced him to people all over the U.S. and their stories, and their children's stories. In his own childhood Carl dropped out of school after the eighth grade to work and help his family. Sandburg's work as a newspaperman also influenced his impression of childcare. His writing and poetry reflected the power of what he saw, below there are selections from Sandburg's Chicago Poems as examples.

They Will Say

Of my city the worst that men will ever say is this:

You took little children away from the sun and the dew,

And the glimmers that played in the grass under the great sky,

And the reckless rain; you put them between walls

To work, broken and smothered, for bread and wages,

To eat dust in their throats and die empty-hearted

For a little handful of pay on a few Saturday nights.

Mill-Doors

You never come back.

I say good-by when I see you going in the doors,

The hopeless open doors that call and wait

And take you then for – how many cents a day?

How many cents for the sleepy eyes and fingers?

I say good-by because I know they tap your wrists,

In the dark, in the silence, day by day

And all the blood of you drop by drop,

And you are old before you are young.

You never come back.

Child of the Romans

The dago shovelman sits by the railroad track

Eating a noon meal of bread and bologna.

A train whirls by, and men and women at tables

Alive with red roses and yellow jonquils,

Eat steaks running with brown gravy,

Strawberries and cream, éclairs and coffee.

The dago shovelman finishes the dry bread and bologna, Washes it down with a dipper from the water-boy,

And goes back to the second half of ten-hour day’s work

Keeping the road-bed so the roses and jonquils

Shake hardly at all in the cut glass vases

Standing slender on the tables in the dining cars.

Anna Imroth

Cross the hands over the breast here – so.

Straighten the leg a little more – so.

And call for the wagon to come and take her home.

Her mother will cry some and so will her sisters and brothers.

But all of the others got down and they are safe and this is the only

One of the factory girls who wasn’t lucky in making the jump

When the fire broke

It is the hand of God and the lack of fire escapes.

According to Paula Steichen, Sandburg's granddaughter, one poem came from his work with Chicago's Daily News. On assignment in the city, Sandburg "learned that seven times as many children died in the Chicago stockyards district as in nearby Hyde Park." He saw the connection between abused and underpaid worker's and the grief of a district. Even when the abused were adult workers, the children still paid an impossible price. He described the suffering caused by the stockyards' working conditions, in his poem, "The Right to Grief."

The Right to Grief

To Certain Poets About to Die

Take your fill of intimate remorse, perfumed sorrow,

Over the dead child of a millionaire,

And the pity of Death refusing any check on the bank

Which the millionaire might order his secretary to scratch off

And get cashed

Very well,

You for your grief and I for mine

Let me have a sorrow my own if I want to

I shall cry over the dead child of a stockyards hunky

His job is sweeping blood off the floor

He gets a dollar seventy cents a day when he works

And it’s many tubs of blood he shoves out with a broom day by day.

Now his three year old daughter

Is in a white coffin that cost him a week’s wages.

Every Saturday night he will pay the undertaker fifty cents till the debt

is wiped out

The hunky and his wife and the kids

Cry over the pinched face almost at peace in the white box

They remember it was scrawny and ran up high doctor bills

They are glad it is gone for the rest of the family now will have more

to eat and wear

Yet before the majesty of Death they cry around the coffin

And wipe their eyes with red bandanas and sob when the priest says,

''God have mercy on us all ''

I have a light to feel my throat choke about this

You take your grief and I mine— see?

Tomorrow there is no funeral and the hunky goes back to his job sweep-

ing blood off the floor at a dollar seventy cents a day

All he does all day long is keep on shoving hog blood ahead of him with

a broom