Last updated: June 7, 2021

Article

Bronze Tablet at St. Paul's Recalls Union Veterans & Patterns of Civil War Memory

National Park Service

& Patterns of remembrance of the Civil War

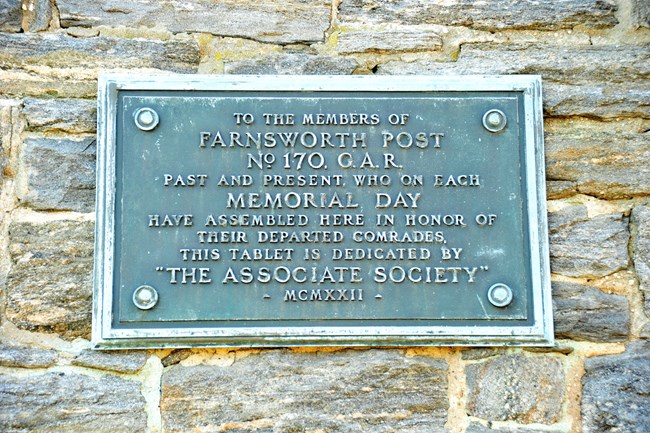

A small bronze plaque bolted into the masonry at the eastern side of St. Paul’s Church commemorates the earlier gatherings of a local Union Army veterans’ group and also leads to an understanding of the remembrance of the Civil War when the tabled was installed in 1922.

The immediate need for the tablet was the passing away of the generation of former soldiers who sustained the Farnsworth Post New York 170 of the Grand Army of the Republic, the major Union veterans’ organization. Centered in Mt. Vernon, the Farnsworth post also drew membership from surrounding communities in southern Westchester County and the northern Bronx, about 20 miles north of New York City. With three centuries of American history preserved on the church grounds, St. Paul’s emerged as a logical site for the group’s annual recognition of Memorial Day, created in 1869 to honor Union soldiers. By the early 1920s, death through natural causes had greatly reduced the ranks of the Farnsworth men who had staged the commemorations.

The Farnsworth Post of the G.A.R. was founded in 1880. Fifteen years after Union victory, this was a time of great expansion for the veterans’ group all across the North -- memories of the horrors of the war had faded; yet, recollections of shared commitment and sacrifice remained strong. Enlisting 175 members, the chapter sponsored a myriad of fraternal activities and social services among members -- free medical care and medicine, cash relief payments and services, burial costs, financial assistance to widows and orphans, free coal or firewood. The advantages of membership are reflected in the large number of veterans who served in regiments from other states and joined the Farnsworth group upon relocating to the St. Paul’s vicinity in the late 19th century.

Memorial Day exercises at St. Paul’s symbolized the bond between the living Farnsworth men and the dead Union veterans. With eighteen members of the post buried in the five acre cemetery, the church functioned as the group’s spiritual fulcrum. The unit’s history recalls that “the muffled drum beat on Memorial Day, is heard but faintly, though with reverence, as the members of the Farnsworth Post wend their way once more to the graves of comrades who have gone before.”

The theme of “gone before” underscored the motivation behind the installation of the plaque by a group designed to recall the Farnsworth post and the service of Union veterans. It was the Associate Society of the veterans post. Organized in 1897, the unit’s establishment paralleled the formation of these support organizations for posts across the North. The original G.A.R. members were passing away and there were concerns about perpetuating the memory of the role of the veterans’ organizations and the service of the Union soldiers.

According to the guidelines, the associate society was intended “to stimulate patriotism and a grateful remembrance of the blessings secured to the nation by the happy termination of the War of the Rebellion.” Associate club members, who were not soldiers in the war of 1861-1865, paid sizable annual dues which financed the activities of the GAR posts. They were often successful businessmen and prominent civic leaders who doubtless respected the benevolent role of the post in supporting the veterans and welcomed the opportunity to help preserve the legacy of their service in the war. Additionally, these men appreciated the personal and professional advantages gained through connection to a well-regarded, highly organized constituency of veterans whose ranks included five Presidents of the United States. Yet, by 1922 these indirect rewards of Associate club membership had probably declined because of the fading relevance of the G.A.R.

The keynote speaker at the dedication of the small, rectangular metal plaque reflected this profile of associate society members. It was silver haired, former State Supreme Court Judge Isaac N. Mills, an enormously influential political figure in the early history of Mt. Vernon. Born in 1851, he was too young to bear arms in the struggle, but would have experienced the war as a young civilian on the home front. He had attended Memorial Day commemorations at St. Paul’s since the early 1880s. (Judge Mills died in 1929 and is buried at St. Paul’s, about 20 yards from the tablet he helped dedicate seven years earlier.)

On a Tuesday morning, when Memorial Day was still recognized on the traditional holiday of May 30, visitors representing civic and patriotic organizations, a few surviving Union soldiers and the general public crowded around the eastern side of the historic edifice to welcome the unveiling of the 15” by 24” tablet. It was located at the point where the Farnsworth men assembled. A member of the Associate Society since its founding, Judge Mills outlined five reasons “that no war in the history of time has left such a memory as the civil war.” Mills’ talk delineated the illegality of Southern secession in 1860/1861; the necessary and just cause of upholding the political and territorial integrity of the Union; the inevitability of the resort to arms as the sole course for confronting the issue of secession; the martial efforts and ultimate success of the Union army, and the nation’s peace and prosperity in the decades since 1865.

There was, strikingly, no mention of slavery as a cause of the war or emancipation as a consequence of the struggle, an indication of the contemporary, collective memory of the North. Themes which animated the political confrontations of the postwar Reconstruction era -- concerns about civil rights and economic progress for the freedmen, and altering the political and economic conditions of the South -- had long since vanished from the public debate. The paramount national requirement of reconciliation between the sections as the proper course for preserving and developing the Union in the late 19th century had eclipsed earlier understandings of the significance and legacy of the war. On Memorial Day 1922, nearly 60 years after the Confederates’ surrender, a widely respected jurist and scholar discussed the Civil War without any reference to slavery or racial issues.

But those cross currents about the significance of the Civil War were certainly not integral to the sense of anticipation and imagination enlivening the assemblage on the edge of the historic cemetery. Basking in the sunshine, with temperatures in the mid 80s, the 300 people crowded around the southeastern side of the stone church doubtless thought they were privileged to secure a first glimpse of a memorial installed to insure that posterity would recall the annual gatherings of the Farnsworth post on a day set aside to remember Union veterans. Through a reasonable extension, they recognized the plaque would help preserve the record of the sacrifice and service of the young men who had helped sustain the republic at its greatest hour of peril.

The tablet, pictured above, reads:

TO THE MEMBERS OF

FARNSWORTH POSTNo. 170 G.A.R.

PAST AND PRESENT, WHO ON EACH

MEMORIAL DAY

HAVE ASSEMBLED HERE IN HONOR OF

THEIR DEPARTED COMRADES

THIS TABLET IS DEDICATED BY

“THE ASSOCIATE SOCIETY”

MCMXXII