Part of a series of articles titled Great Alarm at the Capital.

Previous: Battle of Cool Spring

Article

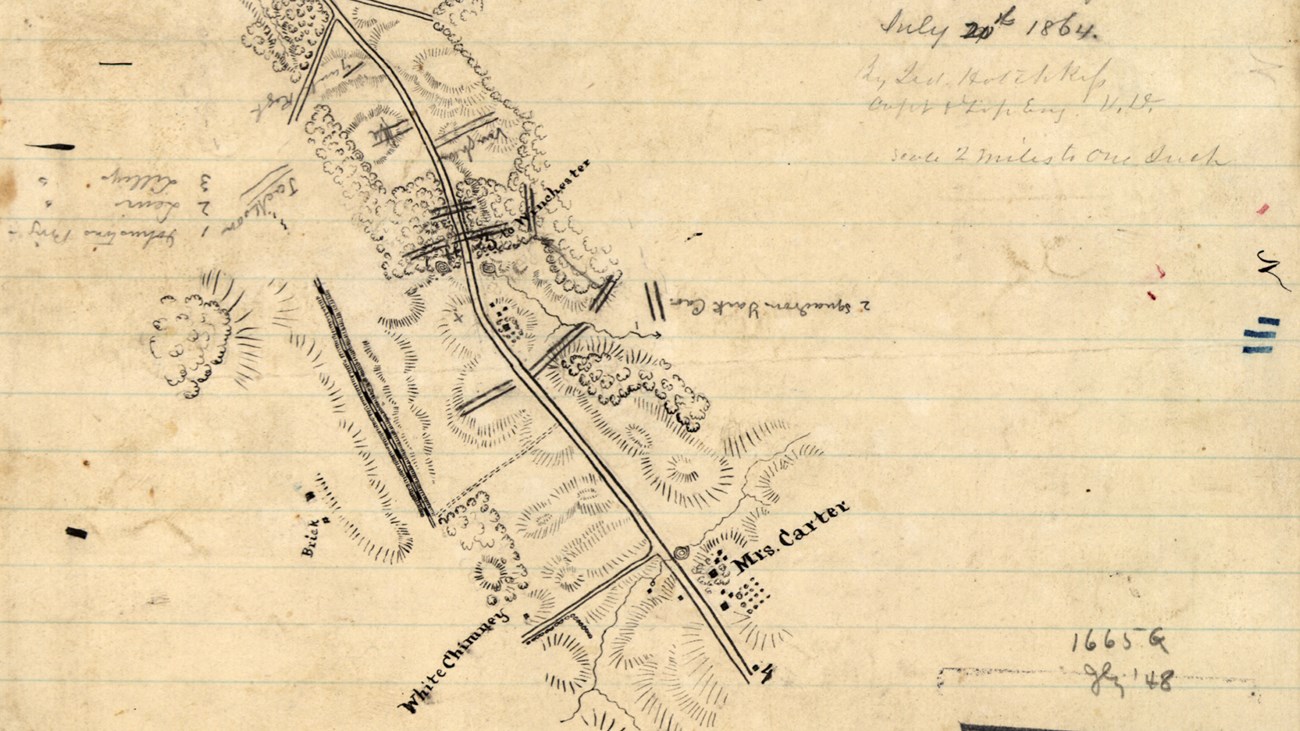

Library of Congress

“… for the first time in my life, I am deeply mortified at the conduct of troops under my command.”

Gen. Stephen D. Ramseur, CSA

Aware that a strong Federal force was advancing towards Winchester from the north and east, Confederate Gen. Jubal Early abandoned Winchester and retreated south. To give him time to evacuate hospitals and stores, Early ordered Gen. Stephen D. Ramseur’s division to occupy the northern defenses of the city. The Federal victory at Rutherford's Farm on July 20, 1864 proved temporary. Four days later, Early struck back with his entire army, at the Second Battle of Kernstown.

Most of Rutherford’s Farm Battlefield is lost to development. Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation (SVBF) maintains a small interpretive area is on the side US Route 11 in Winchester. The battle is also called Stephenson’s Depot, or the Battle of Carter’s Farm, as that farm lay just a short distance north along the Martinsburg Pike. Visit Rutherford’s Farm Battlefield »

Approaching Winchester from the north along the Martinsburg Pike (called Valley Pike south of Winchester) were Col. William Powell’s cavalry brigade, Col. Isaac H. Duval’s infantry brigade, and two batteries of artillery, all under the immediate command of Gen. William W. Averell. Averell’s force totaled no more than 2,600 altogether.

Around 11 a.m. on July 20th, Averell’s command reached Stephenson’s Depot, some ten miles north of Winchester. There they broke ranks to prepare their midday meal. The day was “…intensely hot and the pace the general took exhausted the men,” Jesse Sturm of the 14th West Virginia Infantry recalled, “and many fell out, overcome by the heat.”

Following the midday break, Averell continued his march towards Winchester. Two brigades of Confederate cavalry commanded by Gen. John C. Vaughn and Col. William L. Jackson (second cousin of “Stonewall” Jackson) monitored Averell’s approach, but sometime before 2 p.m. Averell’s force reached John Henry Rutherford’s farm, known as Locust Grove, a few miles north of Winchester.

Vaughn sent back word to Ramseur that a Federal force was closing in on Winchester. Ramseur would later maintain that Vaughn misled him, saying that it was a small Federal force; Vaughn would deny that. Either way, Ramseur ordered his division to leave the northern Winchester defenses and march north to confront Averell. Ramseur, with the two cavalry brigades and several batteries of artillery, would bring about 3,500 men into the field, a larger force than his Yankee opponent. Vaughn had his and Jackson’s brigades dismount, forming them along the edge of a wooded lot on rising ground looking towards Rutherford’s Farm.

As Averell approached Rutherford’s Farm, he posted his cavalry at both ends of Duval’s infantry line, the 2nd and 3rd West Virginia Cavalry on the right, west of the Pike, and the 1st West Virginia Cavalry on the left, east of the Pike. Duval’s brigade straddled the Pike, the 14th West Virginia Infantry holding the right of the line.

When Ramseur appeared with his three brigades of infantry, the Confederate cavalry fell in behind him, but Averell, observing from the roof of the Carter barn, couldn’t see Ramseur’s advance because the woods blocked the view. All he could see was a Confederate skirmish line, so he ordered Duval to move forward. “I see no reason why we may not take supper in Winchester,” Duval replied.

Ramseur’s division continued to advance, but at an angle, his left-hand brigade, North Carolinians commanded by Gen. William G. Lewis, invitingly dangling its left flank in the air.

Duval pressed ahead, and as one member of the 9th West Virginia Infantry remembered, “…all of a sudden, the enemy arose in two long lines of battle from behind the timber, tall grass and weeds, and poured into our ranks a most galling and deadly fire.” With that the 9th West Virginia’s attack was stopped cold. But that was not the case on the far right of the Federal line.

There, the 2nd and 3rd West Virginia Cavalry swirled in around the Confederate left flank, forcing the Southerners back, setting the stage for the 14th West Virginia Infantry. “Yelling like demons,” the 14th smashed into the left flank of Lewis’s 57th North Carolina, delivering a nearly point-blank fire into the faces of the startled Tarheels. The 57th’s line shattered, then completely gave way, thereby exposing the left flank of the next regiment in the brigade line, the 54th North Carolina. The 54th broke, too, and with the West Virginia cavalry pressing the issue, and Duval urging the rest of his brigade forward, the entire Confederate line began to crumble.

Behind Lewis’s North Carolinians was Gen. Robert D. Lilley’s Virginia brigade. They tried to hold up Duval’s men, but with North Carolina troops retreating through their ranks, it became impossible for Lilley’s men to maintain their battle line. Trying to rally his brigade, Lilley was shot – he would be captured and have his right arm amputated – and soon Lilley’s men were retreating south. “We stood our ground a while but so many ran through us that our line was broken up and we took off after the tarheels,” one member of the 52nd Virginia wrote later. “I met Ramseur and he was crying.” Ramseur was indeed upset, and would recall later that, “for the first time in my life, I am deeply mortified at the conduct of troops under my command.”

Gen. Vaughn was able to blunt a Federal pursuit, and by late afternoon the battle was over. In Winchester one town resident, Mrs. Hugh Lee, sitting on her front porch, saw “the distressing scene,” and was told by one Confederate soldier that “we had been whipped, that some of the men had behaved badly, and that [Ramseur] had blundered badly.” Early met Ramseur’s men in Winchester and was not happy. “What the hell did you let the Yankees run you for this evening?”” he asked.

The Federal infantry lost 36 killed, 185 wounded, and six missing, for a total of 237, the cavalry adding perhaps several dozen more to their casualty list. The Confederates suffered about 200 killed and wounded, with some 250 captured. Averell would report later,

“Advancing my cavalry and artillery, I pressed the pursuit, but soon found that I could not venture with the force at my command to inflict further injury upon the enemy without running an imminent risk of losing all we had gained. I therefore maintained my position until dark…”

To Col. Duval, Averell gave all the credit: “Colonel, this is your fight; I have never seen such heroism and bravery displayed, and I could embrace every man in your command.” Duval’s attack, Averell continued, was “the most gallant charge and complete victory over vastly superior numbers.”

The Federal victory proved temporary, for four days later, on July 24, 1864, Early struck back, this time with his entire army, at the Second Battle of Kernstown. And this time it was the Federals’ turn to run.

Part of a series of articles titled Great Alarm at the Capital.

Previous: Battle of Cool Spring

Last updated: January 30, 2023