Last updated: March 8, 2025

Article

Buck Island’s Corals Get Relief from a Deadly Disease

Through trial and error, outreach, and a small army of volunteer divers, scientists slow the progress of one of the Caribbean’s most lethal coral diseases—for now.

NPS / Kristen Ewen

Buck Island Reef National Monument’s beautiful blue waters and sandy shores would put anyone in vacation mode. As you bathe in the warm Caribbean sun, the feeling of "nothing could be wrong in this tropical paradise" sets in.

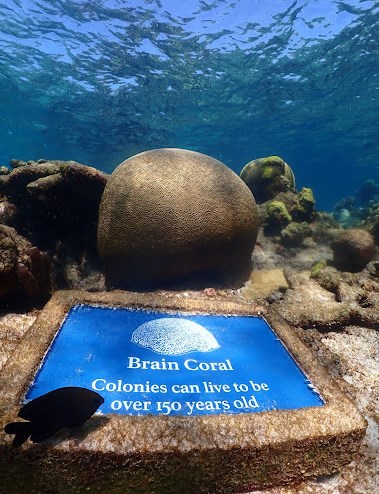

But this feeling fades for those who venture below the surface. On July 25, 2021, biologists raced to Buck Island to respond to a report that one of the deadliest known coral diseases had attacked corals in the park. As park divers entered the water, it was clear that this was no false alarm. Brain corals had developed white dots overnight, a sign that disaster had struck: the corals were under attack from stony coral tissue loss disease. With luck, dedication, and community spirit, the park brought the disease under control, but the fight isn’t over.

Image credit: NPS

How It All Began

President John F. Kennedy established Buck Island Reef National Monument in 1961. He proclaimed that this marine protected area off the northern coast of St. Croix protects “one of the finest marine gardens in the Caribbean Sea.” But within a decade of its establishment, the park suffered several major coral disease outbreaks. The causes of these outbreaks still remain largely unknown.

Corals are marine animals, and just like humans, they can catch and spread diseases. In 1977, marine researchers found a new coral disease referred to as white-band disease on reefs in St. Croix. Since then, researchers have reported over 30 coral diseases (76 percent of all coral diseases) in Florida and the Caribbean. Scientists now consider disease one of the greatest threats to corals and reefs in that region.

"There is a stark difference between what the reef looked like when I arrived in 2020 to its current state."

In the 1980s, white band disease reduced coral cover over 90 percent in two prominent reef-building corals (elkhorn and staghorn) at Buck Island. Elkhorn and staghorn populations rarely recovered after the white band disease outbreak. These Buck Island “poster child” corals now reside in small, isolated communities throughout the park. When President Clinton expanded the park boundary in 2001, the monument grew from 704 to 19,015 acres of marine habitat, a little over the size of 14 football fields. National Park Service staff struggled to manage the continued threat of white band and other seasonal, annual coral disease outbreaks related to the changes in ocean temperatures in the expanded park. “There is a stark difference between what the reef looked like when I arrived in 2020 to its current state,” said Matthew Warham, Coral Reef Initiative coordinator for the U.S. Virgin Islands Department of Planning and Natural Resources. “To see coral reef health and diversity decline on a monthly basis is eye opening on how quickly our resources can be adversely affected and potentially disappear.”

Image © Sonora Meiling

Since the early 1990s, coral disease outbreaks have been more frequent and intense. This is because the corals are stressed. The factors contributing to that stress—such as warming water temperatures—increase yearly. Corals under stress, just like humans, can’t fight off diseases as well as when they are healthy. The diseases are often difficult to manage. How do diseases spread? What causes them? How do we treat them? The answers to these questions are different for different diseases and sometimes unknown.

Through collaborative research on pathogens, treatment methods, and disease transmission, Buck Island and other marine parks have made major strides in managing coral diseases. The park’s collaborators include the U.S Virgin Islands Department of Planning and Natural Resources, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, The Nature Conservancy, Mote Marine Lab, and the University of the Virgin Islands. In 2021, Mote Marine Lab discovered a new treatment for recurring black band disease, reducing its impact on the park’s reefs. But the Caribbean may now be facing its greatest threat—stony coral tissue loss disease.

A Lethal Aggressor and a Partial Cure

Stony coral tissue loss disease spreads much faster, affects more coral species, and is more lethal than any other known coral disease. The disease transmits through water, creating lesions of tissue loss and exposed skeleton. A coral can develop multiple lesions that rapidly spread across the coral surface at a rate of more than one inch per day. Once affected, corals die over the course of weeks to months. This reduces important marine organism and fish habitat and weakens the health and resiliency of the reef ecosystem. Scientists across Florida and the Caribbean are working to uncover the cause of this disease and continue to document its devastating impacts. On some reefs, the disease has already reduced coral cover by more than 40 percent.

Coral reef scientists first reported stony coral tissue loss disease off the coast of Miami in 2014. The first appearance of the disease in the U.S. Virgin Islands was in January 2019 on a reef off the south shore of St. Thomas called Flat Cay. It has now spread across most reef systems in St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix. It made its first appearance in Virgin Islands National Park, Buck Island, and Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve in early 2021.

A coral can develop multiple lesions that rapidly spread across the coral surface at a rate of more than one inch per day.

Current treatments for other coral diseases include amputating the affected area and cutting a trench into the coral between diseased and healthy tissue, referred to as a “fire break.” But these treatments are not effective enough against stony coral tissue loss disease. Fortunately, through trial and error, researchers in Florida discovered that applying antibiotics on the disease margin of lesions using syringes or caulk guns is effective. Even though amoxicillin reduces lesion progression and is the most prominent method of treatment, it isn’t foolproof. It has a success rate of around 75 percent. The National Park Service and other state, territorial, and federal agencies also remove corals from the water and store them at land nursery facilities to protect them from local extinction until the outbreak has run its course. “Even though a majority of corals are in a pretty desperate state, we are seeing corals that are resistant to the disease out on the reefs,” Warham said. “This gives our team hope that we can collect these strong, resilient individuals to grow more of them to restore our reefs.”

How do we apply antibiotics to a coral reef? It helps to have friends. A working group of national parks, other agencies, local organizations, and universities came together in 2019 to maximize control of coral diseases in the Virgin Islands (U.S. and non-U.S.). They called themselves the Virgin Islands Coral Disease Advisory Committee. The committee dedicated itself to closing knowledge gaps and coordinating efforts to combat stony coral tissue loss disease. They formed small strike teams of local volunteer divers. Since 2019, diver strike teams have administered over 11,653 amoxicillin treatments to corals in the waters surrounding all three U.S. Virgin Islands, including sites within the parks. The network of scientists and the lessons learned from these collaborations allowed the park to use the most effective, up-to-date methods and respond to the disease successfully.

Image credit: NPS

A Trail Under Attack

On the east side of Buck Island Reef National Monument is a shallow water lagoon protected by a barrier reef. It is the perfect place to snorkel and dive in calm waters. As you enter the most popular site, the Underwater Trail, interpretive signs guide you through shallow grottos filled with gardens of brain coral. In June 2021, the trail became a hotspot for stony coral tissue loss disease because of brain corals’ susceptibility to the disease. It spread rapidly.

The prominence and severity of the disease and the popularity of the Underwater Trail led the park to quickly mobilize its own strike team, bringing together park staff and volunteer divers. The strike team treats corals frequently, over a wide area. It tracks disease progression and refines treatment methods to improve efficiency and treat even more corals. Since the initial outbreak, the park has treated four focal sites within the lagoon at Buck Island and has started to treat other priority sites within the park’s boundaries. The team’s treatments have stopped lesion progression 85 percent of the time. Park staff and volunteer divers have successfully treated over 800 corals and continue to treat them weekly.

"Even though these corals are not charismatic animals, you still become attached to them. They turn into the ‘residents’ of the reef. It is really difficult to watch these residents die in a matter of months if left untreated."

“We end up visiting our priority sites on a bi-weekly basis,” said Biological Science Technician Alana Nunn. Nunn is a strike team leader with the National Park Service. “Even though these corals are not charismatic animals, you still become attached to them,” she said. “They turn into the ‘residents’ of the reef. It is really difficult to watch these residents die in a matter of months if left untreated.“

Image credit: NPS / Kristen Ewen

The Park Strikes Back

Christiansted National Historic Site, the park that manages Buck Island Reef, has a small staff to take care of its natural resources. To expand treatments to the entire park, we needed to think outside park boundaries. The park recruited citizen scientists from local territorial government agencies, nonprofit organizations, university students, and the public. These workers reported disease sightings within park boundaries, recording them in a database, and took pictures of tagged corals. This helped the park get more frequent data on lesion progression. The park also increased disease awareness and promoted actions to reduce spread through public outreach workshops and by training park concessionaires in decontamination protocols.

“Educating the public on what to look for and the differences between disease and other factors causing coral decline really opens their eyes to what is happening,” Warham said. “If you do not know what a healthy reef looks like, your baseline will continue to shift. And everything will seem fine when it is actually declining at an excessive rate.”

"We want to make sure they are aware of what they could potentially lose, so that they have an opportunity to help save it."

Stony coral tissue loss disease now affects most reefs in the territorial boundaries of the U.S. Virgin Islands. To successfully combat this disease, we need many hands. Local, state, and federal agencies continue to encourage communities to assist in treating corals. In September 2021, the National Park Service hosted their first treatment workshops to train new snorkelers—including concessionaires—to identify disease and administer treatments.

“It is so valuable to educate the public on the impacts of this disease, because it is their resources and reefs that we are trying to preserve and restore,” said Nunn. “We want to make sure they are aware of what they could potentially lose, so that they have an opportunity to help save it.”

Through the work of volunteers and research collaborators, the agency hopes to help smaller parks successfully respond to this deadly disease and give the nation’s coral reefs a much-needed reprieve.

About the author

Kristen Ewen is a National Park Service biologist and park dive officer for Christiansted National Historic Site in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands. A part of her job that she really enjoys is having volunteers, especially young student groups, join NPS staff on resource management projects. She believes the future of our oceans depends on connecting the next generation with the knowledge and experiences that will ignite a lifelong passion for preserving this fragile ecosystem.