Last updated: October 28, 2020

Article

Captain Henry of Geauga, Part II

Library of Congress

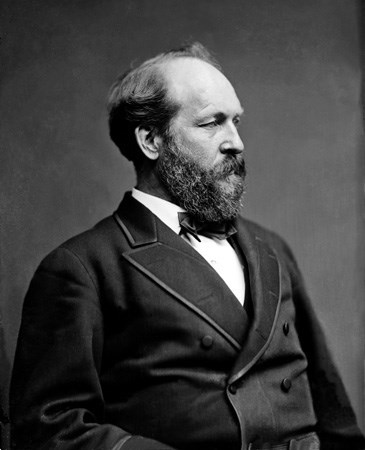

Henry was always grateful to Congressman Garfield for the railroad job. It allowed him to earn a decent living and not worry too much about farming. He began to pay attention to men having conversations about politics, particularly those in Garfield’s district. Charles wrote letters to his friend reporting on what he heard and how it related to the Congressman. Before long Charles became Garfield’s political agent. He asked questions of local folks on their views of politics in general and on important issues of the day. This was a great help to Garfield who did not have the means to keep close tab on his constituents. Henry sent newspapers to Washington for Garfield to read and decide which editors were favorable to him. Anybody in Garfield’s district that wanted a postmaster job had to have an unofficial visit with Mr. Henry before being recommended.

In 1873 Charles got a promotion to special agent of the post office department. He got a significant raise, free railroad transportation, a gun, and three dollars a day for meals. His new job allowed him to settle disputes between postmasters, investigate people for mail fraud and stealing. His duties allowed him time to stop at various points in Garfield’s district and determine which way the political winds were blowing. He reported any areas where Garfield might be losing support and what to do about it. Charles visited men who supported Garfield to make certain they were doing their utmost to keep the Congressman in office.

As special agent, Charles made about one arrest per month. He had a system for catching postal clerks who stole money out of envelopes. He would visit the post office suspected, usually wearing farm clothes so as not to arouse attention. When he had an idea who might be stealing he put several marked small bills, into two envelopes. He then addressed the envelopes for the next town on the route. Charles visited the intended post office and identified himself and alerted the postmaster to watch for the letters. He went back to the suspected post office, mailed the letters there and waited to see if they would arrive at their destination. If they did not he confronted the suspect, searched him and would find the marked money. He would make the arrest and escort the guilty party to the nearest United States marshal’s office.

Library of Congress

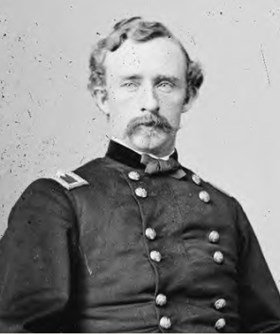

Henry’s work for Congressman Garfield did not go unappreciated. In the summer of 1874 he visited the Garfields at their Washington home. Charles got a guided tour of all the sights including Mt. Vernon, Arlington and the Smithsonian. Later in the week Garfield took Charles to the White House for a visit with President Grant. His trips to Washington became more frequent, highlighted by an army reunion and dinner with General Phil Sheridan and Colonel George Custer.

Throughout the 1870’s Charles kept a close watch on local and national politics. He counted on friends and political allies to get him inside information he could relay to Congressman Garfield. His most effective work came during Garfield’s bid for a seat in the Senate. Charles canvassed the entire state to determine how much support the candidate had. In February of 1879, Charles wrote to Garfield, “Everything looks hopeful to me and I shall be very much disappointed if you do not have a walkover.”

Soon he opened a campaign office in Columbus, handing out literature and cigars to members of the state legislature. By November he was able to report sixty-four of the ninety members were solidly behind Garfield. The actual election was unanimous, a complete victory. Charles spent only a paltry $148.60 on the campaign. When Garfield came to Columbus for his acceptance speech he grabbed his campaign manager in a bear hug and swung Charles around several times. He had done the same thing almost twenty years ago at the Hiram College graduation. Their friendship was as strong as could be.

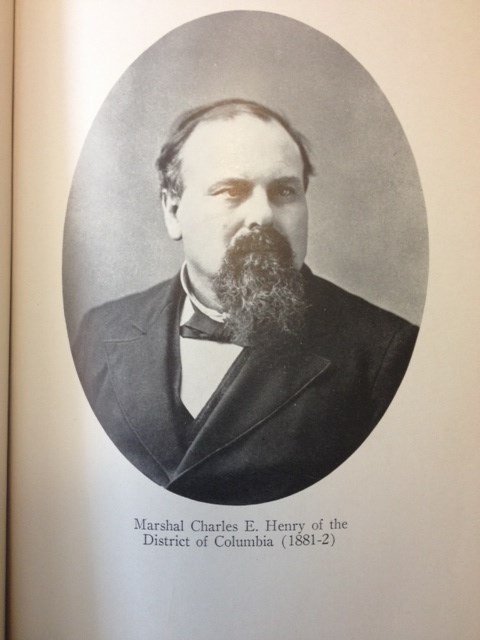

James A. Garfield never served a day in the United States Senate. In June of 1880 he unexpectedly received the Republican nomination for President. He won the general election in November to become the 20th President of the United States. Once in office he did not hesitate to appoint Captain Charles Henry as United States Marshal to the District of Columbia. Charles officially took office in May, ready to rid the streets of Washington of all criminals. He had no inkling his first major assignment would be protecting Charles Guiteau, the assassin of President Garfield. Charles did his best to put aside his hatred of Guiteau and make sure his prisoner stayed alive during his confinement. There were two attempts to kill Guiteau along with a number of unsigned letters all swearing that the prisoner would be murdered at any moment.

From the book “Captain Henry of Geauga”

Charles managed to keep Guiteau healthy throughout his trial and all the way to the execution. How he kept his composure during the ordeal is a testament to his sense of duty and personal honor. Very few men have been put to the test like Marshal Henry.

With a new President in the White House Charles knew his time in office would be brief. He survived until November of 1882 when Chester Arthur dismissed him from service. He returned home to Bainbridge to once again take up farming. For several years he produced great quantities of maple syrup and wrote article for several newspapers. Charles enjoyed being home with his family, but farm life did not agree with him. He was quite relieved when a letter from Don Pardee, now a federal judge, arrived. Pardee employed him on behalf of the court to travel to Texas and investigate a railroad labor strike. The job took several years to complete and paid Charles several thousand dollars.

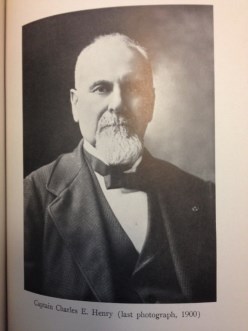

Due to his success in sorting out the railroad problems, other opportunities presented themselves. In December of 1892, attorneys Harry A. and James R. Garfield, the eldest sons of the late President, called on Charles to assist them in an embezzlement case. Their clients, a lumber company in Cleveland had lost $20,000 to one of their agents in Philadelphia. The alleged embezzler Harpin A. Botsford, pocketed company receipts and fled to Brazil where there was no extradition agreement with the United States. The Garfields believed Charles had the skills to track down the fugitive. All he had to work with was a photo of the suspect and a sample of his handwriting.

On Christmas Eve Charles boarded a steamer out of New York. His initial destination was Rio de Janeiro, a place where felons where known to frequent. After twenty-six days at sea Charles arrived in port. He immediately paid a call on the American consulate who filed the necessary paperwork for Charles to make the arrest. The Brazilian government agreed to allow Charles to take the fugitive out of Brazil should he find the culprit.

The detective work began in earnest. Charles showed the photo to a number of locals. One of the men recognized Botsford and told Charles the man in the photo was said to be on his way to Sao Paulo to buy a coffee plantation. Captain Henry located the office of a United States coffee broker who gave another positive identification of the photo. The broker knew that the suspect, now using the name H. B. Ford was on the move. Charles boarded the first train to Sao Paulo, arriving fifteen hours later.

Now hot on the trail, Charles visited the town hotels and reviewed the guest registers. At his third stop he found the name H. B. Ford, December 27, 1892. The trail was burning up. A walk to the local coffee warehouse found a worker from Scotland who had seen Mr. Ford. Charles learned through his new friend that the suspect had gone north on a narrow road to the back country. The two men boarded the only train running and arrived at a small village some twenty miles north.

From the book “Captain Henry of Geauga”

The trip turned out to be well worth the effort. Mr. Ford had been there less than a week ago. Charles learned that Botsford/Ford had hired a guide and rented mules to take him further north. They were no more than twenty miles away. Captain Henry hired the same guide to take him where he might find the fugitive. They traveled slowly through the dense, tropical forest. The road was quite rough, forcing them to dismount their mules and lead them forward. Despite encountering groups of monkeys and the occasional snake, Charles arrived at Jacutinga where his adversary was hiding. He drew both of his revolvers and moved forward.

It had been almost thirty years since Charles had worn his Union uniform but he quickly fell back to soldier mode. Ford opened his front door carrying a revolver and a machete in his boot. He looked curiously at Charles who marched up the steps, grabbed the revolver and machete and advised Ford he was under arrest. They mounted the mules and started south for the long journey that would take them back to the United States. The trip took several months, not arriving in home until April 2, 1893. For his efforts Charles received $2,000 plus extensive coverage in the newspapers.

Due to his remarkable adventure, Charles received a job offer from the American Surety Company to serve as an inspector. He continued to bring embezzlers and thieves to justice for a number of years. He did some farming, spent time with his family and kept in touch with old friends from the 42nd OVI. His eyesight began to fail and his heart weakened but Charles carried on into the 20th century. Six years later he passed away on November 3, 1906. He was seventy years old.

Captain Charles Henry was an extraordinary man: soldier, political ally, lawman, and dedicated family man. His strength of character and honesty brought him to a plateau few men occupy.

Written by Scott Longert, Retired Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, March 2014 for the Garfield Observer.