Last updated: October 28, 2020

Article

Captain Henry of Geauga, Part I

From the book “Captain Henry of Geauga,” by Frederick A. Henry

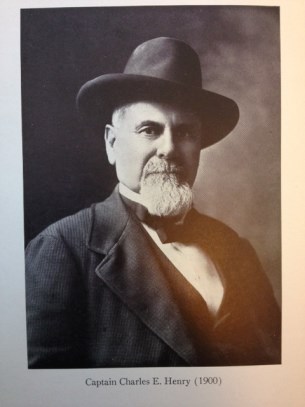

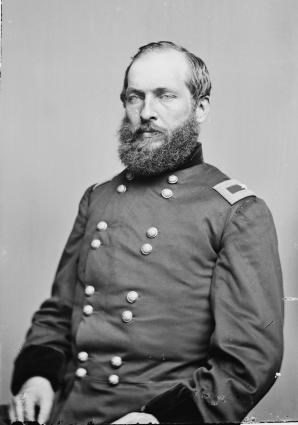

Of all the soldiers that filled the ranks of the 42nd Ohio Volunteers, perhaps none had a more adventurous life than that of Captain Charles E. Henry. This is no easy assertion to make considering the regimental commander was future President James A. Garfield. Besides our twentieth President, there would be Colonel Lionel Sheldon, a congressman and territorial Governor, and Colonel Don Pardee, a United States Circuit Court judge. These are men of great distinction, but their lives were somewhat sedate when compared to that of Captain Henry.

Charles Henry was born in Bainbridge, Ohio, November 29, 1835. He was the seventh of nine children born to John and Polly Henry. He weighed in at a shade under five pounds, so tiny that his family had great doubts of his survival. Despite a harsh northeast Ohio winter, little Charlie persevered. As a young boy he would note that travelers stopping by for a visit would often give him a few pennies to save. Charles took the coins and buried them near the Henry home. Months later he would forget where the treasure was buried.

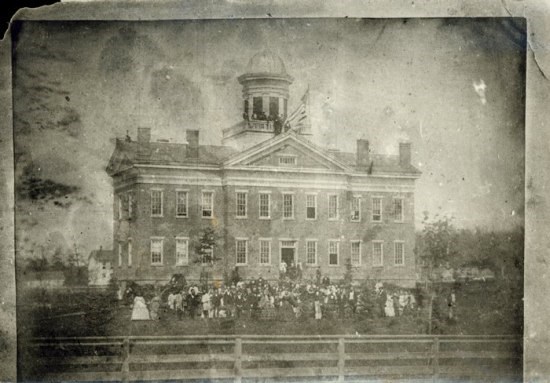

Hiram College Archives

Henry quit school at age sixteen to take on full time work. The jobs included labor in the fields, making hoops for barrels and driving teams on road construction. In just several years he had saved five hundred dollars. With the accumulated wealth, Charles decided to enroll at Hiram College. He was quite proud of the fact that he could easily pay for tuition, room and board and books. In the fall of 1857 he started classes.

Within a short time Charles became friends with James A. Garfield, currently the college principal. Despite an age difference of four years the two men became well acquainted. A year later Garfield helped his new friend find a place for room and board. For that year’s term, Charles stayed at the home of Zeb Rudolph. Charles had a fine time there, making another friend in Joe Rudolph. The two would remain pals for the remainder of their lives.

In 1859 Charles began to teach school. His first assignment was in Auburn where the school directors told him he was hired due his large size (six feet tall) and his likely ability to whip the older boys when necessary. Henry was paid twenty dollars a month for the term. The directors were probably right in hiring Charles. There were no fights during the entire school term.

The year of 1860 was a significant one for Mr. Henry. Back at Hiram, he scheduled the most challenging classes he could find, including algebra, chemistry and German. He joined the Delphic Literary Society, sometimes donating his own books to the society library. Charles recalled a particular meeting where he made eye contact with one of the members of the Olive Branch, the only female society on campus. Her name was Sophia Williams; quiet a beauty in her day. Charles left the gathering early but was stopped in the street by one of his friends. Apparently Ms. Williams was miffed that Charles left and asked his friend to bring him back. The two sat together and talked, the beginning of a courtship that would later result in marriage.

By the spring of 1861, Henry was near graduation. He spent a lot of time doing military drills on the common. The attack on Fort Sumter had already taken place, prompting many of the Hiram boys to ready themselves for war. Some would drop out of school and enlist. Charles stayed the course and graduated on June 6, 1861. His commencement oration received high praise from Principal Garfield who lifted Charles off the ground and swung him around in admiration. They were now the best of friends.

For the next two months Charles Henry mulled over his future. He had an offer to teach the winter term at the Solon school district. Dr. David Shipherd, an old family friend wanted Charles to study medicine and take over his long established practice. While debating the offers, two visitors came to see the recent graduate. They were Lieutenant Colonel Garfield and Frederick Williams, a classmate of Charles. They were on their way to Hiram to recruit soldiers for the newly formed 42nd Ohio volunteer Infantry. They would not leave until Charles accompanied them. The meeting took place that evening and the first recruit to sign up was Private Henry. Company “A” soon held elections for officers. The vote for Lieutenant was hotly contested with Charles losing by a single vote. The next day he was appointed first sergeant.

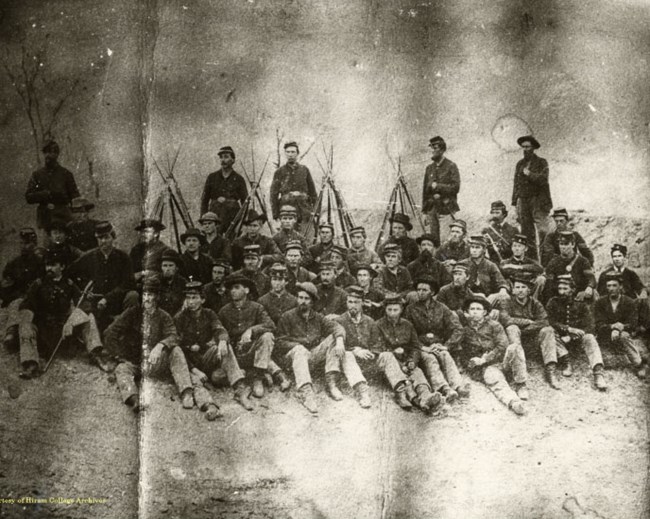

Hiram College Archives

The 42nd OVI saw action in Kentucky, Tennessee and Mississippi. They took part in General Grant’s Vicksburg campaign which ended with the siege of Vicksburg. Company “A” was at the thick of it in most of the battles. A significant number of Hiram boys were killed or wounded during their three years of service. On May 22, 1863 the 42nd received orders to storm the Rebel forts protecting Vicksburg. Lieutenant Henry (a recent promotion) led the advance of Company A through a narrow valley and up the steep hills. The Rebels blasted away at the Union soldiers. Lieutenant Henry took a bullet in his left foot which shattered a small bone. He managed to slide down the slope and painfully limped to the field hospital. He received treatment and a twenty day leave to recuperate.

The twenty days leave turned into several months before Lieutenant Henry was able to report for duty. Upon his return he received orders to report to Baton Rouge, Louisiana where he would be appointed Assistant Provost Marshall. His new boss would be Colonel Don Pardee, temporarily detached from the 42nd OVI. Though not well acquainted, the two men became fast friends. The Provost Marshall’s office had a wide variety of duties to perform including keeping the peace among the residents, trying military cases and making sure the occupying army did not get too out of control. Charles made a thorough study of the law, soon acting as representation for soldiers on trial. He was not a practicing attorney but learned how to prepare an adequate defense.

Henry became adept at identifying ladies of the community who were actively involved in smuggling. After signing an oath of loyalty to the Union these women went to the area druggists and bought illegal medical supplies for sick Confederates hiding out in the country. The ladies sewed small bags inside their dresses and would load up for a visit outside town. Charles developed a knack for eyeing the ladies and recognizing strange bulges in their clothes. Most of the women he stopped were carrying contraband and wound up paying heavy fines.

Library of Congress

Charles left for home where he was mustered out of the army and brevetted to the rank of Captain. A month later he married the pretty girl from the Olive Branch Society, Sophia Williams. After a honeymoon at Niagara Falls, Charles returned to Baton Rouge where he acted as an independent advocate for soldiers and civilians. In just a few months he earned $3,000, enough to buy a one hundred acre farm in Bainbridge. Business was booming for him, enough to bring Sophia to Baton Rouge. She was not a fan of the sweltering temperature, but the Henrys stayed for a while to build up their savings.

Eventually they returned to Bainbridge where Charles put away the law books and took up farming. He threw himself into the work but the results were not promising. For some reason he never took to farming. He did not make money no matter how hard he tried to succeed. In 1867, he supplemented his income by becoming the local postmaster. This worked for two years until the job was eliminated. He then wrote a letter to old friend (now Congressman) James A. Garfield, asking for a postal clerk position with the railroad. In short order Charles got a job with the rail line from Cleveland to Youngstown to Sharon, Pennsylvania. He manned the rail car five days a week, sorting letters and newspapers and filling mailbags.

Several months later Charles proved his value to the railroad. A group of tough guys boarded his train, carrying roosters on their way to a cock fight. On the return trip the men were obviously drunk and harassing the passengers. Though not part of his duties Charles confronted the men, grabbed several and threw them off the train. This action would benefit him in later years.

(Check back soon for Part II of this article!)

Written by Scott Longert, Retired Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, March 2014 for the Garfield Observer.