Last updated: October 19, 2021

Article

Southern Live Oak at Oakland Plantation

A double row of live oak trees, known as an allée, is a character-defining feature of historic plantations in the southern United States. The NPS preserves an iconic example in a cultural landscape in Louisiana. Journey with us back into the history of the cotton plantation that bears these magnificent trees.

Specimen Details

-

Location: Oakland Plantation

-

Species: Southern Live Oak (Quercus virginiana)

-

Landscape Use: Tree Row/Formal Promenade

-

Age: Approximately 200 years (estimated first planting 1820s)

-

Condition: Good

Setting

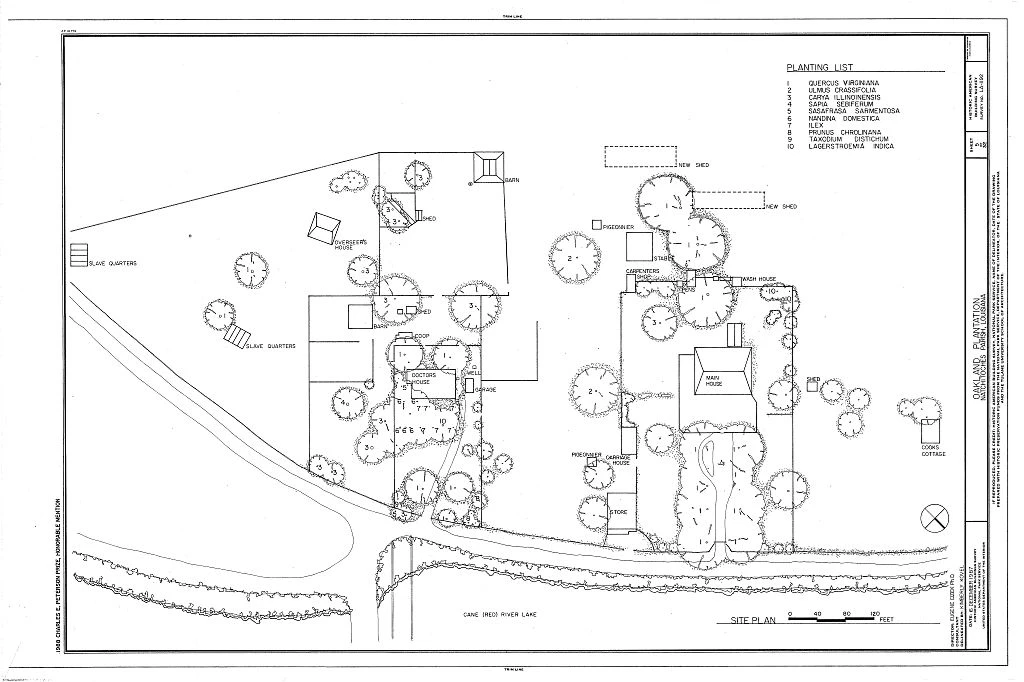

Oakland Plantation is situated in the Cane River Creole National Historical Park, in Natchitoches Parish in northwestern Louisiana. The Park is located in the lower Red River Valley about 100 miles from the river’s junction with the Mississippi. The long human history of the region has been strongly influenced by the operation of its natural systems including the humid subtropical climate, the peculiarities of the river and its floodplain, the fertile soils, and the diverse vegetation and wildlife that made the region their home.The natural vegetation and wildlife of the Cane River region were disturbed and altered over many centuries by the presence of Native American peoples. The region was the home of tribes belonging to the Caddoan linguistic group, in particular the Natchitoches. They practiced agriculture as well as gathering, hunting, and fishing, and they established villages. Although floods have obscured the archaeological record, there is evidence of several village sites in the valley.

The arrival of Europeans led to the establishment in 1714 of the French military post of St. Jean Baptiste. Within a few years of their arrival, the French had developed a village beside their fort. In its scattered layout of homes and clearings it probably resembled the layout of the nearby village of the native Natchitoches, from whom the French appropriated the name for their settlement.

In 1722 the inhabitants of Natchitoches numbered 54, and already the population included enslaved people. There were 28 slaves, of whom 8 were Native Americans and 20 were of African origins. The French colonists found it difficult to enslave the native population, so they turned to the transatlantic slave trade. In 1724 the slave laws, known as the Code Noir, which were already in operation in the West Indies, were introduced to Louisiana. They were to provide the legal framework for the treatment of the enslaved until the end of the Civil War (Ian Firth and Suzanne Turner, Oakland Plantation Cultural Landscape Report Part 1 2003, 9-15).

1850 U.S. Check Plat Map, Approved by Surveyor General R. W. Boyd. Louisiana State Land Office (electronic resource, https://wwwslodms.doa.la.gov/WebForms/DocumentViewer.aspx?docId=526.02804&category=H#1, accessed August 23, 2021)

NPS / Cane River Creole National Historical Park

Significance

The location of the live oak allée is the Emanuel Prud’homme property on the Isle Brevelle. From its establishment in the 1790s until the death of Emanuel’s son Phanor in 1865, this large cotton plantation grew to include over 1900 acres of land on the banks of Cane River, plus another 1500 acres of land in detached parcels. It was operated with an enslaved workforce of about 70 hands, and by 1860 the plantation was home to nearly 150 people of African descent. The business of the plantation was disrupted by the Civil War, and the death of Phanor Prud’homme in 1865 coincided with the end of that war and the emancipation of the enslaved workforce. In 1873, the land was divided between Phanor’s sons, and most of the land on the right-hand bank of the river became Oakland Plantation. This property was to be owned and managed by four more generations of Emanuel Prud’homme’s family until 1997, when its center was acquired by the NPS. The Oakland Unit now comprises approximately 45 acres (Firth and Turner, 6).

Judging by their size and family tradition, the planting of the allée of southern live oaks (Quercus virginiana} occurred in the time of Emanuel Prud’homme. It was probably in the 1820s that the main house was given its formal landscape setting, and the allée leading from the river to the house was planted by enslaved workers. The appearance of the front of the house would have been important in conveying to the public the status of the Prud’homme family. The live oak-lined driveway framed the view of the house and created a dramatic processional for the visitor. The mid-19th-century appearance would have been less romantic and shady than what is seen today. The design intent was more a statement of order and prosperity. The documentary record of activities on the plantation reveals that by the mid-1830s responsibility for day-to-day management was borne by Emanuel’s son Pierre-Phanor Prud’homme, who kept two journals recording activities on the plantation. In 1861, Phanor noted that he had planted grape vines (Vitis sp.) along this “grande allee” four years earlier. Following Phanor’s death in 1865 and the subsequent division of the property in 1873, Jacque Alphonse (Alphonse I) claimed the property to the west, which he renamed Oakland (Firth and Turner, 128).

Historic American Buildings Survey LA-2-2, photographer Lester Jones, 1940, Library of Congress

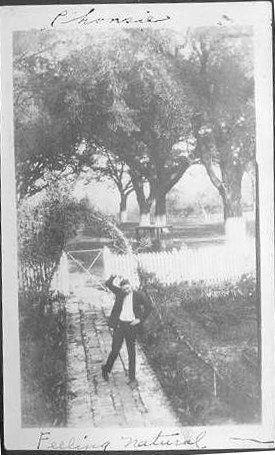

A series of historic images from the first half of the twentieth century gives additional insight into the features, vegetation, yard configuration, and general maintenance of the domestic landscape surrounding the Oakland Main House and shows lime-wash applied to the lower trunks of the live oaks and other trees in this area near the front of the property, apparently a long-established practice at Oakland (Suzanne Turner Associates, LLC., Draft Oakland Plantation CLR Phase 2 2021, 21).

Oakland Plantation Entrance Gate

Left image

Live oaks line the drive between the main entrance gate and house at

Credit: Historic American Buildings Survey HABS LA-1192, photographed by Jack E Boucher and Jon Buono, 2002, Library of Congress

Right image

A gate, rail fencing, and the live oak allee frame the entrance to Oakland Plantation.

Credit: Suzanne Turner Associates for NPS, 2017

Botanical Details

Southern live oak is a medium-sized showy long-lived evergreen tree that is native to the coastal plains of Virginia, North Carolina, and southward along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and west to southeastern Texas. It has a broad crown, rarely growing over 50 feet tall with gnarled branches that reach 40 to 100 feet wide, often seen with Spanish moss hanging from them. It is not a true evergreen but retains its leaves until the new ones begin to leaf out. Their ornamental use has long been as a large, long-lived evergreen shade tree, synonymous with tree-lined avenues. The wood is used for barrels, veneer, cabinetry, furniture, interior trim, and flooring and also has been used for pulp and firewood. It was used in ship construction, especially in the 1700s and 1800s. Many species of birds and squirrels use the tree for cover and the acorns for food. Native Americans produced an oil comparable to olive oil from the acorns.

Suzanne Turner Associates for NPS

Preservation Maintenance

Preservation is the specified treatment of the historic live oak allée. This is to be accomplished by:

-

Regular arboricultural assessments combined with pruning and fertilization, preferably on a 3-5 year cycle.

-

Replacement of trees in-kind when diseased or deceased.

-

Use of the NPS Arborist Incident Response (AIR) program if trees are damaged by storms. The AIR program consists of regional teams of tree care professionals skilled in hazard tree assessment, arboriculture, and cultural landscape preservation.

Susan Turner Associates for NPS

References

- Draft Oakland Plantation Cultural Landscape Report, Phase 2

- Cane River Creole National Historical Park Historical Resource Study

- Quercus virginiana, Missouri Botanical Garden Plant Finder

- Quercus virginiana, North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox

- Quercus virginiana, Fire Effects Information System, USDA