Last updated: January 19, 2024

Article

Brownfields Funding in Historic Preservation

Article from the proceedings from Are We There Yet? Preserving Roadside Architecture and Attractions, April 10-12, 2018, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Watch a non-audio described version of the presentation on YouTube.

By: K. Michelle Barnett, City of Tulsa Brownfields Program

Abstract

In 1927, Tulsan Cyrus Avery established Route 66, the Mother Road, running from Chicago to Los Angeles, including 30 miles in the heart of Tulsa. The cars and trucks that traveled Route 66 catalyzed businesses along the corridor. Service stations, gas stations, plating shops, painting operations, motels, and salvage yards blanketed the landscape. But today, the very businesses that once made the corridor hum with energy need modern financial and cleanup tools for redevelopment.

Whether a property is perceived to be contaminated or actually is, owners can expect that there will be costs to address environmental issues. Typical contamination associated with historic properties includes asbestos in insulation, vinyl tile, mastic, ceiling tiles and more; lead-based paint on surfaces; petroleum products at former gas stations and service stations; and metals from plating and manufacturing.

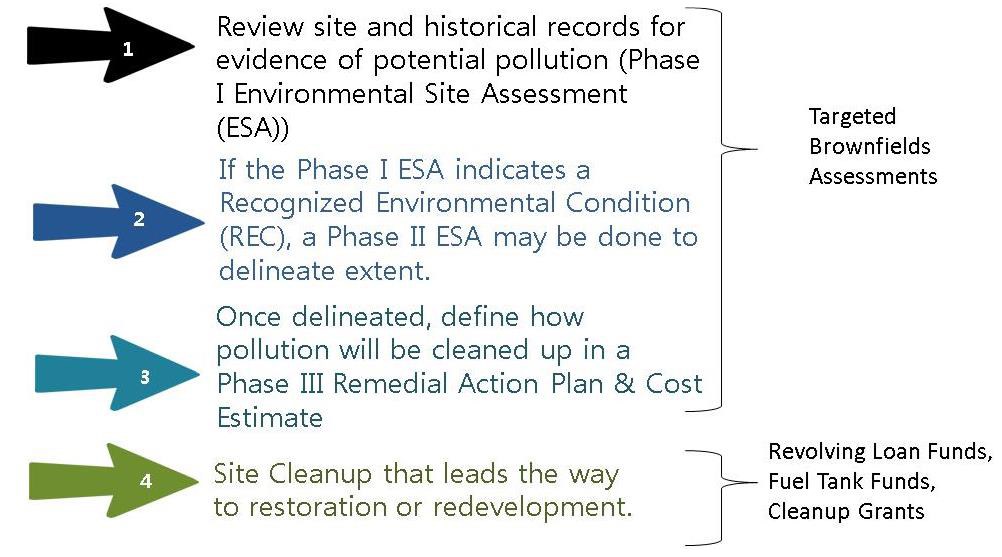

Depending on your location, funds may be available at the local, state, and federal levels to help assess, characterize, and cleanup both interior and exterior contamination. At the local level, many communities manage Revolving Loan Funds (RLFs) which provide low interest loans and grants for site cleanup. Communities may also have funds available to assess and characterize contamination prior to cleanup. At the state level, similar programs area available including the RLF for cleanup as well as Targeted Brownfields Assessment (TBA) funding for site environmental assessment and characterization. At the federal level, additional TBA funding is available to help buyers determine what contamination may exist at a property or to characterize the extent of contamination and to conduct cleanup planning and cost estimating. Properties held by municipalities or tribal governments may also apply for cleanup grants from the USEPA to help restore properties to use.

Brownfields

The “Small Business Liability Relief and Brownfields Revitalization Act” signed into law January 11, 2012, defined a brownfield as real property, the expansion, redevelopment, or reuse of which may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant. Brownfields are often found at industrial facilities but, can be present in much smaller, everyday buildings as well. A basic knowledge of brownfield programs can be helpful to preservationists as rehabilitation projects commonly encounter environmental issues. In terms of roadside architecture, brownfields are often found in the form of fueling and service stations with leaks of gasoline or other petroleum products in soil, groundwater, or vapor. Brownfields are also present at many of the commercial services that kept autos moving across the landscape: chrome plating operations, paint and body shops, and similar facilities.

The presence of brownfields in a community can bring renewal efforts to a standstill. Brownfields can be costly to clean up and revitalize. It is understandable that otherwise eager investors can be scared off from potential brownfield sites. It is worth noting, however, that brownfields development projects leverage $16.11 per federal dollar invested nationwide and have created more than 97,000 jobs (EPA, 2017a). An economic impact study by the State of Oklahoma also showed that for every $1 of federal investment in that state’s brownfields, $17.98 was returned in the form of federal income taxes. Furthermore, brownfields cleanup provide economic engines for communities. Economic output on properties surrounding restored brownfields increased more than $2 billion since Oklahoma’s brownfield program started 20 years ago (Oklahoma Department of Commerce, 2008).

In one example, the town of Sayre, Oklahoma used state assessment and revolving loan funds to clean up 19 former fueling stations along Route 66, which is also that city’s Main Street. This investment led to redevelopment throughout the downtown corridor (EPA, 2009). Once the initial financial hurdles were overcome, the benefits of brownfield reuse released additional resources.

Preservation projects have their share of fiscal challenges as well. Developing plans in accordance with NPS guidance and conducting restoration is typically more expensive than starting anew in another location. For businesses, the time to conduct documentation and plans development is also costly, with each day one that they are not creating revenue. And homemade roadside attractions, though unique, are often tied to the abilities of their creators for maintenance. Think of the kudzu-wrapped fate of Margaret’s Grocery outside Vicksburg, Mississippi after the death of its builder in 2011. Thankfully, combining brownfields with preservation makes these projects more feasible, rather than less.

There are a number of tools available for both historic properties and brownfields that can be utilized to create a capital stack including historic tax credits, brownfields tax credits, and direct funding for assessment or cleanup. In Flagstaff, Arizona, former fueling stations were being repurposed for commercial development, but growth of the Route 66 commercial district was hampered by concerns regarding the potential for leaking USTs along with soil and groundwater questions. By leveraging an assessment grant from EPA, the city created a brownfields inventory supported by site-specific studies documenting the condition of each property. In quantifying the perceived risk, the city removed barriers to reuse and preservation of historic buildings. By combining both brownfield and historic preservation tools, developers, communities, and non-profits can come together to restore architectural features and create public assets. This paper explores several financial tools for preservation at brownfield sites.

Environmental Due Diligence and Assessment Funding

Buying a property involves some level of risk. When you find a new home, a building inspection is typically performed prior to purchase. The home inspection provides a prospective owner with information about the home’s roof, structure, foundation, plumbing, mechanical systems, and so on such that the buyer can make an informed decision. Too many red flags and the buyer may choose to walk away, or they may use the inspection as a tool for negotiation. Either way, due diligence removes some of the worry associated with making a significant investment.

Similarly, environmental due diligence is conducted prior to purchase to assess the environmental condition of a property based upon its history, past operations, documented environmental compliance, and site review by a Qualified Environmental Professional. Like a home inspection, if environmental due diligence finds too many issues, a purchaser may decline or negotiate. The guidance for environmental due diligence is established in ASTM E1527-13: Standard Practice for Environmental Site Assessment (ESA): Phase I Environmental Site Assessment Process. This practice allows the user to qualify for the limitations of liability provided under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) as an innocent landowner, a contiguous property owner, or a bona fide prospective purchaser. In layman’s terms, a Phase I ESA documents that you didn’t cause the problem and can’t be held legally responsible for cleaning it up.

Performing environmental due diligence can come with its own set of costs, however. A Qualified Environmental Professional will charge $3,000-$4,000 for a Phase I ESA. And if an historical structure is being considered, the cost of an asbestos survey should be added to that figure. When environmental issues are found by the Phase I ESA, a Phase II investigation may be required to define how the extent of the problem. The cost of these services can range from the tens of thousands to over $100,000. However, these costs are nothing compared to purchasing a property and then finding it to be unusable or unsafe.

Understanding the barrier that environmental due diligence can pose, the EPA provides Targeted Brownfields Assessments (TBA) through its contractors as well as through state and tribal environmental programs. TBA programs at the federal, state, and tribal levels can be located by first finding the local EPA geographic region and then the appropriate state/tribal agency.

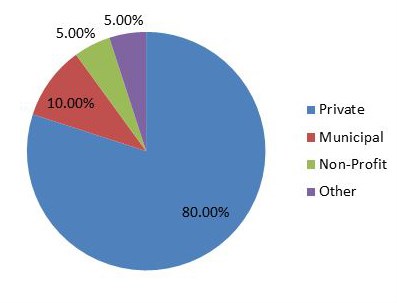

The EPA TBA program is available to public entities (e.g., municipalities, regional planning commissions) or non-profits who partner with a public entity. This encompasses approximately 15%-20% of all brownfields sites as shown by the pir chart below. Non-profit entities may coordinate their community, tribe, or regional environmental coordinator to apply for TBA funds.

To be eligible, the applicant should own the site or have the ability to own the site. If the applicant does not currently own the site, they should be able to show that the current owner has shown no interest in the property, has not paid taxes on the property, or does not have the resources to conduct the required site assessment work. In addition, the applicant should have a plan to redevelop or reuse the impacted property. If the applicant has caused the site to be impacted, they are not eligible for assistance. The TBA program is not intended for use by private parties.

EPA has established a maximum of $200,000 per site for TBA activities, though demand for the program requires that its projects average $50,000-$100,000 per site (EPA, 2018). As an example, in Allentown, Pennsylvania, EPA TBA funds were used to assess soil and groundwater impacts from historic steel operations at the Lehigh Structural Steel Company. The TBA activities were conducted by an agency contractor and included Phase I and Phase II ESAs to determine the extent of metals contamination at the site. A Phase III ESA and Cost Estimate were performed to develop alternative cleanup options for the site including technical specifications for capping the site and landscaping plans as well as a soil management plan to address how contaminated soil would be managed, if encountered during construction activities. Restoration of the riverside property made this previously unusable site into an economic contribution to the region. The property is currently valued at over $300 million and will provide an additional $5 million in real estate taxes to local government.

The Oklahoma Ironworks Company was a metalworking facility and foundry located adjacent to Tulsa, Oklahoma’s central business district on 23 acres. During its heyday, the site was the largest steel producer west of the Mississippi River. After closing in the 1960s its condition deteriorated and in the 2000s, it was recognized that redevelopment would first require action on the part of the city for cleanup. With a clear plan for redevelopment, the City pursued federal TBA funds to have Phase I, II ESAs and a Phase II Alternative Analysis and Cost Estimate performed between 2009 and 2011. The city approached the state Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) regarding risk-based remediation of soil and groundwater. However, the DEQ identified additional data needs that would need to be addressed before they would approve a risk-based site cleanup and closure. The City applied to the DEQ for state TBA funds to address the data gap and another TBA Phase II ESA was conducted by the DEQ. Using the combined data from federal and state TBA ESAs, the city successfully applied to the DEQ for risk-based closure and entered into a Memorandum of Agreement with the DEQ. Cleanup of the site is ongoing and will be completed in fall 2018. The site will be redeveloped as the national headquarters and Olympic Training Center for USA BMX with a value of over $15 million.

Revolving Loan Funds

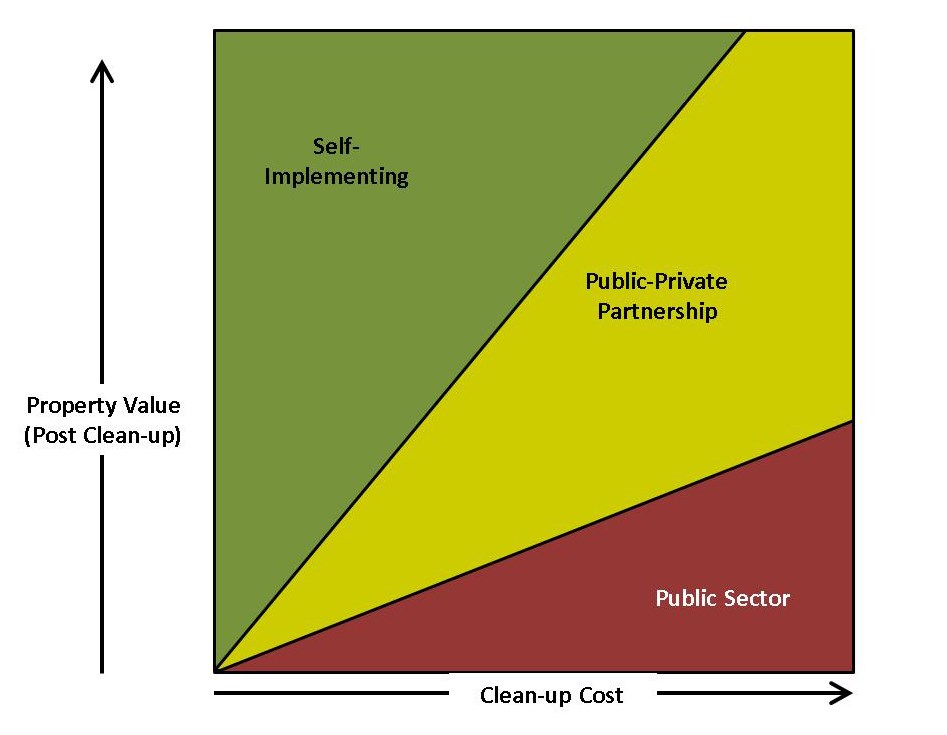

It is recognized that many environmental cleanup projects happen without public assistance of any kind. If the property value is high and the cleanup costs are low, environmental activities are often conducted by the owners. These are called “self-implementing” cleanup activities. However, when property values are moderate and cleanup costs are high, some type of public-private partnership may be required to make the project feasible. One of these tools for public-private partnership financial assistance is a Brownfield Revolving Loan Fund, or RLF.

The City of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma initiated its Brownfield RLF with a seed money coalition grant from the EPA. The grant funds were then used to make low-interest loans to private entities for environmental cleanup within the coalition’s geographic limits. Brownfield RLF funds can be used to address hazardous materials, including asbestos and lead-based paint, as well as petroleum, mold, controlled substances, and animal waste at contaminated sites. Through the RLF, the city has provided loans for individual environmental clean-up projects to local businesses and developers. For example, a loan was made on the “Steelyard” redevelopment adjacent to a former oilfield near the downtown central business district. The five-acre site contained numerous underground storage tanks, oil wells, and metals contamination. The city’s brownfield RLF provided a loan of $1.3 million to the project for environmental remediation with balance of cleanup funded by the developer. The site opened in 2017 with mixed-use commercial and residential development of retail on the first floor and loft housing above (EPA, 2017c).

In Tulsa, Oklahoma a downtown high-rise building where asbestos abatement costs were estimated at over $50,000 per floor was the recipient of a local brownfield RLF loan. The building was also a contributing element to a National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) district. The National Park Service (NPS) oversaw the building’s restoration which allowed the owner to make use of state and federal historic tax credits. At the end of the cleanup phase, the loan was repaid to the city and long-term project financing obtained. In this way, the RLF functioned as a bridge loan. The interest and principal repayment accrued to a program income account, which will be recycled back into the community for additional environmental activities.

Unlike the TBA program, RLF loans are available to private entities and non-profit organizations that own brownfields. The RLF applicant must be able to document that they did not cause the property contamination, typically through a Phase I ESA. The applicant must also have the capacity to repay the loan and a plan for redevelopment or reuse. Project funding is determined based on environmental impact, public health and safety, economic development, community benefit, and neighborhood revitalization.

In Wilson, North Carolina, the Vollis Simpson Whirligig Park became home to 31 kinetic sculptures created from spare parts by a local farmer for whom the park is named. Mr. Simpson had donated the sculptures to the city after deciding that he was no longer able to maintain them. The city has since worked with the NPS to develop a conservation plan for the sculptures and leveraged over $1 million in grants from the National Endowment for the Arts towards whirligig conservation and the parks creation. The State of North Carolina even declared the Vollis Simpson whirligigs to be the official state folk art. Spurred on by their success in creating the park, the city pursued and was awarded $160,000 to create a farmer’s market shelter next to the park as well as a $10 million TIGER Grant from the Department of Transportation to improve access (NEA, 2018).

The resulting infrastructure investments have attracted over $30 million in private investment to the area surrounding the park. A brownfields assessment grant was obtained by the EPA for $200,000 to support Phase I and II ESAs on properties in the city of Wilson where redevelopment is occurring. The EPA followed up on the assessment grant with $1 million in seed money to establish brownfield RLF supporting redevelopment efforts (EPA, 2014).

Brownfield RLFs can be used to remove, mitigate, or prevent further release of hazardous materials or petroleum. This may include securing a site with fencing, placing warning signs, or other site control measures. Because storm water can be a contaminant transport mechanism, installing drainage control features may be addressed as well as stabilizing berms, dikes, impoundments, or lagoons. Capping contaminated soils, for example by paving, may be conducted using the RLF. The RLF is also used for cleanup, often excavation or removal of affected soil or groundwater or abatement of asbestos and lead-based paint. RLF funds are applicable to disposal or treatment of contaminated materials after removal as well. Other aspects of cleanup, such as public participation and worker health and safety are also components that may be funded through the RLF.

This financial tool is available at the state level as well as through many municipalities and regional planning commissions. The EPA provides a searchable database of all grantees to help identify RLF providers in your area. RLF awards are not limited in value but are based upon availability of funding and ability of the applicant to repay. Terms of RLF awards are typically negotiable both in duration and rate, although a match of 20% is required on the part of the applicant. In the example above, the applicant provided in-kind match in the form of limited demolition to expose the asbestos for abatement. Documentation of labor payments and contractor waste disposal costs were used to quantify the in-kind match. The building is being returned to use as a hotel within the central business district.

Petroleum Storage Tank Funds

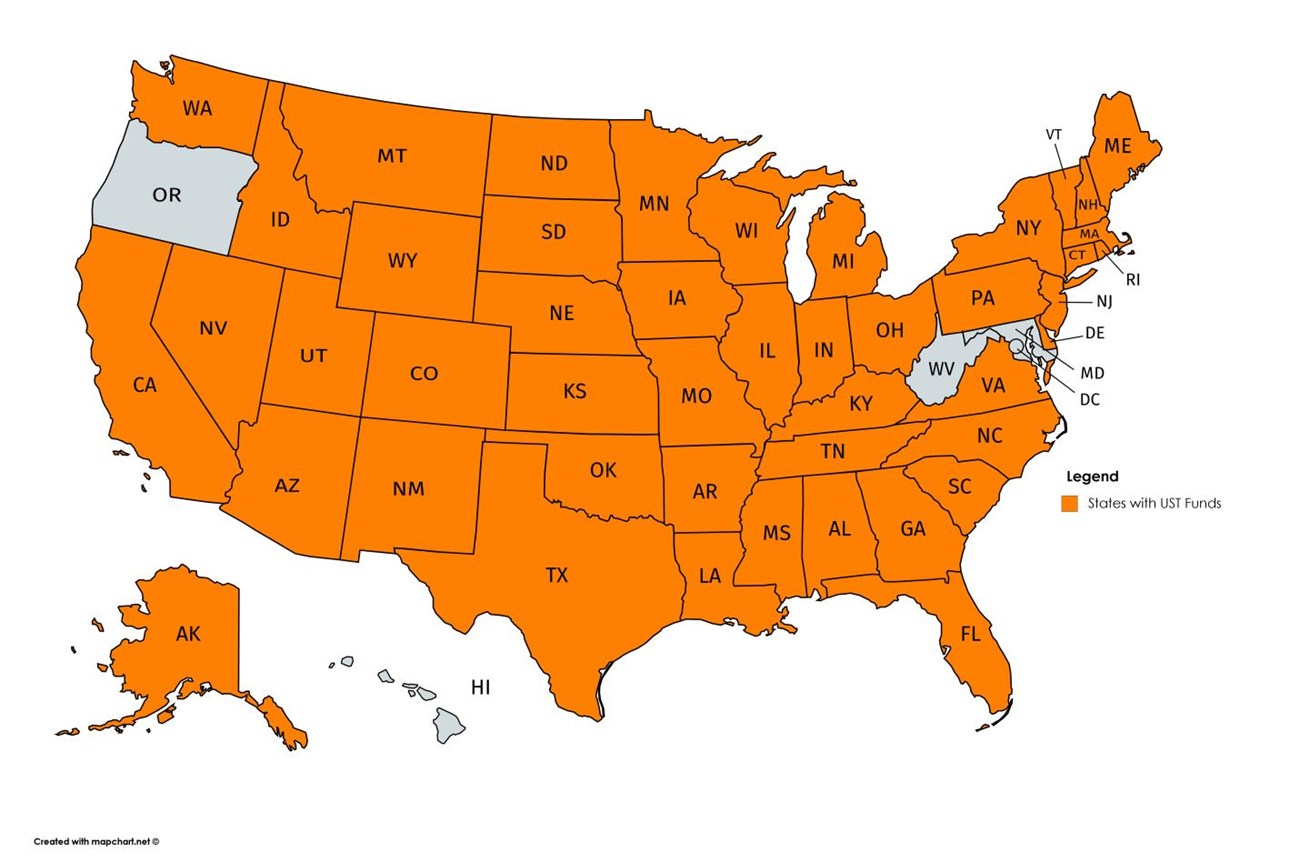

In 1986, the federal Leaking Underground Storage Tank (LUST) Trust Fund was created to address contamination from USTs. Each year, the EPA UST program distributes approximately $90 million from the LUSTS Trust Fund to states and tribes to prevent, detect, and clean up releases from USTs. In addition, states annually raise and spend approximately $1 billion for tank cleanup (EPA, 2017b). Nationwide, all but a few states currently manage funds to address abandoned fuel tank contamination.

Because each state has its own criteria for use of petroleum storage tank funds, the following are overall guidelines. Owner or operators of fuel storage tanks may be eligible for petroleum storage tank funds. This does not mean that the owner ever used the tanks. In fact, many tank cleanups are performed for businesses that are reusing or repurposing a former fuel station. If the owner has operated the tanks, they must have done so in compliance with current regulations for fuel tanks. It is necessary for a non-operating owner to be able to document that they did not cause the contamination, typically by having conducted a Phase I and Phase II ESA prior to purchase. Entities that are ineligible for storage tank funds are refiners, transporters, and owners or operators who knowingly have allowed releases to occur or who have not cooperated with regulators on corrective actions.

Because many former fueling stations operated prior to rules requiring their registration, there may be no records of fuel tanks having been located on a property. In this case, having performed a Phase I ESA can be especially important. Historic research of property history, from aerial photos, chains of title, or city directories, can also be helpful in documenting that a facility was, in fact, a former fueling station long after buildings have been removed. This documentation will be required by the fund agency to qualify for coverage if the facility operations pre-dated state tank registration programs.

Activities which are normally covered by petroleum storage tank funds include:

- Assessing the extent of contamination in soil, groundwater, or vapor;

- Preparing corrective action plans;Disposing of and treating impacted soil, groundwater, or surface water;

- Monitoring soil, groundwater, surface water, or soil vapor;Maintaining clean-up equipment if a long-term treatment system is installed; and

- Decommissioning a site once cleanup has been completed.

- One important item that is not covered by most state petroleum clean-up funds is tank removal. This is because the presence of tanks does not mean that an environmental issue exists. Rather, environmental impacts are present if a release from the tank has occurred and if the release extends beyond the tank backfill.

One important item that is not covered by most state petroleum clean-up funds is tank removal. This is because the presence of tanks does not mean that an environmental issue exists. Rather, environmental impacts are present if a release from the tank has occurred and if the release extends beyond the tank backfill.

According to the EPA, over 538,000 UST releases are known to have occurred. Cleanup work has been diligently progressing and EPA estimates that over 469,000 contaminated sites have been cleaned up. While this shows significant progress, there are still thousands of leaking storage tank sites nationwide, though. Because there are so many old fueling stations across the country and a significant demand for petroleum clean-up funds, there is competition for storage tank funds and not all projects are accepted into state storage tank programs. These sites are still eligible for the brownfield RLF funding described previously.

Duncan Oil was a postwar oil business that consisted of two buildings and 32 storage tanks on 1.38 acres in Franklin, NC. Over a half-century of operation, leaks of diesel, kerosene, and gasoline from both above and underground storage tanks had impacted soil at the site. The oil company was constructed over the Cherokee town of Nikwasi and adjacent to the Nikwasi Mound, an ancient Mississippian period (800-1600 CE) ceremonial mound. The UST site’s location adjacent to the Little Tennessee River, the historic Cherokee Nikwasi Town, and Nikwasi Mound, made achieving cleanup that much more significant.

In 2015, a cleanup activity was conducted by the NC Petroleum Storage Tank Fund. USTs across the site were removed along with 3,200 tons of contaminated soils. Because of the site’s sensitivity as part of Nikwasi Town, the work was monitored by the Tribal Historic Preservation Office of the Eastern Band Cherokee to ensure that no materials of archaeological significance were disturbed. During the remediation process, it was discovered that the oil company sat on over 13 feet of fill laid down by floods and development. As a result, the original Cherokee townsite had been protected from both development and contamination. The UST and impacted soils were able to be removed without affecting the historic Nikwasi Town and Mound. This former UST site is now a greenspace and visitor’s center, with a connection to the riverfront, native plantings, a rain garden, and repurposed above-ground storage tanks that serve as educational art pieces and reminders of the site’s industrial history (McRae, B. and Phillips, M. 2016).

Brownfields Cleanup Grants

While many clean-up projects will be self-implementing and some will require a level of public-private partnership, others will have a high clean-up cost and low property value. These properties are unlikely to be of interest to private sector developers without public sector involvement. These properties are often large industrial sites that may have been previously assessed, but the cost of cleanup is still much higher than the value of the property and the property is essentially “under water." Brownfields Cleanup Grants are available from EPA through a competitive grant application process. Eligible entities include municipalities, quasi-public organizations, such as authorities, and tribes. The applicant must own the brownfield and be able to document that they did not cause the property to be contaminated. This is typically confirmed through Phase I and II ESAs. The applicant must be able to execute the cleanup plan and have a plan to reuse the property once cleanup has been accomplished.

Types of contamination that can be addressed through cleanup grants ranges widely, similar to the RLF program. Petroleum contamination that is not remediated by a petroleum storage tank program is one scenario for which these funds can be used. Use of cleanup funds for petroleum products may be considered when petroleum is mixed in with other contaminants or is present as a result of industrial, rather than fueling, operations. Asbestos and lead-based paint as well as mold are common indoor contaminants remediated using cleanup grants. Controlled substance spills, such as methamphetamine labs, and animal debris can be the subject of a cleanup grant. Animal debris may be present in older buildings with uncontrolled access resulting in large deposits of pigeon, bat, or other excrement as well as animal carcasses which pose an environmental hazard to humans. Mine-scarred lands and contaminated industrial sites are also possible recipients of cleanup funds.

In Little Rock, Arkansas, the Arkansas Inland Maritime Museum obtained the USS Hoga tugboat for a hands-on exhibit space. After many challenges, the museum was able to have the tugboat delivered to its location on the Arkansas River by barge. The USS Hoga had a storied history and was one of two ships that remain from the Pearl Harbor attack. The ship was credited with saving the entire Pacific Fleet during the attack on Pearl Harbor by supporting sinking ships and allowing others to escape. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1989 (Arkansas Inland Maritime Museum, 2018).

Prior to making the ship open to the public, cleanup of hazardous materials onboard would have to be conducted. A cleanup grant was sought from EPA for activities on the USS Hoga. However, the federal law states that a brownfield is “real property.” “Real property” is typically land, and specifically land with a legal property description. As a ship, the USS Hoga did not qualify as a brownfield regardless of its environmental condition. A solution to the “real property” question was found by working with the Arkansas State Historic Preservation Office and having a state historic preservation easement established. This provided the ship with a legal property description. And with a legal description in hand, a grant for cleanup was pursued again, and awarded. Cleanup of asbestos, lead-based paint, and other hazardous material was conducted in coordination with the Historic Preservation Commission. The ship is now open to visitors at the Arkansas Inland Maritime Museum.

Summary

Targeted Brownfields Assessments, Revolving Loan Funds, Petroleum Storage Tank Funds, and Brownfields Cleanup Grants are a few of the financial tools that are available to preservationists seeking to address environmental contamination. Success stories from across the country are available showing how even technically difficult sites and programmatically challenging situations have been addressed, resulting in cleanup and redevelopment.

References

Arkansas Inland Maritime Museum. 2018. http://aimmuseum.org/uss-hoga/. Accessed March 14, 2018.

Oklahoma Department of Commerce. 2008. Chiappe, J.; Busch, C.; Craig, M.; Mauldin, S.; Smaokhvalova, S.; Crofford, L.; Pint, D.; and Appleton, A. The Economic Impact of Oklahoma Brownfields Program, Oklahoma Department of Commerce, Research and Development Services. 2008.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2009. “Along Route 66, Cleaning Up the Reminders of an Historic Road’s Former Glory, Brownfields Success Stories along Historic Route 66.” USEPA Department of Solid Waste and Emergency Response Publication EPA-560-F-09-018. February 2009

EPA. 2014. Pinkey, J. “EPA Awards City of Wilson, NC and the Upper Coastal Plain Council of

EPA. 2017a “Overview of the Brownfields Program” https://www.epa.gov/brownfields/overview-brownfields-program, November 17, 2017

Governments a total of $1.4 Million to Assess and Clean Up Contaminated Sites.” June 3, 2014.

EPA, 2017b. “Cleaning Up Underground Storage Tank Releases.” https://www.epa.gov/ust/cleaning-underground-storage-tank-ust-releases, November 28, 2017.EPA. 2017c. Breen, B. “Brownfields Revolving Loan Fund Success Stories: Oklahoma City, Oklahoma” July 3, 2017.

EPA. 2018. “Targeted Brownfields Assessments (TBA).” https://www.epa.gov/brownfields/targeted-brownfields-assessments-tba, January 22, 2018

McRae, B. and Phillips, M. October 26, 2016. The Franklin Press. “River Rises as New Focus.” http://www.mainspringconserves.org/press-room/franklin-press-river-rises-new-focus/

National Endowment for the Arts. Exploring Our Town. Wilson, NC Vollis Simpson Whirligig Park. https://www.arts.gov/exploring-our-town/vollis-simpson-whirligig-park. Accessed March 10, 2018.

Symposium

You can read other articles from the proceedings of Are We There Yet? Preserving Roadside Architecture and Attractions, April 10-12, 2018, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Or explore other content from the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training (NCPTT).