Last updated: July 24, 2020

Article

Battle of Belmont

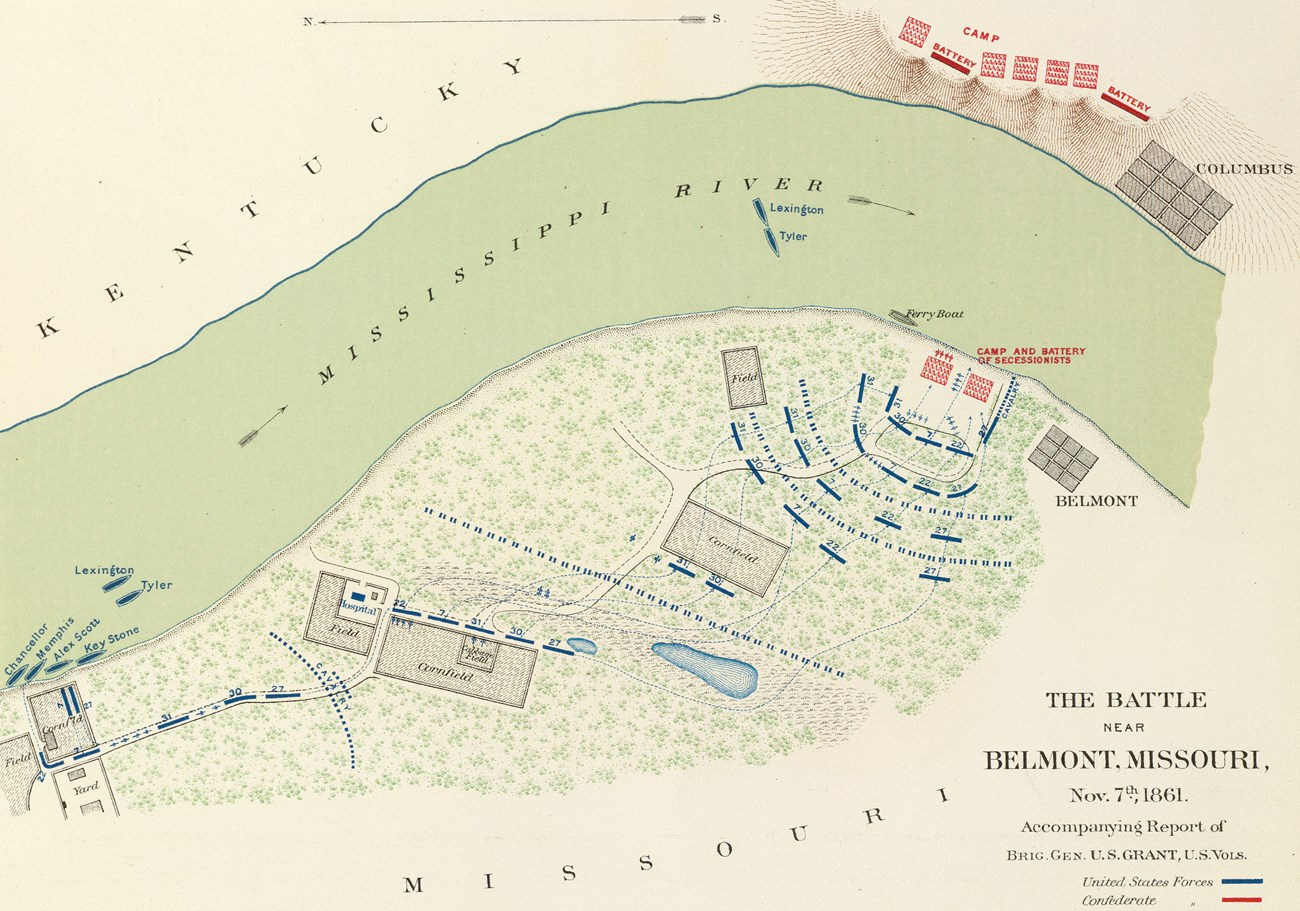

On August 28, 1861 Union General John C. Fremont placed Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant in charge of southeastern Missouri. Soon after taking command, Confederate General Leonidas Polk invaded Kentucky (which had proclaimed neutrality at the beginning of the Civil War) by taking the town of Columbus on the Mississippi River in early September 1861. Grant countered Polk’s move by occupying Paducah, Kentucky, giving Unionists control of the mouth of the Tennessee River. Grant sent gunboats to Columbus to test the Confederate earthworks lying above the Mississippi. The Confederate positions were too formidable to attack from the river, however. Some Confederates moved across the Mississippi to Belmont, Missouri, directly across the river from Columbus. The Confederates wanted to be able to control the river by stringing a chain all the way across to keep Union ships from moving southward down the river.

Belmont, Missouri was a small steamboat landing at the time of the Civil War. The Confederates position on the western side of the river gave them control of communications between southeast Missouri and Confederates east of the Mississippi. General Grant received permission from General Fremont to move towards Belmont, but Fremont did not want Grant to attack immediately. Fremont was hoping to keep the Confederates from moving troops further into Missouri and Arkansas. Grant deployed his troops from Cairo, Illinois on transport ships on the morning of November 6, 1861 with the hopes of containing the Confederates in Columbus and Belmont.

As the transports headed down the Ohio River into the Mississippi, Grant received intelligence that the Confederates were sending troops to attack Unionists in southeastern Missouri. Grant quickly diverted his transports towards Belmont, Missouri, and deployed his soldiers three miles north of the Confederate camp at Belmont on the morning of November 7, 1861. The Unionists marched over rough terrain through forests and cornfields before meeting Confederate General Gideon Pillow’s soldiers late in the morning. Grant’s soldiers drove the Confederates back to their camp at Belmont, essentially trapping the Confederates against the river. It looked like Grant’s soldiers had achieved a complete victory, so they began looting the conquered camp. The Confederates were not ready to stop fighting, however.

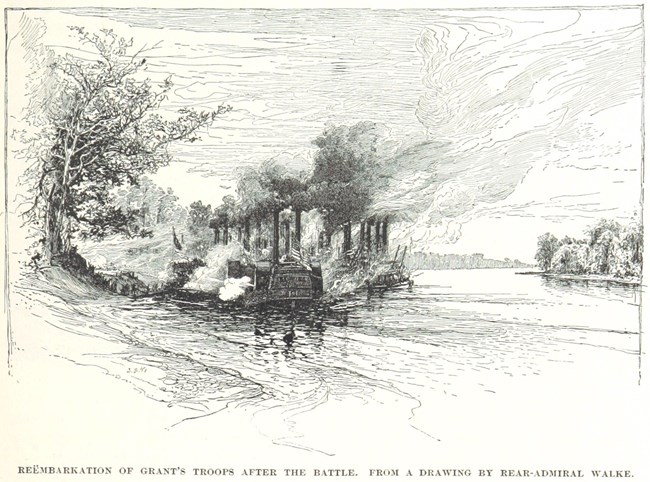

General Polk began sending reinforcements across the river, and he ordered his artillery to fire across the river onto the Unionists in Belmont. The Confederates landed their reinforcements north of Belmont and moved over the terrain that Grant’s soldiers had marched through that morning. Once Grant realized that the Confederates were coming across the river in large numbers, he decided that a retreat towards the transport ships was necessary. Grant’s troops barely escaped as Confederates hounded them all the way back to their ships. Grant was the last soldier to climb into the transport ships. He made his way to his quarters to lay down to rest, believing the day’s fighting was over. But Grant soon heard Confederate shooting coming from the shore as his troops tried to head back to Cairo. Grant went on deck to observe the firefight. As he reached the main deck, Union gunboats drove the Confederates back, and Grant’s army successfully escaped. When Grant returned to his quarters on the ship, he found a hole through the wall of the ship, and a hole through the couch he had been lying on earlier. If Grant had not gotten up to see the firefight, he may well have been killed. The Civil War could have ended much differently.

Even though Grant’s attempt to attack Belmont nearly ended in disaster, he was able to catch the attention of President Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln admired any general who was willing to go on the offensive and take the fight directly to the enemy. Lincoln had been having a great deal of trouble getting his generals to fight, so Grant seemed like the type of general he was looking for during the war. In the spring of 1864, Lincoln placed Grant in command of all Union armies, and Grant would lead the U.S. Army to victory a year later.