Last updated: February 14, 2025

Article

Boston Marriages

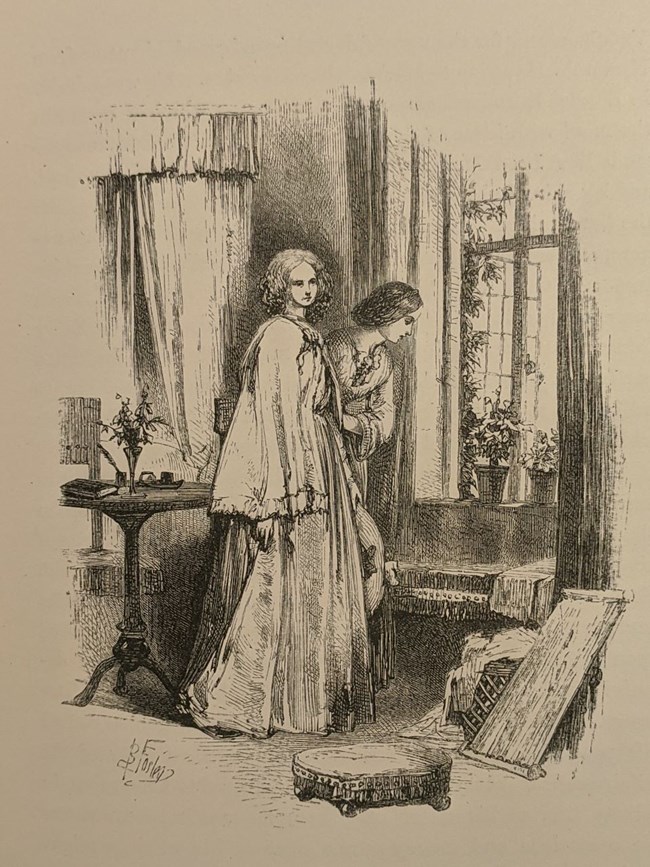

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 15037)

Longfellow’s writing, and that of members of his social circle, provide contemporary audiences a lens on the history of romantic relationships between women in 19th century New England. In 1849, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published the novella Kavanagh. Though hardly his most remembered work, it is notable for one very important reason: The story depicts one of the first lesbian relationships in American fiction.1

The relationship between two of the main characters of the book, Cecilia Vaughan and Alice Archer, appears to have been partly based on the real-life relationship of Longfellow’s friends Charlotte Cushman and Matilda Hays. Much like the male romantic friendships of the era, female romantic friendships were actively encouraged- perhaps even more so- mainly due to the misguided Victorian belief that women lacked intimate sexual desire. Girls were encouraged to kiss, hold hands, share beds, and be openly affectionate, as it was considered good training for marriage.2 Even Longfellow’s wife, Fanny, was accustomed to this social norm. She shared a warm, if platonic, life-long relationship with her best friend, Emmeline Austin. Cushman and Hays, however, hardly fit that mold, as the journals and letters that Cushman left behind are rather explicit about their romantic partnership.3 However, to those not privy to their most intimate moments, the only thing unusual about the two women was their refusal to marry at all.

Longfellow seemed to have understood that, though most romantic friendships ended in a marriage to someone else, the love that the participants felt was just as genuine as that between a husband and wife. In the story, the romance between Cecilia and Alice is placed on equal footing with the romance between Cecilia and her other suitor, Kavanagh. Though in the end Cecilia does marry Kavanagh, Longfellow portrayed the women’s relationship with surprising delicacy and understanding. Even today, Alice’s first realization that she is in love with her best friend resonates

Was it nothing, that among her thoughts a new thought had risen, like a star, whose pale effulgence, mingled with the common daylight, was not yet distinctly visible even to herself, but would grow brighter as the sun grew lower, and the rosy twilight darker? Was it nothing, that a new fountain of affection had suddenly sprung up within her, which she mistook for the freshening and overflowing of the old fountain of friendship, that hitherto had kept the lowland landscape of her life so green, but now, being flooded by more affection, was not to cease, but only to disappear in the greater tide, and flow unseen beneath it? Yet so it was; and this stronger yearning — this unappeasable desire for her friend — was only the tumultuous swelling of a heart, that as yet knows not its own secret.4

Though Longfellow wrote one of America’s first documented lesbian relationships, a more enduring one was written by another man in Longfellow’s circle, Henry James. In 1886, James published the novel The Bostonians. Despite never using the term directly in the text, the novel popularized an enduring term in gay history: “Boston Marriage.” Boston Marriages were a newer concept in the second half of the 19th century, owing its meaning to the women involved in them. Women in these marriages were often from New England, college-educated, financially independent, and with careers of their own.

By the late 19th century, some women began to gain more opportunities outside the home. This new era of freedom meant opened up the possibility that women could spend the rest of their lives with one another, without the need for a traditional marriage. Many of these women formed intense, life-long committed relationships with one another as a result.5 However, class constraints meant that most women in this time were still expected to marry and have children no matter what their sexuality was.

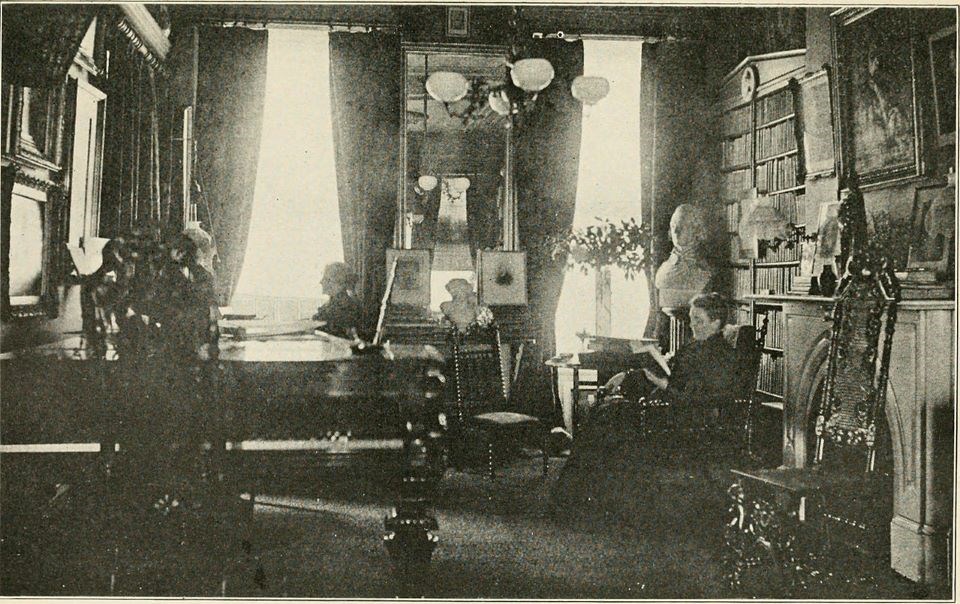

Longfellow Family Photograph Collection (3007.001/002.002-#16)

Though Cushman and Hays are arguably the best early example of a Boston Marriage, few exemplify what a Boston Marriage was more than Longfellow’s friend Annie Fields and her partner, Sarah Orne Jewett. After all, it was Fields and Jewett who served as the inspiration for James’ The Bostonians.6

Annie Fields was the wife of James T. Fields, Longfellow’s publisher. The two had married in 1854, and the marriage by all accounts was one of genuine love and affection. In their time together Annie Fields was renowned for her abilities as a hostess, and she formed close friendships with many of her husband’s clients, including Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Along with hosting popular literary salons in Boston, Fields developed publishing skills of her own. She had a natural talent for spotting literary up-and-comers, and James Fields consistently published authors that Annie recommended. Annie Fields’s keen eye turned unknowns into international sensations, from discovering Emma Lazarus to mentoring Henry James. Her most significant personal discovery, though, was a poet and novelist named Sarah Orne Jewett. The two women instantly connected and became close friends.

When James Fields died in 1881, Annie Fields was beside herself with grief and withdrew from most of her social circle for some time. The one person in whom she found solace was Jewett, who supported her through her bereavement. During this period of time, the friendship blossomed into a romance. When they returned to Boston together later that year, Jewett gleefully wrote to her friend, John Greenleaf Whittier, “We are perfectly delighted to find that you are really going to spend the winter in town and Mrs. Fields says she is going to try to make you promise to come one certain day every week to breakfast (besides every other day you can!) and then we shall be sure of you. I say ‘we’ because I hope I shall be at 148 Charles St. very often indeed.”7

Published in Howe, Memories of a Hostess (Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1922)

“Very often indeed” unsurprisingly, turned into “forever”. For the next 30 years, until Jewett’s death, the two lived together, splitting their time between Fields’s house in Boston and Jewett’s home in Maine. They constantly travelled throughout the United States and Europe, and on the rare occasions when the two were apart they wrote one another daily. The literary salons eventually returned, and the two hosted some of the most famous writers of the day.

Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett appear to have considered themselves married in most every sense, even giving one another rings and reciting vows. On their one year anniversary of those vows, Sarah wrote Annie an unpublished love poem, “Do You Remember, Darling”, reaffirming her commitment to the relationship.

Do you remember, darling

A year ago today

When we gave ourselves to each other

Before you went away

At the end of that pleasant summer weather

Which we had spent by the sea together?

How little we knew, my darling

All that the year would bring!

Did I think of the wretched mornings

When I should kiss my ring

And long with all my heart to see

The girl who gave the ring to me?

We have not been sorry darling

We have loved each other so-

We will not take back the promises

We made a year ago-

And so again, my darling,

I give myself to you,

With graver thought than a year ago

With love that is deep and true.8

Notes

1. Charles C. Calhoun, Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life (Boston: Beacon Press, 2004), 196-197.

2. John D’Emilio and Estelle B. Freedman. Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America, 126

3. Julia Markus, Across an Untried Sea: Discovering Lives Hidden in the Shadow of Convention and Time (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000).

4. Longfellow, Kavanagh: A Tale (Boston: Ticknor, Reed, and Fields, 1849), 83-84. https://archive.org/details/Kavanagh_201407/page/n85/mode/2up

5. Teresa Theophano, "Boston Marriages" (glbtq, inc., 2004). http://www.glbtqarchive.com/ssh/boston_marriages_S.pdf

6. Josephine Donovan, "The Unpublished Love Poems of Sarah Orne Jewett," Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 4, no. 3, Lesbian History (Autumn, 1979): 26-31.

7. Letter, Sarah Orne Jewett to John Greenleaf Whittier, October 19, 1882, quoted in Terry Heller, ed., “Diaries and Letters of Sarah Orne Jewett.” Jewett Texts. http://www.sarahornejewett.org/soj/let/let-cont.html

8. Josephine Donovan, "The Unpublished Love Poems of Sarah Orne Jewett," Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 4, no. 3, Lesbian History (Autumn, 1979): 26-31.