Last updated: January 23, 2025

Article

Bicentennial Blues

A lot can happen to a family business in 200 years.

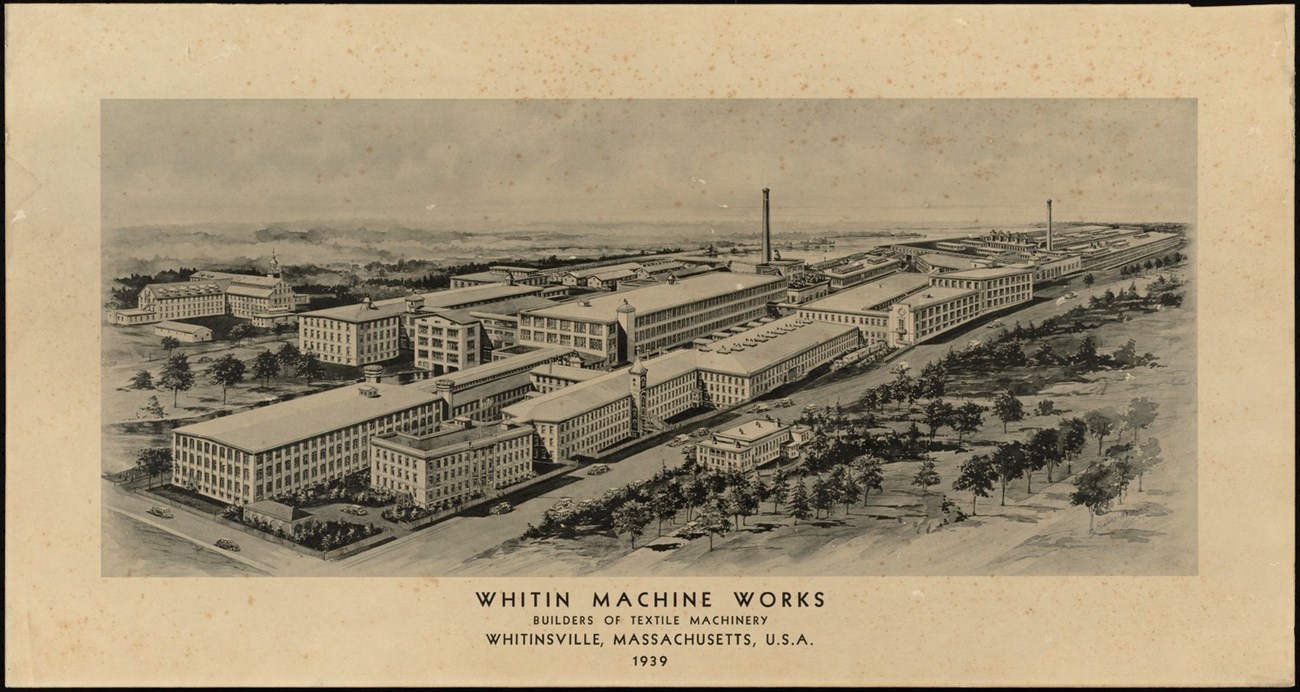

The Whitin Machine Works, based out of Whitinsville, Massachusetts, is a prime case study in the rise and fall of the age of American manufacturing. From a small forge in a rural area, the Fletcher and Whitin families created a veritable dynasty along the Mumford River. Starting with basic tools, heirs to this business made an industrial powerhouse.

Tracing this business’s origins back to the American Revolution, we can see how a company forged during the late 18th century became a supplier of textiles machinery throughout the world. The history of this family-run company, which was shuttered in the same year as the nation’s bicentennial, also prompts important questions about work, freedom, and the legacies of the revolution.

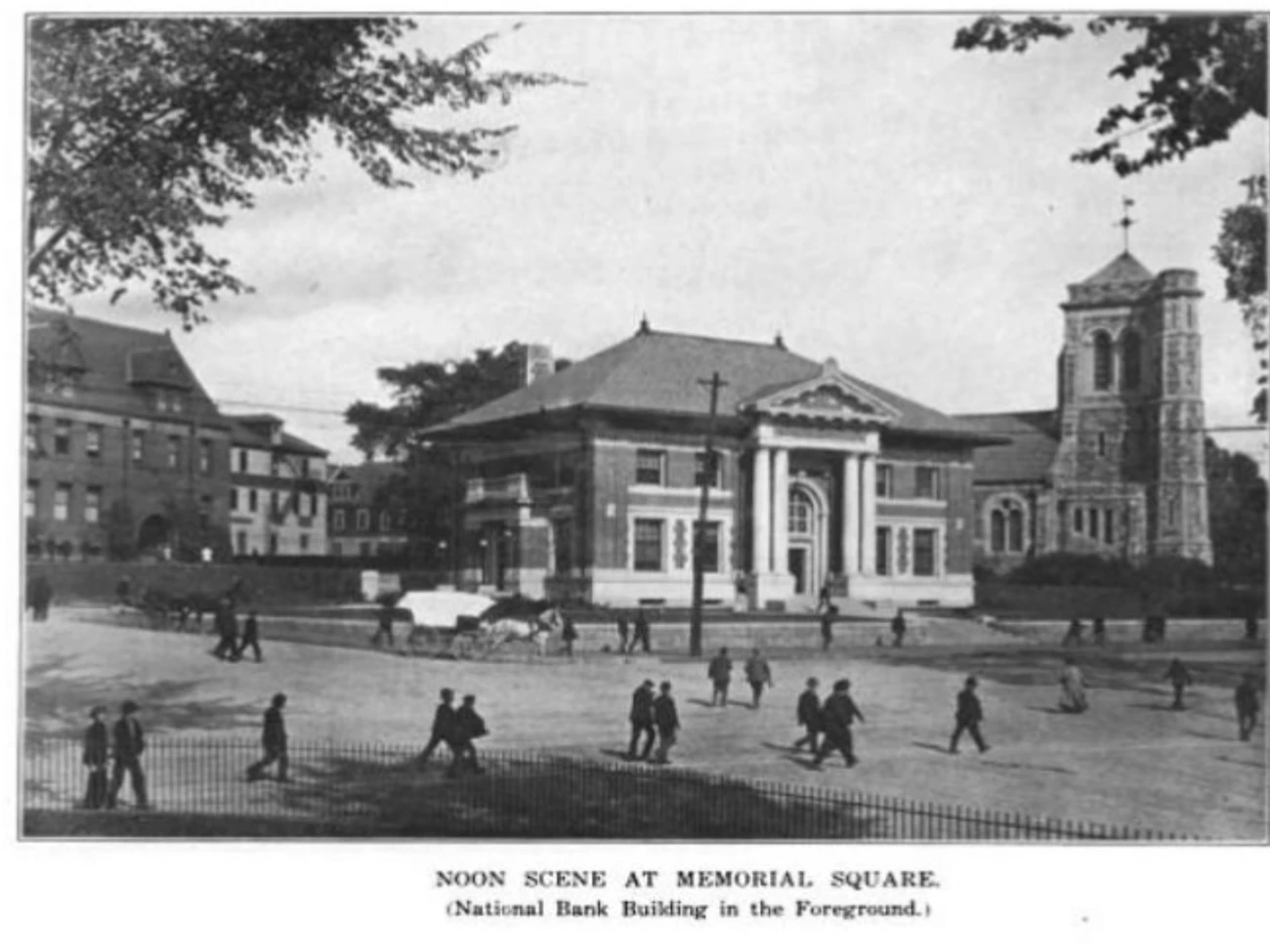

Before there was a place called Whitinsville, and long before it was possible to see a rush of hundreds of workers traveling home for lunch during the mid-day hour, there was just the rush of a small waterfall. The small community that labored there, colonists who had wrested the land from local Indigenous peoples for a too-small price, mostly farmed the land and made small implements to eke out a living. Revolutions were brewing, at first elsewhere, and then at the front doors of these colonists’ small settlements. In throwing off the bonds of one empire, some in this community sought to firm up their own form of rule, in a village that would create a puzzling combination of democratic rule and feudal ownership. Their company would last through the nation’s two hundredth birthday, when the doors closed and foundry fires were extinguished one final time.

This is the story of Whitinsville.

In the early 1770s, James Fletcher set to making tools in a small forge along the Mumford River. Against the rush of the falls, Fletcher had his days punctuated not by a clock, but the rhythm of hammering life into raw iron. The place he called home was marked as Uxbridge on the maps of the time. Fewer than 500 souls lived alongside Fletcher in this community. Within a decade, Fletcher’s loyalties, and many elements in his life, would be totally different.

On the eve of the Revolution, a small push for independence led a cluster of colonists to incorporate a smaller town called Northbridge in the summer of 1772. At that time, Fletcher was newly married to Margaret Wood. Fletcher’s bride was from a well-established family in town. Her father, Ezra Wood, owned rights to the falls on the Mumford River. Soon after their union, the Fletchers constructed a home across from the water. Their compact, classic colonial structure still stands today, now with the address of 1 Elm Place. Living and working along the river, James supported the family through the forge while Margaret ran the domestic industry.

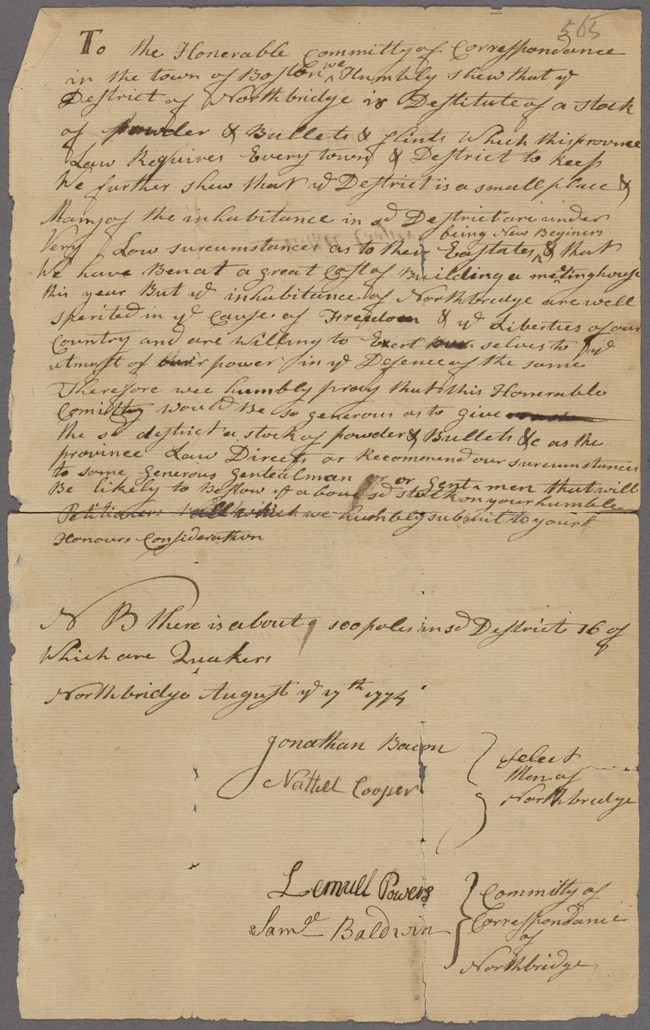

Just two years after incorporation, a far bolder step was taken by local residents. In August 1774, a group of free men formed a Committee of Correspondence.

Earlier that year, the Massachusetts Government Act (May 20, 1774) had called into question the foundation of colonial government not just in small communities such as Northbridge, but across Massachusetts Bay. Under the colony’s charter from 1691, local free people were allowed to call and manage elections for their own government. The Massachusetts Government Act, a targeted attack on this system, revoked the colony’s charter, placing far more power in the hands of colonial governors, who also now had the right to call town meetings. Defying these new restrictions, colonists called meetings of their own and voted to gather weapons. They also refused to import or use English-made goods. It was clear that men such as Fletcher might be leaving the forge behind to work with flints.

During the early days of the war, both Margaret’s father and her husband would be called away for service. She was not alone in this experience. Even in a small community, over 100 men served in the army. All felt the sacrifice of war, as colonists worked to secure the necessary materials to fight one of the most powerful empires on earth.

Fletcher served with Captain Josiah Wood “at the Lexington Alarm” and “was promoted lieutenant, 1776, and served several enlistments in the war.” His father-in-law Ezra Wood served as colonel of the Fourth Worcester county regiment.” Records from applications of the Daughters of the American Revolution and The Massachusetts Society of the Sons of the American Revolution provide further information about Fletcher and Wood. Fletcher can truly be counted among the earliest fighters of the war, for he “marched on the alarm of April 19, 1775 to Roxbury - 9 days.” Fletcher’s intermittent service included time with Colonel Job Cushing from August to November 1777, and additional time with Colonel Nathan Tyler’s regiment from July 1780 to August 1780 (“16 days on alarm at R.I.”).

When the war was over, the work of turning raw and unwieldy matter from the earth into a useful tool resumed for Fletcher. The citizens of Northbridge had been determined to be free from their economic ties to England. They defied coercive acts of legislation, met in secret to stockpile the stuff of war, and they won. What was next? The generation that inherited the American Revolution would have a great deal of influence in answering that question.

In 1777, Margaret and James had welcomed a daughter named Elizabeth to their growing family. Throughout her life, Elizabeth would go by Betsy; in town, her father was now an established figure of his own right, known as Colonel Fletcher. At the age of 16, Betsy started on the path to running her own family. She married Paul Whitin, a man who had been an apprentice for Jesse White, another blacksmith in the community. Paul Whitin originally hailed from Roxbury, MA, where James had traveled to during the early days of the war. Shortly after his marriage to Betsy, Paul began a partnership with the colonel making bar iron. These two unions—of husband and wife, and of business partners–were the start of a long-lasting partnership, forged in blood as well as iron.

While Betsy and Paul were building their life together, there were major changes underway downriver in Rhode Island. Paul and Betsy’s 1793 nuptials took place in the same year that Slater Mill, the first successful cotton spinning mill in the United States, opened for business in Pawtucket, RI. This was a critical step in fulfilling the goal of economically divorcing the new United States from Great Britain. Without local manufacturing and local distribution of goods, the same tethers would persist.

During the War of 1812, when trade ceased between these two nations altogether, the Whitin/Fletcher partnership took on new importance. The two men set their sights on making farm tools, including hoes and scythes. They also started a cotton mill together, catching the “cotton mill fever” of the day. The Whitins’ ten children would expand their father and grandfather’s business operation, making tools and running additional mills for decades.

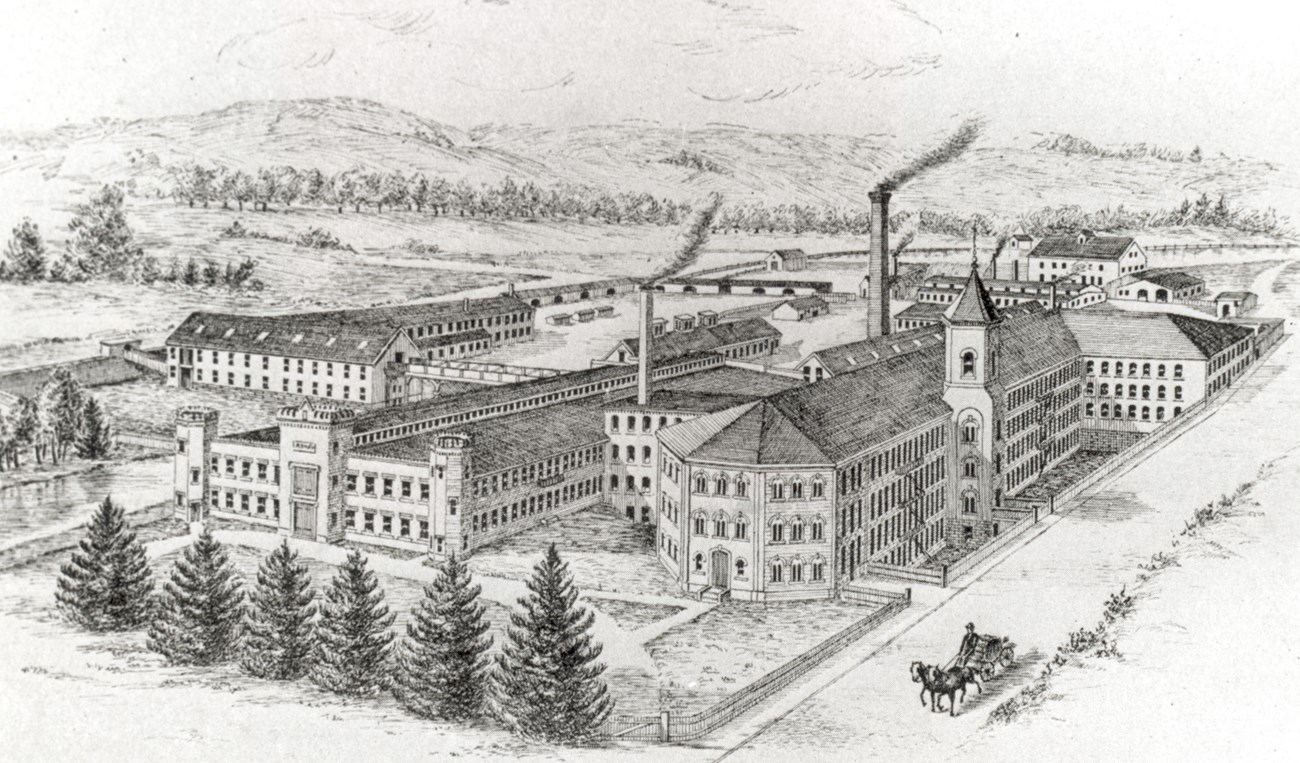

The development of the Cotton Picker, a tool that would put the Whitins and their business on the map, changed the course of history in Northbridge. The creation of this tool spawned greater interest in making the implements of cotton mills. Over time, the Whitins became leaders in making individual parts and machines for highly complex mill operations around the world. Their small forge would be eclipsed by a manufacturing complex that still dominates an entire block and commands nearly 2 million square feet of space.

In the 1800s, from the manufacture of tools, to the construction of mills, to the development of the large machine works, the Whitins kept power and influence all in the family. At the time of James Fletcher’s death in the 1830s, an entire village bore the name of his son-in-law, Paul Whitin. The adoption of the name Whitinsville was an early sign as to the outsized power of this singular family. The Whitins personally invested in the creation of their businesses, but they also put their name to the Memorial Town Hall, a library, a recreation center, and many other buildings in town.

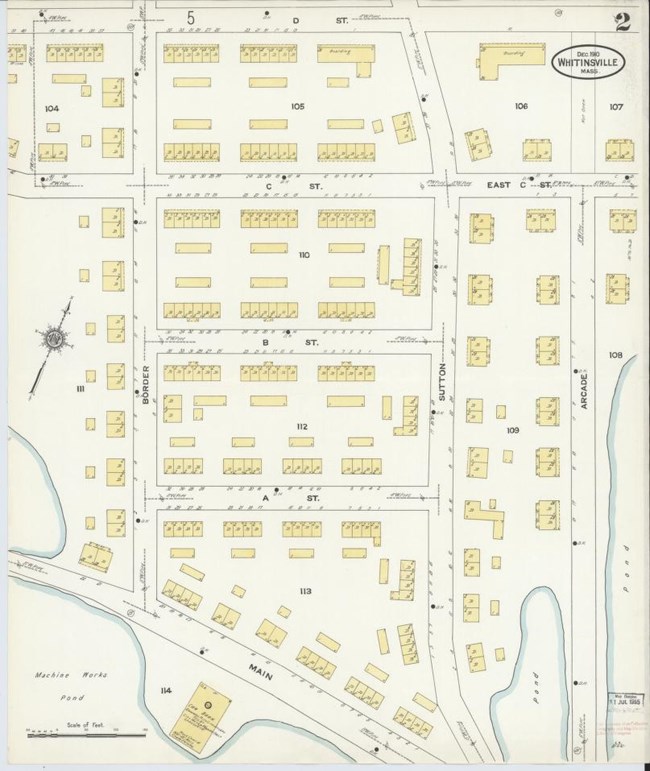

The people who came to live and work alongside the Whitin Machine Works traded total autonomy and control of their craft for relative security. While earning a steady wage and having a place to live (as tenants), the people employed by the Whitins lived under their management at all times. The Whitins commissioned local builders to make approximately 1,000 units of housing for workers. For those fleeing from the Armenian genocide, or looking to start a new life in a foreign land, paying rent to one’s employer, while enjoying an otherwise stable life of wage work, may have felt like freedom. But on this point, not everyone could agree.

In 1919, after citizens from this place went to fight abroad to make the world “safe for democracy,” The Boston Globe did a story on Northbridge. The headline asked “Why do they call it Whitinsville?” Calling the place “a strange principality of happy inhabitants,” journalist Willard F. DeLue describes Whitinsville as a town where a family “dynasty” “has long wielded great economic and political powers.”

“In Europe Kings have fallen and mighty empires have passed into history; but here in Massachusetts, within 50 miles of Boston, the reign of Whitin-Lasell yet holds supreme [.]” For the Whitins and their heirs, “lands and industries are in their hands, and what they do not own they in many cases govern.”

They own the only worthwhile industries here, the only street railway, the only water system, the only fire-fighting department, the only hotel, most of the shores of the only lake, the only local retail coal supply, a tremendous amount of the land, the bulk of the homes. They hold or have held important political offices in the town. They have large interest in the banks. The High School is the "Whitin-Lasell School. And this is only part of the interesting story.

From the fish in the nearby ponds to the foodstuffs served on dinner tables in Whitin-owned worker houses, everyone living in this community had some kind of tie to the company that dominated their community. Earlier members of this village had gone to war over the fact that they might not be able to assemble, vote, and govern themselves. Descendents of Wood and Fletcher, however, were more comfortable with systems that closely approximated autocratic rule. In 1919, DeLue found that in lieu of closed elections, “machine shop men” seemed to run the town and make the decisions. While debates raged over the expansion of women’s suffrage, “both suffs and anti-suffs” were united by being under the “control” of Whitins. On the site of what had once been private family land, a member of the Whitins literally held the keys to what passed for the town hall. The building was in fact “a Memorial Building, privately owned…there are plenty of intelligent persons in Whitinsville who really do not know whether the town or the Whitins own the building.”

While other industrial communities struggled through the economic slumps of the early 20th century, the Whitin Machine Works seemed to thrive. Through World War II, manufacturing boomed in town, not without exception, but with enough regularity to keep some employees for over 60 years.

From the beginning, Whitinsville was forged and repeatedly changed by people who experienced war. In the 20th century, some servicemen returning from the European theater found a lifelong job in “the Works” far less appealing. Living, working, and recreating with a relatively small number of people in a small village was not enough for some veterans of foreign wars, particularly when pay rates did not prove satisfactory. For all their forward-thinking technology, elements of the Whitin family businesses stayed firmly rooted in the past. Those who visited the community saw not just strong ties to tradition, but elements of feudal societies, with wealthy managers and owners living atop hillsides, looking down on the busy Whitin Machine Works.

This close inspection of a handful of residents of one small community in Massachusetts is a reminder that rather ordinary and routine events continue to unfold even during great moments in history. Two generations of industry builders established their lives in the place that came to be known as Whitinsville during successive revolutions. In the 1770s and 1780s, people from Northbridge took up arms and made changes to their ways of life to fight against a great empire. Their desire to be more than subjects of the Crown led ordinary people such as James Fletcher to take drastic, disloyal action.

In the years that followed, their children and grandchildren considered what to do with this new freedom, and worked out how to make the goods that they were no longer forced to consume under the mantle of imperial power. These residents of Northbridge had the power to shape the contours of citizenship for generations of workers. Now, the most visible way that people are remembered for their service to the community is through their service of loss of life in war. Memorials haunt the main village of Whitinsville, a generally quiet place with tenuous ties to industry, but not the thrum of its action.

Visitors to present day Northbridge will find that this first Fletcher family home is one of the few surviving 18th century buildings in town. Unbeknownst to young James and Margaret, one of their daughters would have a huge role in transforming this place from one of quiet farms and workshops to an industrial powerhouse. The children born to Betsy Fletcher Whitin were innovative, shrewd businesspeople. They took their father and grandfather’s ironworks and made an empire all their own. The Whitin Machine Works, which has not been in operation as a textile manufacturer for decades, remains, along with much of the Whitin-funded housing in town.

As we look ahead to commemorating the nation’s 250th year, we have much to learn from the Whitin family, whose early American dream became manifest in a hierarchical company town and global powerhouse of a business. In a place where their ancestors sought freedom from the imperial powers of Britain, generations of this family put down roots and spread their influence far, claiming their vision of success. In the years immediately following the American Revolution, intellectuals debated what would happen in a society where large numbers of free people worked for others, for pay, and lacked their own land to claim.

The debate over the future of manufacturing–and whether such a system might limit personal freedom–was not an abstract one in the Blackstone Valley. In their quest to truly be free from British manufacturing, some veterans established their own curious forms of dominion. Today, many of those old forges and factories are vacant, or repurposed. But the idea that a citizen can and should work for pay, and for the enrichment of others, has proved lasting.

In 1972, Northbridge hosted a huge celebration for their 200th year. Folks drove motorcycles and large parade floats with the number 200; some men even marched in Continental uniforms down the lane for the first time in centuries. But this mood must have been tempered by changes, long-coming, but still stunning, within the town. Around this time, the Whitin Machine works was sold to another corporation, an important break in the dominance in connecting the Whitin name with manufacturing. Then, by the nation’s bicentennial, 1976, the company was shuttered for good. Once again, local people donned colonial garb and sat at spinning wheels to celebrate their independence. By this point such pastimes were for fun. The American Revolution felt distant, indeed. What they did not know was that the age of American industry was also coming to a close.