Last updated: June 12, 2024

Article

Caring for Mementos left at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

This is a transcript of a presentation at the Preserving U.S. Military Heritage: World War II to the Cold War, June 4-6, 2019, held in Fredericksburg, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of the presentation on YouTube.

Preserving Public Memory: Caring for Mementos left at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Presenter: Janet Folkerts

Abstract

Dedicated in 1982, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial has become known across the country as the place to go to remember and honor those who died in the Vietnam War and to leave a token of remembrance. But what happens to those remembrances that are left behind?

In this presentation, Janet Folkerts, museum curator for the National Mall and Memorial Parks and the staff member charged with caring for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial museum collection, will share how the National Park Service preserves the thousands of items left at the memorial every year. She will outline the history of the collection and the procedures that have been developed to transfer the objects from a public memorial to a state-of-the-art collection storage environment. She will detail the difficulties and questions that arise when taking on a collection of “abandoned” objects – questions such as: how do we establish legal custody of these objects? What is the copyright status? How do we determine what was meant to be left and what wasn’t? What do we do when objects are damaged by the elements?

Finally, this presentation will share a few of the stories from the thousands of objects that have been left at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, including a piece of a Huey helicopter and a bicycle.

National Park Service

Presentation

Janet Folkerts: Okay. Hello, everyone. Thank you for giving me a chance to be here today. My name is Janet Folkerts, like she said, and I work for the National Park Service for the National Mall and Memorial Parks. I actually work for the Division of Cultural Resources. So I'm sorry Alan wherever you are.

Specifically, I'm responsible for the care and preservation of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Museum collection. Can everyone hear me all right?

I've worked with this collection for almost 10 years now and sometimes I take for granted that others would know and understand already what exactly it is and what we do in taking care of it. I'm here today to explain to you what it is and what we do. I'll tell you about this unique collection and share how we at the National Park Service care for these items.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial museum collection is unlike any other museum collection in the world. Considered the first of its kind, the Vietnam collection is comprised entirely of tributes and mementos that are left by visitors at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Every item in the collection, with few very minor exceptions, has been the left somewhere along the Memorial by a visitor or a veteran who has made a trip to The Wall as it is often called. The collection started this way through spontaneous offerings left behind and we continue to honor that tradition. For that reason, we don't accept items received by mail. Every item in the collection is something that is left behind at the Memorial.

We've been contacted in the past by institutions that would like to put together exhibits related to the Vietnam War. So we feel it's important to emphasize that this collection is not a typical history collection. It does not document the history of the Vietnam War. Instead this collection is a social history of the people who served in the war, including those who die and those who survived. The items are directly from veterans themselves, from family members, friends, loved ones. They tell us about their experiences before, during, and after the war. They tell us who they were growing up, how they were either enlisted or drafted into the war, about how they were received, and how they coped with the return to regular life in America.

The National Park Service did not think this collection into existence. There was no planning in anticipation of starting the collection. It began organically and spontaneously from the very first days of the Memorial's existence. When the Memorial was dedicated in November 1982 many items were left behind at the base of the Memorial and continued to be left as more and more people came to see it. The act of deliberately leaving items behind after the visit had never been seen before at any other memorial in the National Mall, possibly because this was the first memorial that was built to honor veterans and individual soldiers instead of politicians or eminent figures. In fact, prior to the dedication of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1982 the latest memorial to be built on the Mall was the Thomas Jefferson Memorial in 1943.

As the items being left were deeply personal and meaningful, the staff collected them and held onto them for the time being until we could figure out what to do with them. As the collection continued to grow and no one came back to claim the items, the National Park Service decided in 1984 to gather them as a museum collection and preserve the mementos alongside other items under the care of our museum management program, including historic objects from Ford's Theater National Historic Site, three local civil war national battlefields, Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial among others.

After it was established, we set up a set of procedures that are still largely in place to this day for how we bring items into the museum collection. This is a very, very quick pictorial overview of the process. Rather than locating a donor, corresponding with them, signing paperwork, and taking in the donation, we essentially just wait for donors to leave their items at the Memorial. The traditional process that other museums go through is not in existence here. Items are left nearly every day by visitors from around the world. At the end of each day, park rangers collect the items and store them in a temporary, covered, secured location. Every week or so I go to the location and retrieve the items and transport them to an isolated room in the collection's storage facility in which I am duty stationed.

A temporary storage was moved from an unregulated corral to a secure temperature-controlled room. Items are sorted immediately upon retrieval and when necessary they're dried and placed in low-oxygen, zero degree freezer in our collection storage building. Damaged or moldy items are no longer accessioned into the museum collection.

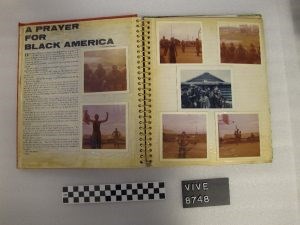

Another common problem with objects from this era is inherent vice. So more modern collections means we have materials including plastics, polyurethane foams, tapes, other adhesives. We have a number of these kind of sticky photo albums in our collection. I believe the common term for them is magnetic photo albums. These types of materials are generally were not made for the long haul and are already starting to degrade very quickly. As you can see, the label attached to this plastic dog figurine is held on by Scotch tape that is already losing its adhesiveness. Things like this, would need conservation in order to help keep them in the original configuration.

There's only so much we can do to combat inherent vice. While every object has some kind of inherent degradability, nothing lasts forever, we now place restrictions on acquiring objects that seem to be near to or already falling apart. For those items that have already been accessioned, we keep them in safe storage environments and limit object handling. When we have the available funds, we also send items for conservation treatment.

Seen here is the treatment of the photo album visible in the last slide, which was conserved in 2015. During conservation treatment, each page of the album was scanned and the photographs and clippings were carefully removed from the damaging adhesive that they were mounted to. The photographs were placed in folders in the original order of their display in the album. The album was disassembled and the damage pages and degrading plastic covering them were discarded. The front and back covers of the album, which contained writing, were kept with photographs.

One question that arose when the National Park Service first began collecting the tributes was do we even have the legal authority to keep these items? That's a good question to ask, I think. Objects are essentially donated to the Memorial and, in essence, to the National Park Service but no transfer document or deed of gift is ever signed. Often we don't know who the original donor of these objects are and there's no way for us to contact them. It's a little unrealistic to try to get deeds of gift for every single object left behind.

Luckily our legal title of the items is established by the Code of Federal Regulations section 102-41.80 which states that "personal property is voluntarily abandoned when the owner of the property intentionally and voluntarily gives up title to such property and title vests in the Government." So essentially by intentionally placing items on federal land at the Memorial donors that are transferring these titles of the objects to our official use, for example, in a museum collection.

Now, just because we have legal title of the objects does not mean that we have the copyright. This is a challenge that we continue to puzzle over and will likely always puzzle over. Original works of literature, photography, and art are covered by our national copyright law. So how do we use these objects for interpretation or exhibits if they're protected by copyright, especially if we don't know who the original donor is or cannot locate them?

In 2015 we made this inquiry to the Office of the Solicitor of the Department of Interior. We got a helpful but somewhat a very legalese memo back to us to help. After review, it said that generally our use of the collection falls under Fair Use law. So when we give access to the collection to researchers, press, or students we have them sign a copyright agreement, letting them know the circumstances of Fair Use. It's the responsibility of the user to ensure that the use of the objects falls under categories listed here or to locate the donor if necessary.

Our final challenge is one that doesn't occur too often, but it's something that we have to continue to be mindful of. Many items, especially from the items that were left in the 1980s and 1990s, include what is considered personally identifiable information. So a major culprit of this are dog tags, which often list social security numbers, and another is letters with full addresses visible. Sometimes, like this one, we even get letters with social security numbers written on them. As you see in the image on the right. Don't worry, the number has been blurred so you can't record it and steal someone's identity. Solutions for this challenge are fairly just common sense. Objects already in the collection that have PII are marked as restricted. PII is blurred or covered when the objects are visible to others and is redacted in the record. We limit acquisitions of sensitive information.

As you can see, the social security number on this dog tag has been blurred. Above it, though, you see the military identification number which is actually public information, available under FOIA, and is a searchable number which is why it's not blurred here. Just like this dog tag, we have to be mindful of every single object that we're showing to people to make sure that there's no sensitive information that we share.

Now after telling you about all these challenges, you might be asking why we continue to collect at all. Once you see the objects in the collection, the answer is really apparent. This unique collection documents not events or famous figures in our history, but the lives of everyday people who fought for our country. These are your neighbors, your friends, grandparents, uncles, schoolmates. Each item tells a story about someone who fought in the Vietnam War and to us, those stories are worth remembering. With the time I have left, I'll share a few of these stories with you.

This object here is known as Buddy's Bike. Buddy was the nickname of Christian Franz Feit, III. According to the letter that's attached to the bicycle, Buddy used this to get around in his home town of Smethport, Pennsylvania. In his youth, he developed a friendship with an older man named Earl who worked in an auto garage and would often help him fix his bicycle. After Buddy turned 16, he upgraded to a Jeep and used his bicycle less, which makes total sense because why use a bike when you have a Jeep? Earl later expressed an interest in purchasing the bicycle for exercise. So, Buddy gave him his old bicycle to Earl free of charge.

Buddy later enlisted in the U.S. Navy after high school and was sent to Vietnam at the end of 1967. Earl happened to pass away that year and the bicycle was kept in his family. Then Buddy was killed in the Battle of the Khe Sanh on January 25th, 1968. The bicycle was kept in Earl's family until 2017 when they decided to return it to Buddy at The Wall. They left it just as you see it here.

The next item is part of a Huey helicopter, tail number 174, it was used during the war. The item is a door panel taken from the side of the helicopter. Just to clarify, we do not have a helicopter in our collection. We have this object that's over here. On the right, you can see the helicopter as it was when it was found in a retired aircraft graveyard in Arizona. The helicopter was discovered and purchased a few years ago by a nonprofit organization called Light Horse Legacy to be used as an art project for veterans struggling with PTSD. In the bottom picture on the right, you can see how it looks now. The veterans art project is called the Take Me Home Huey. The veteran art and artist, Steve Maloney, used the helicopter as his canvas to depict the 60s culture and to show memories of the good things that were missed back home.

Going back to 1969 and the two panels visible here... Well, I guess the one panel, this is both sides of it... Huey number 174 was being used by the 15th Medical Battalion as a Medevac helicopter. On Valentine's Day in 1969 it was en route to pick up wounded soldiers when it received ground fire. It was forced to land and crew member Specialist IV Gary Dubach got off to set up a perimeter. As he was disembarking, he was struck in the head by the main rotor blade and killed. Unfortunately, the same thing happened to Medic Specialist IV Stephen Schumacher when he got out to assist Dubach. Ultimately, the rest of the crew survived and the aircraft was used for further missions.

When the Take Me Home Huey's guys started working on the helicopter, they were actually able to get in contact with the surviving members of the crew from that day over 50 years ago. These men, along with the three sisters of Dubach and Schumacher, were all reunited and visited The Wall on May 28th in 2016 and left this mostly unaltered portion of the helicopter in honor of Dubach and Schumacher. The rest of the helicopter is currently touring the country to promote healing of veterans from all conflicts who suffer from PTSD.

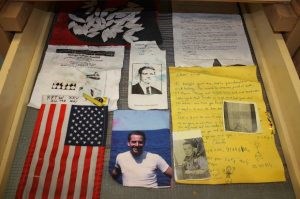

Finally, this is a collection of items that were taken from the body of the North Vietnamese army soldier by an American GI on April 8th, 1969. The NVA soldier was killed during an ambush of Company... by Company A of the 2nd Battalion Mechanized 47th Infantry Regiment in Long An Province. At the end of his tour, the GI carried these items home with him and stored them in his closet for over 42 years. Early in the morning, he visited the Memorial on Veterans Day in 2011. He made the trip to the Memorial to leave the objects behind. In a letter he left with the recovered items, he explains that his motivations for leaving them were a longing for reconciliation and a desire to put the man's soul to rest. He contemplates the life that this man never had and asked for forgiveness from his former enemy.

The recovered items include... Now I'm going to see if I can figure out how to use this thing. There we go.

The recovered item include a National Liberation Front flag here, a silk pennant with Vietnamese text right there. The text roughly translates to "most decent squad." There is a black and white photograph of eight Vietnamese soldiers right here. There are two Vietnamese stamps that commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Russian October Revolution and, of particular interest to us, this item right here is actually a handwritten Vietnamese poem titled The Springs Flowers in Full Bloom. This is just something that someone wrote or drew on graph paper, but it's actually... It's a personal copy of the same poem that was broadcast over Radio Hanoi by Ho Chi Min as a code to start the Tet Offensive.

All of these items were left in a wooden box with Chinese characters lighting the interior. They show the guilt that many veterans carried with them over the years and they show how the Memorial has become a place to put their guilt and their worries to rest. So with that, I would like to thank you all for the opportunity to share this collection with you and to open up for questions.

Mary Striegel: We have questions?

Speaker 1: Thanks, Janet. It was so touching. I mean the power of objects.

Janet Folkerts: Thank you.

Speaker 1: This is what I was thinking the whole time, the power of objects, but what do you do with the things that you don't take? What happens to them?

Janet Folkerts: The things that we don't take are either set aside for destruction or are immediately disposed of. As I was saying in the presentation, these are items that are not really actually connected to a name on The Wall or to any single veteran's experience during the war. These are mostly unpersonalized and just general thank you items and they're immediately disposed of.

Speaker 1: I was also wondering if there was a way to have some sort of thing online that people could fill out because... I don't know, like you say a lot of it doesn't have any context, nobody writes a message. Obviously the bike had some sort of letter with it or something like that.

Janet Folkerts: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Speaker 1: Is there a way to do it? Where you could encourage someone if they wanted to give the story behind the object?

Janet Folkerts: We usually do have... We used to have an online kind of source where people could go to fill out information. We have a web... or a email address as well that people can email, v-i-v-ecurator@nps.gov. But, we also have the park rangers who are working at the site on the time. We never asked them to interrupt anyone at the Memorial. If they meet somebody who is willing or wants to share their experience or the reason why they're leaving the object, we encourage them to write down a story there. But, again, we don't have anyone who you know goes up to people and say, "Well, what are you leaving? Why you're leaving it?" Leaving things at the Memorial is a very personal and kind of private experience for a lot of people. So I always just try to make myself as available as possible for that information to be passed on to me.

Mary Striegel: Okay. We'll have two more questions and then we'll have to move forward.

Speaker 2: So you had mentioned that it's considered a tradition for folks that just leave things or by word of mouth and publications. So are there efforts right now to publicize the revised policies of what's being collected or what won't be collected?

Janet Folkerts: We don't... When we were revising the policy we actually put it online to solicit public comment, which is pretty rare when you're putting out a Scope of Collection Statement, usually that's very much in-house document, but we wanted to share that kind of revision with the public. So we did it at the time, put it online and welcomed public comment on our scope, but we also have our finalized Scope of Collection Statement on our website. So people can go in there and read through to learn what we keep for the collection. But again, we don't discourage people from leaving objects at the Memorial. We just try to make it known as much as possible what will actually become part of the museum collection.

Speaker 3: I think I speak for all of us when I say thank you to you and your staff for doing what you do for this project. So thank you.

Janet Folkerts: Yeah. I'm very happy to do it. It's a very unique collection and I really enjoy working on it.

Mary Striegel: Okay. Thank you.

Speaker Bio

Janet Folkerts has worked for the National Park Service on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial museum collection since 2010 in a variety of positions, including her current role as the museum curator, which she has performed since 2016. Prior to her work with the National Park Service, she served on a team of archeologists from the University of Maryland performing excavations on 18th-century historic sites in Bladensburg, Maryland. She graduated from the University of Maryland in 2009 with a bachelor of arts in archeological anthropology and a major in history.

Read other articles from this symposium, Preserving U.S. Military Heritage World War II to the Cold War, or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.