Last updated: March 8, 2025

Article

Bridging Boundaries to Protect Migratory Birds

U.S. national parks are part of an international network tracking vulnerable migratory birds. They are also vital training grounds for future bird conservationists.

By Sarah Milligan, Sarah Stock, Steve Albert, and Dave Treviño

Image credit: NPS

Each year, some 350 species of North American birds make the long, arduous journey from their breeding grounds in the United States or Canada to overwintering areas in Central or South America and then back again.

About half of North America's birds spend most of the year south of the U.S. border. The National Park Service’s mission to protect and preserve animal species on land it manages is made more complex when they only spend a short time there. This task is further complicated when there are gaps in our understanding of the migration pathways they take. What are the critical places along the way where they rest and refuel? Where do they spend the winter months? To answer these questions, the agency works across international boundaries to share technologies, techniques, and information. In the process, it also helps train future conservationists.

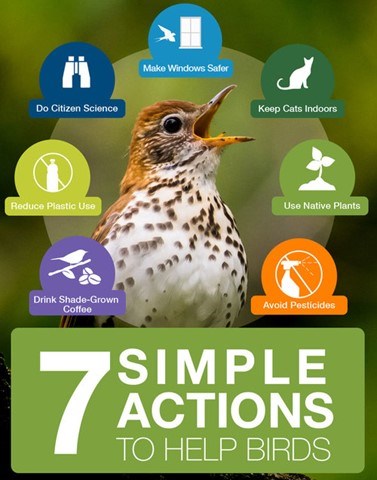

How to Stop Our Wild Birds from Disappearing

A recent study showed there are almost three billion fewer birds in North America today than in 1970. This is an overwhelming statistic, but there are some things we can do to stop this decline. Here are some tips with links to short videos from Cornell University's ornithology lab. Right-click on each link to open in a new tab or window:

- Make windows safer

- Keep cats indoors

- Plant native plants

- Avoid using pesticides

- Drink shade-grown coffee

- Reduce plastic use

- Do citizen science

Image credit: NPS

A Legacy of International Cooperation

The National Park Service has a history of working across international boundaries to conduct research and monitor birds. International interns have assisted the agency with monitoring birds over the last several decades. The National Park Service operated the Park Flight Migratory Bird Program from 2001 to 2010 as a cooperative venture between the National Park Service, National Parks Foundation, American Airlines, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, U.S. Agency for International Development, and the University of Arizona. Park Flight helped to conserve shared migratory bird species and their habitats in U.S., Canadian, Latin American, and Caribbean parks and other protected areas. It did this through conservation and education projects and exchange of technical information. In the nine years Park Flight was in operation, 85 international interns from 19 countries participated. Many of those individuals are now leaders in bird conservation in their home countries.

Studying the summer or breeding portion of a bird’s life is only half the story.

In 1989, the Institute for Bird Populations initiated the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) program. This collaborative program enlists public agencies, non-governmental groups, and individuals to band birds and study their health demographics (population sex and age structure; how well individuals reproduce and survive over time). Participants gather data through a network of MAPS stations. At each station, a cooperating partner uses mist nets to capture and band birds during the breeding season. They also collect information on the birds’ health, age, sex, molt condition, and other factors. The National Park Service installed the first stations in Yosemite National Park. Since then, nearly 40 units of the National Park System have operated or supported more than 120 MAPS stations. The information gathered by program cooperators helps scientists understand which life stages may be most important in affecting population growth. It also helps answer questions such as what causes population declines and which areas have the worst problems.

But studying the summer or breeding portion of a bird’s life is only half the story, so the institute began the Monitoring Overwinter Survival (MoSI) program in 2002 to study avian health and demographics in non-breeding areas south of the U.S. border. Using methods similar to those employed by MAPS, the MoSI program now operates nearly 100 stations in more than 20 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. All data from both the MAPS and MoSI programs are free to researchers and the public. Some MoSi participants also visit U.S parks to receive training.

Image credit: NPS

Yosemite Tales: “I Felt Like One, Flying to the North”

There’s a lot more to most national parks than trails, campgrounds, and scenic vistas. A great deal of scientific research goes on in them. Some people love it when there’s a chance to peek in on scientific studies in national parks. Bird banding is a perfect way for people to get a window into park research. MAPS and MoSI have an internship program to bring a MoSI-affiliated early-career biologist to Yosemite National Park each year to work with the park’s MAPS crew. Over the past few years, banders from Nicaragua, Mexico, Peru, and Belize have visited Yosemite to exchange expertise.

Yosemite is celebrating 32 years of songbird banding, making it the longest-standing MAPS program in North America.

The program was an “incredible way to understand the different types of habitat where migratory birds breed,” said Nicaragua intern Heydi Herrera Rosales. “It broadened my perspective regarding the management of habitats in the tropics. It was fabulous to share professional values such as rigor in field data collection, application of methodologies, and knowledge. The great qualities of the National Park Service and [Institute for Bird Populations] staff I worked with was always evident as we shared our cultures and our personal and professional dreams. Migratory birds have no borders, and I felt like one, flying to the north, where I was very warmly received.”

This year, Yosemite is celebrating 32 years of songbird banding, making it the longest-standing MAPS program in North America. This ongoing monitoring continues to fulfill Yosemite’s larger goals of protecting birds through science and giving young people and visitors hands-on experience in wildlife conservation. Project scientists publish papers on long-term trends and the effects of climate change on songbirds. This information helps park management develop data-driven restoration projects, like the one for Ackerson Meadow, which protects and enhances habitat important to meadow birds. The park’s philanthropy partner, Yosemite Conservancy, has provided vital funding for the park’s songbird research program since its infancy.

When Grosbeaks Go "Backpacking"

In June 2014, Yosemite’s bird crew captured nine black-headed grosbeaks in Hodgdon Meadow. The crew equipped the migratory birds with tiny “backpacks” carrying archival GPS devices that collect data showing the pathways the birds take. Then they released the birds. To study the data, biologists would have to retrieve the birds and their backpacks. Black-headed grosbeaks, which summer in Yosemite but head south during the winter, tend to return to the same places each year. In June 2015, the bird crew found a backpack-wearing grosbeak in a MAPS net at Hodgdon Meadow. The crew retrieved the GPS device, which allowed scientists to map the grosbeak’s journey.

The device showed that after leaving Yosemite, the grosbeak had paused in Sonora, Mexico, for several weeks. It then traveled farther south to its winter grounds. That route points to a “molt-migration” pattern, meaning the grosbeak arrived in Sonora when ample food was available and paused there to shed its feathers before continuing. When the bird crew recaptured a second backpack-bearing bird in June 2016, the GPS data showed it had flown a similar path.

Knowing that the black-headed grosbeak is a molt-migrant opens the door for a discussion about its future. Climate change could lead to a mismatch between the grosbeak’s migration schedule and its ability to obtain food at various stopping points. The grosbeak’s story underscores why Yosemite’s bird-banding research matters well beyond park borders. The bird’s journeys and demographics provide important clues to environmental changes in Yosemite, in the Sierra Nevada region, and across the western United States.

Image: Black-headed grosbeak wearing a backpack with GPS archival tag prior to release in Yosemite National Park. Courtesy of Chris Hubach.

Image credit: NPS

"Being Part of a Flock” at Bandelier

Inspired by the successes of other parks, Bandelier National Monument installed its first MAPS station in 2004. International interns from Mexico, Columbia, and Ecuador have over time assisted the park in capturing and banding birds. The banding stations help the park answer the question, “How are our feathered friends doing around the world?” The stations collect demographic information such as bird reproduction and survival rates. The monitoring program targets many migratory species who summer in the park and winter south of the border. For this reason, the park prioritizes hiring international interns who come from Central and South America. The interns appreciate connecting with birds who spend their winters in the same place they call home.

The initial MAPS station in Bandelier was set up to train international interns to study dark-eyed junco movements. The park added three banding stations in 2010 and a fourth in 2017. With more stations, the park could track additional trends in bird populations, such as those related to climate change and wildfire. The park has been able to track several species “of greatest conservation need” as determined by the U.S. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. Many of these thrive in Bandelier’s post-fire habitat. They include western and mountain bluebirds, pygmy nuthatch, and Virginia’s warbler. Populations of all four species have increased in the park since the 2011 Las Conchas Fire.

"Could be great to collaborate on a Bandelier-Veracruz program, because the birds join us and don't know borders!"

Image credit: NPS

In the last few years, Bandelier has turned its attention to expanding its public outreach within surrounding communities. Bandelier’s international interns play a critical role in hosting school programs for 4–6 graders (including in local Pueblos) every September. This program sponsors more than 20 classes each year. The interns give a presentation at the school then guide the classes on a field trip to the banding site to see scientists in action. In 2021, during fall migration, the park invited the public on ranger-led “bird-banding days” to learn more about birds, their migration, and their health at Bandelier’s bird-banding stations.

“Being part of a flock is the feeling I remember with special gratitude from my days at Bandelier,” said former international intern Diana Balbuena. “Now I am working at [Pronatura Veracruz A. C.] doing bird monitoring and contributing to restoration projects, some of them related to enhancing bird's habitats. Could be great to collaborate on a Bandelier-Veracruz program, because the birds join us and don't know borders!”

Shaping the Future

Monitoring programs can give us insight into how public land management practices are affecting birds. They are also important for understanding the effects of climate change and other widespread threats. Although parks act as a refuges, we must consider the full annual cycle of wild birds to effectively conserve them. When the National Park Service works long-term and consistently with U.S. and international partners to identify key breeding, overwintering, and stopover sites, we help ensure the future vitality of our migratory bird populations. We also empower the next generation of international bird conservationists.

About the authors

Sarah Milligan manages the Natural Resource Program at Bandelier National Monument. Image courtesy of Sarah Milligan.

Wildlife Ecologist Sarah Stock leads the Terrestrial Wildlife Program at Yosemite National Park. Image credit: NPS

Assistant Director for Demographic Monitoring Programs Steve Albert works for the Institute for Bird Populations. Image courtesy of Steve Albert.

Wildlife Biologist Dave Treviño works for the Washington Support Office of the National Park Service. Image courtesy of Dave Treviño.