Last updated: January 21, 2026

Article

Table Mountain Pine at Bluffs Lodge, Doughton Park

NPS / Chris Robey

Specimen Details

-

Location: Bluffs Lodge, Doughton Park, Blue Ridge Parkway

-

Species: Table mountain pine (Pinus pungens)

-

Landscape Use: Specimen Tree

-

Age: 80 years old (estimated)

- Condition: Good

- Measurements: 20” DBH (estimated); height undetermined

Introduction

The Bluffs Lodge cultural landscape is a part of Doughton Park and was one of the first developed recreational areas planned for the Blue Ridge Parkway. The entry road, Wildcat Rocks Overlook, and its parking lot were built between 1938 and 1939. The lodge was built about ten years later, opening on September 1, 1949.

The features of the open meadow, with its rolling topography and scattering of trees, rhododendron, mountain laurel, and azaleas are distinctive among parkway landscapes. This natural setting figured prominently in the siting of the Lodge and associated development. Today, the site still reflects the rustic style of park design characteristic of early Parkway development, and visitors can still directly experience the site's historic character.

History

The first phase of construction at the Bluffs commenced with the construction of the entryway and road leading to Wildcat Rocks Overlook in 1938. This work only included grading, road construction, and construction of the Overlook and its associated infrastructure, however. In 1942, a Parkway Land Use Map (PLUM) for the Bluffs area was completed which specified that several trees, including at least one table mountain pine, be planted near the entrance.

Additionally, a range of herbaceous perennials, including hairy rockcress, coral bells, St. Johnswort, sedums, and Virginia spiderwort – all species endemic to rocky crags in the Appalachians – were specified in order “to create a natural rock garden” along the prominent rock ledges marking the entrance to the Bluffs area.

NPS

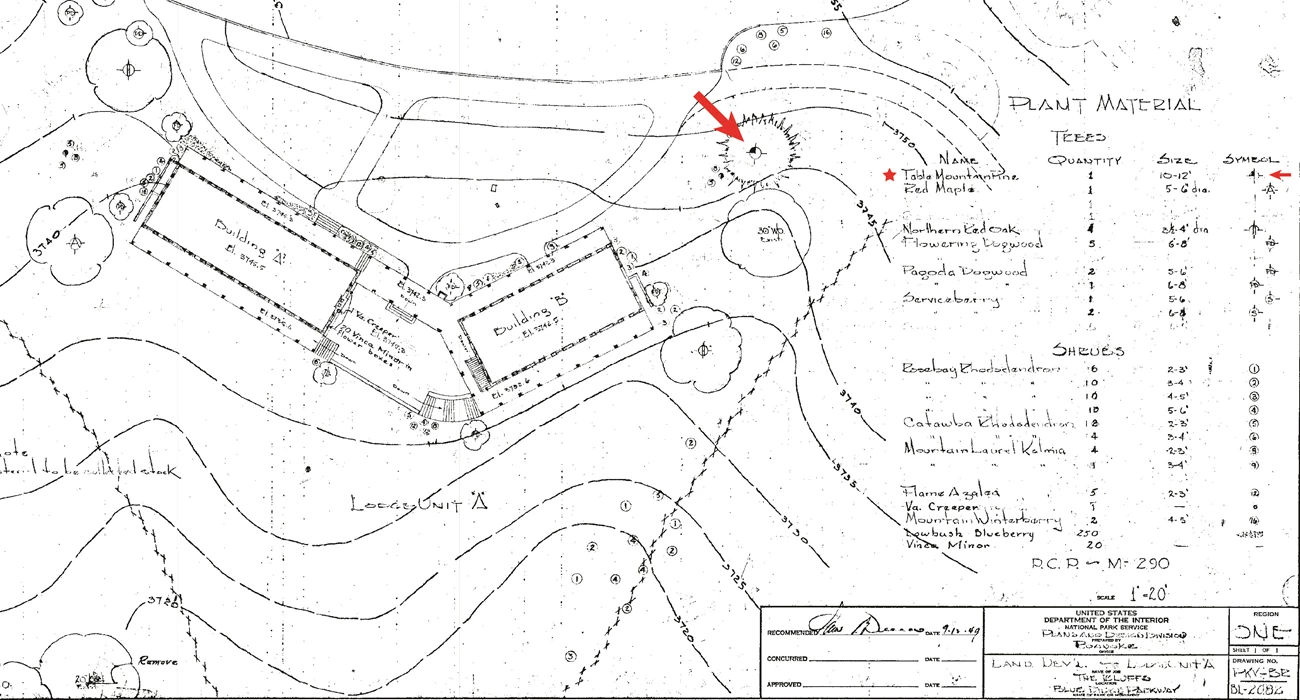

Documentation of designers’ use of table mountain pine as a specimen tree does not pick up again until 1948, when planning for the new Bluffs Lodge complex was well underway. Initial site plans indicate that, prior to the Lodge’s construction, a scattering of existing trees graced the hillside into which the building was to be set, including a white oak, two black locusts, a red oak, an apple tree, and a shadblow serviceberry. The white oak, locust, and serviceberry are still visible in photographs taken at the time of the Lodge’s construction.

NPS

NPS

W.D. Brush, USDA Forest Service, United States, Virginia. Provided By National Agricultural Library

Botanical Details

Table mountain pines are long-lived, slow-growing conifer endemic to the central and Southern Appalachians. It is typically small-statured, rarely growing beyond 66 feet, and exceptionally limby. Its limbs are stout and remarkably strong, earning it the common name “hickory pine.” Their bark is fissured into irregular plates and ranges from smooth to flaky. Their twisted, sharp, rigid needles tend to occur in groups of two.

The epithet, "pungens" refers to the species’ characteristically prickly seed cones. These cones are sessile (meaning attached directly to the branch by its base), broadly egg-shaped, and usually 3 inches long with long with sharp, upward-curved prickles. The cones mature from September to October and can persist on the tree for many years.

Table mountain pines can be notably long-lived, with a maximum age of 250 years. Older trees tend to be flat-topped, while young trees can vary from stout and rounded when open-grounded to slender and small-limbed in forest settings.

Table mountain pines are typically found in open forests on dry ridges, cliffs, and steep southwest-facing slopes. They are mostly found at elevations between 1,000 and 4,000 feet, although the species has been known to occur as high as 5,800 feet. Well-adapted to this austere habitat, table mountain pine seedlings generally anchor their taproot into rock crevices before spreading secondary lateral roots to take up water and nutrients. Other sinker roots descend into additional crevices, utilizing accumulated soil and nutrients drawn from the rock’s surface.

Table mountain pines are also well-adapted to fire. Characteristics like medium-thick to thick bark, a deep rooting habit, self-pruning limbs, and pitch production to seal wounds suggest that this species has adapted to survive frequent, low-severity fires. Serotinous (slow-releasing) cones and the ability to produce viable seed at a young age also allow table mountain pine populations to persist after more infrequent, high-severity fires.

The trees cones provide a year-round source of food for numerous forms of wildlife. The seeds are especially popular with red squirrels, which have been known to harvest a tree’s entire seed crop – if you encounter a table mountain pine with numerous short, stubby limbs, you will know that these persistent rodents have been busy harvesting. The heavy heath layer carpeting the ground in table mountain pine stands also provides plentiful food and cover for other forms of wildlife.

Wood from the table mountain pine tends to be too small and knotty to be of much commercial use beyond pulpwood and firewood. The tree does have a documented ethnobotanical history among the Cherokee, however, who used it for lumber, canoes, and decorative carving.

Perhaps the most vital use of this species, however, is for protecting forests. It stabilizes soil, minimizing erosion and runoff from the vast shale barrens and other rugged topographic features characteristic of its natural range.

Significance

Given the panoply of charismatic flowering and hardwood species that Parkway landscape architects could have chosen as a specimen tree, why would they have chosen this prickly inhabitant of the harshest, most exposed crags of the Appalachians? To answer this question, it is helpful to consider the aesthetic origins of American landscape architecture.

Early landscape design was heavily influenced by picturesque aesthetics, characterized by two main features: (1) “seeing nature with a painter’s eye” and (2) responsiveness to genius loci or “the spirit of the place.” Within the Park Service, this found its ultimate expression in the iconic “Park Service Rustic” style employed by NPS architects, landscape architects and engineers alike. Under the direction of chief landscape architect Thomas Vint, this style became the de facto design aesthetic for projects like the Blue Ridge Parkway.

NPS

NPS

By choosing endemic species like the table mountain pine for landscape plantings, they also sought to evoke a more “naturalistic” feeling. At Bluffs Lodge and Bluffs Picnic Area, the table mountain pine - with its squat, bonsai-like habit and hardy character – was simply the most picturesque choice. J.C. Olmsted, nephew and adopted son of Frederick Law Olmsted, said it best when he declared that a tree “indigenous to the region” would be more likely to evoke “a nearly natural landscape.”

Yet in the attempt to implement a picturesque aesthetic lies a fascinating contradiction; namely, that “harmonizing” a design with the existing landscape is itself an act of artifice requiring that the designer cover their tracks. The designer, in turn, will know that their work is done when park visitors comes away believing that that tree, shrub, or knoll had been there all along – that it was not, in fact, a product of the utmost care and attention to detail.

The palpable feeling that the table mountain pines at Bluffs Lodge have been here all along – and the surprise that comes with learning that it was, in fact, planted - is a yet another sign that the designers’ vision is alive and well at Doughton Park today.

NPS / Chris Robey

Preservation Maintenance

Table mountain pines are fire-dependent. Self-maintaining or non-successional populations of table mountain pine occur and reproduce in the absence of fire on dry exposed ridges and bedrock outcrops where few other species can survive. In a more hospitable climate, table mountain pines tend to be succeeded by oaks and other hardwood communities in the absence of fire.

Southern pine beetle outbreaks periodically kill large numbers of table mountain pines, particularly during drought years. These outbreaks, along with ice storms, windthrows, and other weather-related disturbances, may further hasten succession toward oak dominance.

Where self-maintaining, non-successional populations of table mountain pine are desired, controlled burns could encourage their regeneration and spread. The National Park Service has already worked with researchers at Appalachian State University to recommended controlled burning for maintaining certain viewsheds elsewhere along the Parkway.

As specimen trees, table mountain pines generally do not need much maintenance. Carefully considered pruning may accentuate the tree’s natural windblown, bonsai-like appearance, if desired. As a unique species well-adapted to some of the most austere habitats in the Appalachians, however, the table mountain pines are best left unmanicured.

Indeed, were they alive today, the landscape architects behind the Parkway’s original design might even agree that the table mountain pine is a tree best allowed to display a quiet resilience and dignity hard-won through countless seasons.

Resources

Della-Biana, Lino. “Pinus pungens Lamb. (Table Mountain Pine)” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Bent Creek Forest Experimental Station, https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_1/pinus/pungens.htm

Hamel, Paul B. and Mary U. Chiltoskey. Cherokee Plants and Their Uses -- A 400 Year History, Sylva, N.C. Herald Publishing Company, 1975

Jaeger Company, Doughton Park and Sections 2A, B, and C Blue Ridge Parkway Cultural Landscape Report, National Park Service, Southeast Regional Office, Cultural Resources Division, 2006.

“Pinus pungens (Bur Pine, Table Mountain Pine.” North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, NC State Extension, n.d., https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/pinus-pungens/

Reeves, Sonja. “Pinus pungens.” Fire Effects Information System, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/pinpun/all.html

Spira, Timothy P. Wildflowers and Plant Communities of the Southern Appalachian Mountains and Piedmont a Naturalist's Guide to the Carolinas, Virginia, Tennessee, and Georgia. 1st ed., University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

2075 “Roads, Walks and Parking Area, Lodge” Designed by Van Cleve 12 May 1948; recommended by Weems 26 May 1948 and Allen 15 June 1948; approved by Wirth 6 July 1948

2076 “Lodge Development” Designed by Van Cleve 13 May 1948; no recommendations or approval