Last updated: March 10, 2023

Article

Cache

Project Gutenberg

Rivers change course over time. The place where Meriwether Lewis and William Clark saw the confluence of the Missouri, Marias, and Teton Rivers is not the same exact location where you can now see the confluence.

Even the expedition—in their short trip in the region—saw this confluence at two different points in time: first in June 1805, and on the way back, Lewis’s party saw it in July 1806.

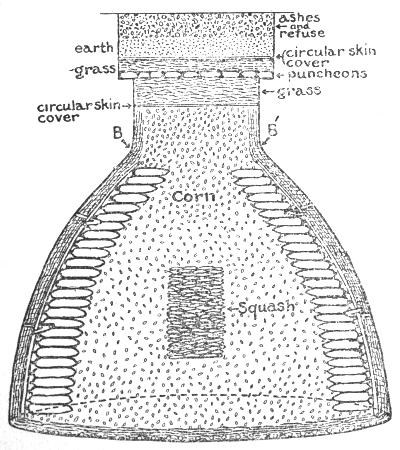

When they passed the confluence the first time, they put some of their things in a cache to pick up on the return journey. They did this because knew they could not carry everything over the mountains. A cache is an underground earthen storage tank. It was a familiar tool for members of the expedition who had been traders along the Ohio, Mississippi, and Missouri Rivers. One of those men, Pierre Cruzatte, took the lead in creating a cache for their excess baggage.

Lewis described the careful process, which included cutting a twenty-inch-wide hole in sod and then carefully digging out a six- to seven-foot-deep hole. Cruzatte used dried sticks and animal skins to keep the merchandise they deposited from rotting in the soil. They stored ammunition, axes, hammers, other tools, flour, pork, salt, chisels, tin cups, animal skins, horns, beaver traps, and more in the cache.

So, did it work?

Kind of.

When the party returned the following summer, Cruzatte examined the cache he had made. Two bearskins were completely ruined. But the “gunpowder corn flour poark and salt” were all in pretty good shape. Three animal traps that Drouillard had stored in the hole were missing entirely.

Other people visited this area regularly—Blackfeet, Shoshone, and others. Would they have noticed the small disturbance in the groundcover in the year that it was there? Did they wonder what might be beneath it?

About this article: This article is part of a series called “Pivotal Places: Stories from the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.”