Last updated: September 22, 2022

Article

What the Campaign Left Behind: The Aftermath of Brandy Station

Though the Battle of Brandy Station is remembered as the largest cavalry engagement of the American Civil War, discussion of the aftermath of this incredible event is often lost as the Gettysburg Campaign marched north towards Pennsylvania.

Much like soldiers, homes, churches, and communities also became casualties of the fighting that took place in, around and through them. Many of these historic structures retain strong associations with actions that raged around them, like the Dunker Church at Antietam and the Trostle Farm of Gettysburg. Brandy Station is no different. Its fields saw great loss of men, horses and mortar alike and were certainly no stranger to the armies of blue and grey. One small, red brick building nestled on a plateau of this landscape would bear witness to the realities of war and campaign in the spring of 1863. Its story is a reminder that the destruction of war doesn’t discriminate.

Nearly twenty thousand horsemen clashed on fields and hillsides just northeast of Culpeper, Virginia on June 9, 1863. After the engagement there were nearly 1,300 men killed, captured, wounded, or missing from their ranks. Captain William W. Blackford, an aide of General J.E.B Stuart remembered the carnage, later writing “Fleetwood Hill was covered so thickly after the battle with dead horses and men that there was not room to pitch the tents among them.” Union soldier Morris Schaff would later recall an evening he spent on the battlefield of Brandy Station, writing, “my tent at the station, pitched after dark and partly floored, I discovered later was over the grave of someone who had fallen in those repeated charges.”[1]

Confederate troopers got to work “to bury friend and foe alike, precisely where they fell” in the hours after the battle.[2] Men were buried across the battlefields on which they’d fought. A lucky few were later relocated to the Culpeper National Cemetery, where they rest alongside their brothers in arms who fell during battles at Cedar Mountain, Trevilian’s Station, and Gordonsville. The identities of many are unknown.

Another piece of the battlefield that became a resting place for men in both the blue and grey was the St. James Episcopal Church. The church was small, 40 feet by 40 feet and two stories high. It was constructed of red bricks that had been fired on the property by enslaved laborers and was officially consecrated in 1842.[3]

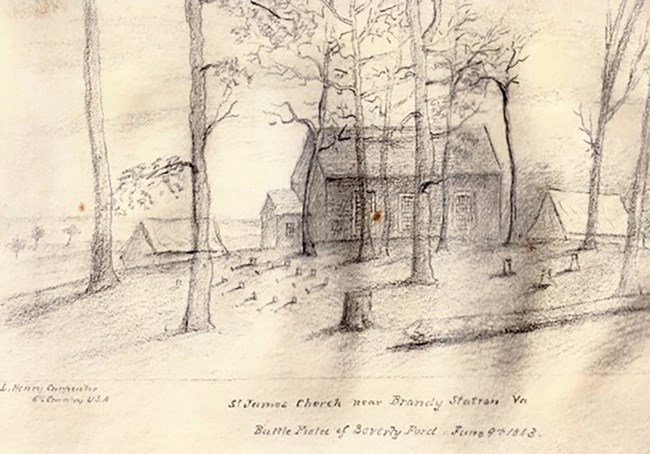

During the June 1863 battle it became a Confederate artillery position and witnessed a horrific struggle when the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, and 6th U.S. Cavalry attempted an unsuccessful charge on the guns. Its grounds became the final resting place for a number of those who fell during the battle. Though two marked graves remain at the site today, there’s no official record detailing each interment on the property. Until recently, there was also no known rendering of the original St. James Episcopal Church.

The original building became a casualty of the Civil War, much like the men who fought in the fields around it. During a heated artillery exchange in 1862, some of the church pews were removed for the burial of Confederate dead.[4] During the winter encampment of 1863-1864, the Army of the Potomac returned to the hallowed landscape of Brandy Station. The church was deconstructed by soldiers to build chimney stoves for their winter quarters, the red bricks able to withstand the heat of their ever-burning fires. Once the army left camp, hardly any presence of the church, which was once described by a Pennsylvania officer as “a modest sanctuary.... suggesting a time back when the woods were the first churches,” remained.[5]

For years, the small clearing in a wooded lot just off St. James Church Road in Brandy Station, Virginia has remained the same for every veteran, historian and visitor that’s paid a visit. Church records and first hand accounts of those who had interacted with the modest brick structure in some way before it’s deconstruction, were the only tools available to keep St. James Episcopal Church from being lost to the war forever.

That was, until, the personal sketchbook of Lt. Louis Henry Carpenter surfaced. Lt. Carpenter of the 6th U.S. Cavalry fought at the Battle of Brandy Station. He was one of the participants in the ill-fated charge of the Confederate guns positioned at St. James Episcopal Church. Along with the 6th U.S. Cavalry, he would go on to serve throughout the remainder of the Gettysburg Campaign. On July 3, as part of Wesley Merritt’s Cavalry Brigade, the regiment would fight on South Cavalry Field in some of the concluding moments of the Battle of Gettysburg, the climax of the very campaign they began here at Brandy Station. Eventually, the war would bring Carpenter and his regiment right back to the old Battlefield from the previous June to spend the winter.

He was also the artist behind the one known surviving sketch of the church. His timing was fortuitous as the church was torn down that very same winter. The sketch shows an arrangement of graves among a cluster of trees, and the church in the background with two camp tents on either of its sides. Lt. Carpenter has unknowingly given the world a look into 1863, keeping the church from falling entirely victim to the war that came knocking on its door. To Carpenter, this may have just been a memento from a terrible experience in his life, for us, this is the only surviving artistic rendition of the St. James Episcopal Church.

This sketch, and story of the red church that persisted serves as a reminder that the aftermaths and casualties of battles can take on many forms and figures. The lives, homes and fields of many were touched by the American Civil War by June of 1863, and the Gettysburg Campaign was just beginning.