Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Before the Bomb: Inclusive Archeology in the Cultural Landscape of the Manhattan Project National Historic Site

National Center for Preservation Technology and Training

This presentation, transcript, and video are of the Texas Cultural Landscape Symposium, February 23-26, Waco, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of this presentation on YouTube.

Rachel Adler, Vanishing Treasures Program, National Park Service

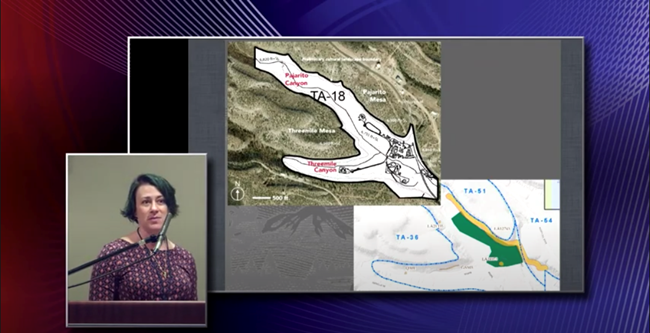

Rachel Adler: So I'm going to talk mostly about being inclusive in the archeology of the cultural landscape for the Manhattan Project National Historical Site. I am just going to start with a brief overview of where it is located. It's located in Los Alamos, New Mexico, which is in Northern New Mexico, about 40 minutes Northwest of Santa Fe. And then the bottom picture is a photo of where Technical Area 18 is within Los Alamos National Laboratory, which I'll refer to as LANL from now on. The Manhattan Project National Historical Park was established in November of 2015. It's managed through a collaborative partnership between the National Park Service and the US Department of Energy, which runs the national labs and incorporates two other sites along with Los Alamos. There are sites in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and in Hanford, Washington. All three of those sites were instrumental in the creation of the atom bomb during World War II. So, I'm also going to be talking a little bit about the challenges that are presented by working together with a federal agency, with a substantially different mission than the National Park Service.

Rachel Adler, Vanishing Treasures Program, National Park Service

The site at TA-18 does retain its historic integrity, and although it currently has a much different use at the moment, it ceased operations as a research facility in 2007, and is now opened primarily as a potential interpretive site as part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Site. Here is an aerial view of the site, which I believe is from 2009, so most of the buildings that you see in the site are no longer standing. A lot of those buildings were removed or demolished in 2009. But what you can see pretty clearly, is that the building clusters and the road systems, they're pretty clearly defined, and a lot of those use patterns are still in place, and so the landscape itself retains integrity. This aerial view, although it focuses on the more modern structures associated with the Manhattan Project, it represents about 1,500 years of continuous human occupation.

So here is a representation of some of the cultural resources that you'll find at TA-18, which again is the technical area of LANL, that mostly represents the Manhattan Project National Historical Site. At the bottom left you'll see what's called a cavate, which is a made-up word, so if you haven't heard of it, that's fine. It's a combination of the word excavate and the word cave. it's an archeological resource that's unique to the area. Because our geology is volcanic, it was created by several large volcanic eruptions, several million years ago. The tough, which is the rock that many of the cliff faces are made of, is very soft and very easy to remove. So, the ancestral Pueblo people who lived in the area, would actually carve dwellings out of the cliff faces, and so what you see there is a pretty good representation of a cavate.

They have numerous features which can include doorways, niches, loom anchors. They'll often have remaining extant earthen plasters and pigments, petroglyphs and intentionally sooted walls and ceilings. Then moving up above that, you have the pond cabin, which is a 1914 log cabin. One of the battleship bunkers on the lower right is from, I believe 1944 is part of the infrastructure of the atomic testing that was done at the site, as is the Slotin building, which was constructed in 1946, although that structure is more representative of the Cold War history on the site.

I want to talk a little bit about the boundaries of the site and of the cultural landscape itself. So, the initial cultural landscape boundary actually did not include many of the prehistoric resources that I was brought in to document and to develop treatments for.

It avoided pretty much all of the prehistoric archaeological sites, because of Julie's [McGilvrey] persistence, that boundary was expanded to what I believe is the picture on the top to include the cliff faces and which is where all the cavates are. And also, some of the mesa top and surface archeological sites. And then recently we actually had a discussion with some of the LANL archeologists to expand the boundary yet again. And so, on the bottom what you can see, the blue dash lines are the boundaries of the technical areas. The green area is actually the boundary of the national park site, and then the yellows areas are documented archeological sites.

And so, we're expanding the cultural landscape boundary to include across a road, which serves as a boundary for the park site, into an area that's not actually part of the national park boundary. And as you can see from that map, the cultural landscape boundary itself is actually much larger than the national park area. So already decisions are being made to include more in the landscape than is actually defined in the enabling legislation for the park. Just because those boundaries do tend to be pretty arbitrary. And I think any of us in this room, whether you're an archeologist or not, knows that boundaries that we draw today have no bearing on the actual use of the landscape through its multiple iterations. As I said, over the past 12 to 1600 years.

Just another note on that, is that with the expansion of the boundary, we've also expanded the period of significance of this landscape to include going back to about, I think we decided like 980. Although there is evidence for archaic occupation of this site, which is going back well into BC. So with the expansion of the physical boundary, we also have expanded the temporal boundary of the landscape, to include all of the occupation and how it's affected the landscape. So this is just a photo to give you a little bit of context. You have the Slotin building in the foreground. And then in the background is one of the cliff faces. That includes all of these cavates that I've been talking about. So you can see it's impossible to interpret the Manhattan Project resources without the context of the prehistoric resources that they exist within.

It's important to note that the remoteness of the site is one of the reasons it exists where it does, both for safety reasons, because they were doing work that involved incredibly radioactive material, and for secrecy, this is very hidden by canyons and by mesas. And so, the existence of the Manhattan Project resources is because of that topography, and the existence of the prehistoric resources, and the cavates is also there because of the topography. The cliff faces and the mesas provided an area for these prehistoric people to build their homes, and to farm and to live. And so those two uses have very little to do with each other, but the geology and the topography of the site, has a huge bearing on why these resources are there today.

And then again, just another example of … this, what you see on the right, is the interior of what we believe used to be a cavate. As you can see, there is nothing about that structure that says this is a prehistoric dwelling. So this was a vault that was constructed in 1948 to house radioactive material. I think the walls are like 18 inches thick of concrete. The floor is 12 inches thick. We believe that this started out as a cavate, like the one that I showed in one of my initial slides, and that it was already partially carved out of the cliff face. So the people working at the site finished the job off. They scraped out more of the material and created a vault. So this exists because of the prehistoric resource that was there before it. And that connection is really important to call out in the cultural landscape, again because it's impossible to look at the resources that exist now, without looking at the context of what was there before and how they relate to one another.

And then so, this is the process of documentation that we're going through for all of the cavates at TA-18. And just to give you an idea, there are two main sites of cavates, because there are two canyons that we're looking at. The smaller canyon has about 29 cavates that we've documented and Pajarito Canyon, which is the larger canyon, includes … at the moment they're around 75 documented cavates, with the inclusion of the cavates across the road and undocumented cavates that are further up the canyon. I'm guessing there are well over 150. And we are documenting every individual cavate with this series of forms that was developed by the Vanishing Treasures Program at Bandelier National Monument, which is a park site that borders LANL. But the archeological resources, as you can imagine are very similar. And so, we are documenting in terms of dimensions, in terms of features, photographs, GPS points, of each individual cavate.

And the idea behind that is to develop treatments, so that if and when the site is open to the public and preservation needs become apparent, or are already becoming apparent, we know how to treat these resources in order to preserve them and stabilize them for the public. We have gotten some push back from LANL as to why we're doing such in depth documentation. As you can imagine, their mission is very different than the National Park Service mission. And because they are administering the land, they're like, "Well, we've recorded that it's there. Why do we need all of this extra information?" And we have the opportunity to do this type of documentation now, and so my feeling is, and Julie's feeling is that we can do it. We might as well collect as much information as we can, while we can, because who knows when this site is open to the public. And because security at LANL is so strong, we don't ever really know what's going to come next. So, we have the opportunity to do it now, and that's what we're going to do.

And so just to end on some final points, I just really wanted to stress the importance of spacial and temporal inclusivity when you're defining cultural landscape boundaries, especially when you're dealing with resources that are not the primary reason for the existence of the park, or the landscape study. So, Manhattan Project obviously exists because people are interested in the history of the Manhattan Project and the structures that were important to the development of the atom bomb, and the history of that scientific development. I think for that reason, it makes it doubly important that you collect as much information when you can on the non-primary resources of these spaces, because they're not the primary focus, and so probably not as much attention is going to be given to preserving them. So, if you're given the opportunity to collect information and to develop preservation strategies for those resources, I think it's really important to do that when you're given the chance. And then my final point is always, you can never have too much documentation, no matter what anybody tells you. There's no such thing.

Rachel Adler, National Park Service

Speaker Biography

Rachel Adler is the architectural conservator with the Vanishing Treasures (VT) Program, based out of the National Park Service Regional Office in Santa Fe, NM. She specializes in the conservation and assessment of archaeological sites, earthen architecture and masonry structures. Recently her focus has been on graffiti mitigation at parks throughout the western United States, helping them to develop culturally and environmentally sensitive strategies for dealing with vandalism at significant sites. Prior holding a position with the regional VT Program, Rachel worked for several years at Bandelier National Monument, working on documentation and conservation of the unique archaeological resources at that park. Rachel has a B.A. in Archaeology from Wesleyan University and an M.S. in Historic Preservation from the University of Pennsylvania.