Last updated: January 29, 2021

Article

Battle of Secessionville - 1862

Library of Congress

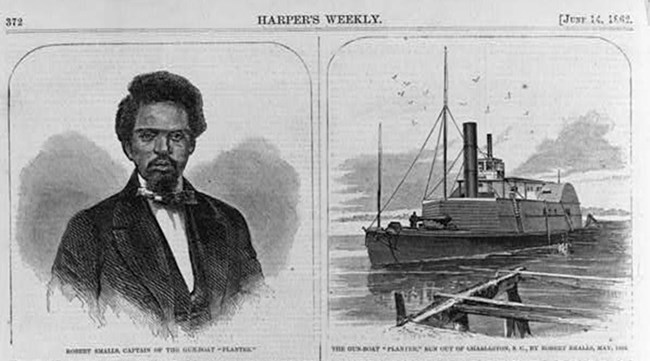

The Bravery of Robert Smalls

A Confederate shallow-draft and armed coastal steamer named the Planter served as a military transport in the Charleston Harbor area. The ship was manned by a white captain, mate, and engineer and five enslaved crewmen. One of the crewmen was a knowledgeable pilot named Robert Smalls. On May 12, 1862, the ship picked up four cannons from Coles Island (part of the Confederate southern flank defenses of Charleston near the Stono River Inlet) and returned to her berth in the harbor where 200 pounds of ammunition were loaded. Leaving the five crewmen aboard and contrary to orders, the white captain and crew then went ashore to spend the night.

Library of Congress

Around 3:00 am the next morning, Smalls and his crew fired the boilers, raised the Confederate and Palmetto flags, blew the whistle to give the appearance of routine, picked up his wife and other women and children located nearby, and steamed toward the harbor entrance. Donning the captain’s straw hat and giving the appropriate signals as Confederate positions were passed (the last being Fort Sumter), Smalls guided the Planter out of the harbor and headed for the Union blockade fleet. Lowering the flags and raising a white bedsheet, Smalls surrendered to the USS Onward.

The Planter was sent with her crew to Port Royal to report directly to Admiral DuPont. The intelligence provided by Smalls included heretofore unknown details of Charleston’s defenses. Of greatest importance was that of the 25,000 troops thought to be defending Charleston, all but a few thousand had been shipped to Virginia and Tennessee. Secondly, the positions and batteries defending the Stono Inlet and southern flank on Coles Island had been abandoned. It was as if General Hunter and Admiral DuPont had been handed the key to Charleston’s back door.

With this intelligence in hand, efforts accelerated to launch the “expedition against Charleston.” The withdrawal of Confederate troops from the string of coastal islands to the south of James Island allowed Union forces to easily overrun them. Confederate Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton’s abandonment of Coles Island gave Union gunboats access to the Stono River and the ability to bring naval guns to bear on the southwestern shores of James Island.

(NPS/Sobol)

Union Army Lands on James Island and the Battle of Secessionville

By early June 1862, some 9,000 Union troops under the command of General Benham had been landed on Coles, Sol Legare, and James Islands along the eastern shore of the Stono River from Stono Inlet as far north as Grimball’s Landing where they enjoyed covering fire from Union gunboats. General Hunter had ordered Benham not to attack Confederate positions on James Island until reinforced or specifically ordered to do so.

The main Confederate defenses were strung across the middle of James Island from Fort Pemberton on the northwest corner of the island to a left flank earthwork position known as Tower Battery. It was located on the narrow 125-yard wide neck of a small peninsula separating James Island from Folly Island to the south. At the northeastern tip of this peninsula lay a cluster of summer homes known as Secessionville. (The name was not related to the secession of states.) The earthwork was manned by about 500 men and seven guns under the command of Colonel Thomas G. Lamar.

During the first two weeks of June, there was sporadic contact between Union and Confederate forces. At 4:30 am on June 16, General Benham sent two divisions to attack the Tower Battery position. Due to the narrowness of the peninsula confined on either side by marshland, the 2nd Division of 3,500 Union troops fell victim to murderous Confederate grape, cannister, and rifle fire as they attacked in three successive waves. Outnumbered, the Confederates managed to hold the position in hand-to-hand fighting until reinforcements arrived and forced the Union troops to retreat. A supporting attack by 3,100 troops of the 1st Division through the marsh from the north also failed. These failed attacks lasted just under an hour. Fearing further casualties, Benham called off the attacks and ordered his men to retreat to the protection of the gunboats on the river. Union casualties totaled 685 killed, wounded, and missing. Confederate losses were 204.

Benham was ordered back to General Hunter’s Hilton Head headquarters and placed under arrest for disobeying orders. After many months, he was cleared of wrongdoing but never again held a field command. The Union troops on James Island were placed under the command of Brigadier General Horatio G. Wright, who had commanded the 1st Division during the attacks. On June 27, Wright was ordered by Hunter to abandon James Island. Colonel Lamar and his men were cited by the Confederate Congress for their “gallant and successful defense of Secessionville against the greatly superior numbers of the enemy.”

This was the only significant overland attack against Charleston during the Civil War. For the Confederacy, therefore, the Battle of Secessionville was a little-known, but decisive victory. Encouraged by the successful reduction of the brick and mortar fortification at Fort Pulaski, attention turned to the strategy of securing Morris Island from which Fort Sumter could be similarly reduced by bombardment, thereby opening Charleston to capture from the sea.