Last updated: August 25, 2021

Article

Barbara Allen Gard Oral History Interview

NPS

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW

WITH

BARBARA ALLEN GARD

AUGUST 27, 1991INDEPENDENCE, MISSOURI

INTERVIEWED BY JIM WILLIAMS

ORAL HISTORY #1991-27

This transcript corresponds to audiotapes DAV-AR #4401-4404

HARRY S TRUMAN NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

EDITORIAL NOTICE

This is a transcript of a tape-recorded interview conducted for Harry S Truman National Historic Site. After a draft of this transcript was made, the park provided a copy to the interviewee and requested that he or she return the transcript with any corrections or modifications that he or she wished to be included in the final transcript. The interviewer, or in some cases another qualified staff member, also reviewed the draft and compared it to the tape recordings. The corrections and other changes suggested by the interviewee and interviewer have been incorporated into this final transcript. The transcript follows as closely as possible the recorded interview, including the usual starts, stops, and other rough spots in typical conversation. The reader should remember that this is essentially a transcript of the spoken, rather than the written, word. Stylistic matters, such as punctuation and capitalization, follow the Chicago Manual of Style, 14th edition. The transcript includes bracketed notices at the end of one tape and the beginning of the next so that, if desired, the reader can find a section of tape more easily by using this transcript.Barbara Allen Gard and Jim Williams reviewed the draft of this transcript. Their corrections were incorporated into this final transcript by Perky Beisel in summer 2000. A grant from Eastern National Park and Monument Association funded the transcription and final editing of this interview.

RESTRICTION

Researchers may read, quote from, cite, and photocopy this transcript without permission for purposes of research only. Publication is prohibited, however, without permission from the Superintendent, Harry S Truman National Historic Site.iv

ABSTRACT

Barbara Allen Gard was born and raised in Independence as a next-door neighbor of the Truman family. Along with her three sisters, Gard was a childhood friend of Margaret Truman. The Allen sisters were also a part of the neighborhood group ―Hen House Hicks.‖ Gard explains the mentality of the native Independence residents as they adjusted to having a president of the United States living within their midst, and the impact of a next-door neighbor becoming president. Gard‘s interview provides the reader with a glimpses of a child‘s life in the 1930s and a good understanding of Independence during the 1940s and 1950s, as well as some of the changes since then.Persons mentioned: Harry S Truman, Harry Allen, John Curry, Marie Allen Blank, Harriet Allen Kellogg, Mona Allen, Margaret Truman Daniel, Garrison Keillor, Leola Estes, Bess W. Truman, Betty Ogden Flora, Sue Ogden Bailey, Elizabeth Reese, Virginia Bush, George Grayer, Jane Barridge, Helen Robertson, Ruth Mary Cogswell, Elizabeth Bush, Ted Blank, Ike Berry, Joab Powell, Mary Sue Luff, Madge Gates Wallace, Boris Karloff, Nelson Eddy, Lawrence Melchior, Jeannette McDonald, David Frederick Wallace, Jr., Marian Wallace Brasher, George Porterfield Wallace, May Wallace, Natalie Ott Wallace, Frank Gates Wallace, D. Frederick Wallace, Christine Meyers Wallace, Annie Powell, Benedict K. Zobrist, Mike Westwood, Mary Shaw Branton, Dorsy Lou Warr, Vietta Garr, Ann Smith, John Southern, Robert Weatherford.

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH

BARBARA ALLEN GARD

HSTR INTERVIEW #1991-27JIM WILLIAMS: This is an oral history interview with Barbara Allen Gard.

CONNIE ODOM-SOPER: [Points out that the main recorder is not yet running; secondary recorder picks up preliminary conversation.]

BARBARA GARD: Have you talked to Margaret?

WILLIAMS: Margaret?

GARD: Truman.

WILLIAMS: I haven‘t. We interviewed her way back in ‘83.

ODOM-SOPER: [Unintelligible.]

GARD: Well that‘s one of the things Harriet will know, too.

WILLIAMS: It wasn‘t so much about the growing up here. She talked about so

much of that in her books that I think people are hesitant to talk to

her.

GARD: I had mentioned something to John Curry yesterday something that just flabbergasted him that I assumed everybody had known, but I remembered then Senator Truman coming over to talk to Daddy right after he got back from the national convention where he was nominated for vice-president [main recorder switched on] sitting at the dining room table talking to Daddy. They were having their branch water and bourbon—and he said to Daddy, ―You know, this is the end of my career, Harry.‖—you know my dad‘s name was Harry, too—―This is the end of my career. This is political

2

oblivion.‖ I mean, he was really down. Of course, the ironclad rule in this household was: if you heard a word you didn‘t know, it was obligatory that you go look it up. So, after Senator Truman left, I asked Daddy how you spelled oblivion, so I could go look it up. And it just really made it firm in my mind. John Curry was saying that nobody really seemed to know how Truman had personally felt about it. Well, he came through the back fence to sit here at the table and talk to Daddy about it, you know. He was bummed. Oblivion is a rather strong word.

WILLIAMS: So that was after he was nominated?

GARD: Right, after he came back from the convention, the Democratic

convention, nominated as vice president.

WILLIAMS: Well, I need to give a little introduction here. This is an oral history interview with Barbara Allen Gard. We‘re in Independence, Missouri, on the afternoon of August 27, 1991. The interviewer is Jim Williams from the National Park Service, and Connie Odom-Soper from the National Park Service is running the recording equipment. We‘re in the Allen family house on Maple Street, Avenue.

Well, I‘d like to begin . . . As you know, we interviewed your mother this summer, so I know the answers to some of these questions, but I‘d like to get your version of the story, too. Could you tell me when you were born?

GARD: In 1932, August 22.

WILLIAMS: Was it here in Independence?

3

GARD: Menorah Hospital in Kansas City, but the folks obviously lived here.

WILLIAMS: Is this the only house that you remember living in?

GARD: Absolutely. It is the only house that I lived in here.

WILLIAMS: And you had sisters, right?

GARD: I had three older sisters.

WILLIAMS: So you were the youngest.

GARD: By a mile. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: No brothers?

GARD: No brothers; four girls.

WILLIAMS: Could you run down the names of your sisters and how much older they were?

GARD: Oldest sister was Marie, and she was twelve years older. Next sister is still living. That‘s Harriet. She‘s ten years older. Next sister was Mona Jean, and she was six years older.

WILLIAMS: What are your earliest recollections of living here on the corner of Delaware and Maple?

GARD: I suppose my recollections are the lifestyle: just the big family, the neighborhood gang of girls, the two Ogden girls next door, and Margaret of course, and various others that floated in and out at different times. Sort of a formality to living. You had to put on a dress and your Mary Jane shoes for dinner every night. [chuckling] Lots of good food, you know, fresh corn on the cob and sliced tomatoes—a la Garrison Keillor kinds of descriptions—and of course, how pretty the neighborhood was, all the

4

beautiful trees. If you look around now, the biggest difference is the appearance of the neighborhood, because the trees are all gone due to Dutch elm disease. In fact, I remember after President Truman became President Truman, they tried to take aerial photographs of the community, and they couldn‘t get any because the trees were so huge. It looked like a forest; even the great big houses like the Trumans‘ you couldn‘t see from the air. The trees met in an arch on Maple Avenue. It made a tunnel over the entire street. Of course, all those big trees are gone. But the homes, very big, very comfortable, very well maintained, all the houses painted, all the yards mowed. Of course, it was Depression times, but I don‘t think any of us here . . . The adults may have been worried sick, but none of us really seemed to feel it.

WILLIAMS: What did you father do for a living?

GARD: My dad was a physician, a doctor, in the true sense. He truly believed in the art of medicine, knew a lot about humanity and people, and loved them anyway. Very, very kind, very gentle, understanding man, a very bright man, extremely intelligent, very well-read. He had come from hard times, put himself through medical school completely, but a very good man. He loved his family, was so proud of his four girls, and enjoyed providing for us. He worked very hard. But he was very highly thought of in the community. Of course, I grew up with . . . the minute anybody heard my name Allen, why, it was, ―You‘re Dr. Allen‘s daughter.‖ So I always recognized that there was a great deal of pride associated with that, but a

5

great deal of responsibility, too.

Of course, I went with my daddy. From the time I can remember, I would go in the car with him to make house calls all over this part of Missouri. So he made house calls. I think he charged a dollar [chuckling] for a house call and fifty cents for an office call, you know.

WILLIAMS: Well, I‘ve been told that he actually enjoyed house calls.

GARD: Oh, very much. He loved people. He truly loved people. He loved medicine. And of course, lots of times he‘d come out with tomatoes or corn or whatever, and of course, knew generations: would deliver one child and then deliver the next generation. It was interesting, somebody was telling me yesterday at the Truman Library when I was down there that a relative a couple of generations back of theirs had been an unmarried mother. Of course, in those times that was a terrible, terrible thing, and that Daddy was the only physician that would provide care for her, and how loving and kind and understanding and nonjudgmental he was. I feel like that was a classic story of Daddy.

WILLIAMS: Where was his office?

GARD: When I first remember his office, it was over the Yantis Fritz Drugstore, and you climbed up this little narrow steps to get up to that office. I can‘t imagine what it must have been like for asthmatics or heart patients. [chuckling] It must have been quite a trial. And then he went very fancy and moved into the First National Bank Building where there was an elevator. I even worked in that office for him when he was there.

6

WILLIAMS: Are both of those down on the square?

GARD: Yes, right. They‘re on the corner of . . . let‘s see, it would be Lexington and . . . I don‘t even remember the cross street now, but I certainly know where it is. Right across from the Chrisman Sawyer Bank.

WILLIAMS: That would be Liberty?

GARD: Probably.

WILLIAMS: On the west side of the square?

GARD: Right.

WILLIAMS: To the south.

GARD: Right, the southwest corner.

WILLIAMS: You worked in his office?

GARD: Right, I started working in his office when I was about ten years old, rolling bandages. You know, you‘d reuse the bandages and put them in the old autoclave, and go up and work in his office. And my intention—there are many, many, many doctors and dentists in my dad‘s family—and of course I certainly intended to be one of them. I never thought about ever being anything else other than a doctor.

WILLIAMS: Did your sisters work at the office?

GARD: I think everybody did. I think everybody did. In fact, I think Marie and Monie both, when they came back after graduating from the university, I think they both worked for him on a permanent year-round basis for a while.

WILLIAMS: As you were growing up, was that just something to do for fun, or did he

7

really need the help?

GARD: I‘m not sure. We just all did it, so I really don‘t know. Probably both.

WILLIAMS: Did your mother work down there at all?

GARD: No, never. Never.

WILLIAMS: Did she ever have a job outside of the house?

GARD: Oh, no, Mother‘s the typical boarding school southern lady, you know. Magnolia blossom. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: And took care of the house.

GARD: Yes. Yes, well, she always had help, right. Always had help.

WILLIAMS: I think she told us that you had somebody in common with the Trumans who would help around the house.

GARD: That‘s Leola. Of course, beloved Leola. Leola Estes is her name, and I think she worked for Mother and Mrs. Truman jointly for twenty-eight years. After her husband died, she left and went to live with a brother in California. But I believe she worked for both families for twenty-eight years.

WILLIAMS: Do you know the approximate years?

GARD: No, but Mother, of course, will. Right. No, I know she was here when I was married, and I think she came when I was probably a teenager, so probably from mid-forties someplace to sixties, mid-sixties or late sixties.

WILLIAMS: What did she do in this house for your mother?

GARD: Oh, she cleaned, helped with the cooking, washing and the ironing. Starched my clothes so stiff I couldn‘t sit down. [chuckling] Her classic

8

statement that I remember about Leola . . . I was a terrible tomboy, to the embarrassment of my mother and my sisters, and probably the amusement of my father, and was always in the trees and doing all these very unladylike things, and I remember Leola sighing heavily one day and saying to my mother, ―Mrs. Allen, we are never going to make a lady out of Barbie.‖ [laughter] And I think that‘s probably true. Though she seems reasonably satisfied with the product when I see her nowadays, but that was classic. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: So you keep up with her?

GARD: Oh, yes, yes. When she was living in the Los Angeles area, whenever I had a meeting down there, I‘d stay over an extra night so we could go out for dinner and catch up.

WILLIAMS: And she lives in Ohio now, is that right?

GARD: Yes, I think she‘s in Cleveland with her daughter. A darling person. You‘ll love her. I hope you get to talk to her.

WILLIAMS: I‘m the youngest of five children, three sisters and a brother.

GARD: You understand. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: Could you describe what it was like for you as the youngest of four girls?

GARD: Well, here comes my mother and she‘ll say, ―Oh, Barbie, you know that‘s not true,‖ but it is. [interview interrupted]

ALLEN: How are you today?

WILLIAMS: I‘m fine. How are you?

ALLEN: I can‘t find a thing scandalous about those kids.

9

WILLIAMS: Well, darn.

ALLEN: I thought there were some pages in there.

GARD: There is. We‘ll find it for him. We do have a copy of the ―Henhouse Hicks News.‖

ALLEN: Oh, well, maybe you haven‘t seen that picture of them.

WILLIAMS: Their wedding picture?

ALLEN: No, it isn‘t. It looks like it. I don‘t know when it was taken, but it was a . . . Getting used to this hot weather?

ODOM-SOPER: I never have. I‘ve been in Missouri now for a long time.

GARD: Is that the Trumans? Photo of the Trumans?

ODOM-SOPER: In 1919.

GARD: Oh, isn‘t that pretty? That looks like their wedding photo.

ODOM-SOPER: It is their wedding photo.

ALLEN: Yes, it may be. I don‘t know where they were.

GARD: Oh, I see. It‘s a reproduction of it.

ALLEN: [unintelligible].

GARD: Yes, okay. Yes, that‘s an anniversary invitation.

ALLEN: Oh, was it? I‘ve forgotten what it was.

GARD: All right, do you want your question answered about fourth in the family? My sisters were terrible. Of course, I was lots younger and tagged along, and they didn‘t like it. This is one thing I‘ve always appreciated.

ALLEN: Now be careful what you say.

GARD: See, I told you she would object when I saw her coming around the corner.

10

But Marg was always good about defending me—I always appreciated that—and would stick up for me. They‘d try to get me to go home. But it must have been a terrible nuisance. Think how much younger I was, six years younger than the youngest of the three older girls, and I must have been a terrible nuisance.

WILLIAMS: Well, you didn‘t want to be left out from all that fun.

GARD: Of course not. Of course not. Whatever they did I thought I should do. Of course, they had this baby tagging along with them, two, three years old, and trying to do all these grownup things, so it probably was a real pain.

ALLEN: Oh, I don‘t think it was that bad. They put up with her. They put up with her anyway.

WILLIAMS: What did you all do for fun growing up?

GARD: Well, they were extremely imaginative. And as I say, I‘ve contemplated this after watching my own children grow up without television and how imaginative my kids were, and now watching a third generation glued to the television set. But they did wonderful, wonderful things. The tent made out of the old slide, and doing all kinds of imaginative things with that tent. Or the play that they did, where everybody had a part. Betty Ogden wrote the play from scratch. Everybody had a part and a costume. Of course, all these wonderful attics and basements full of glorious things, you could come up with practically any costume in the world, and very imaginative. Put blankets and quilts over the clotheslines in the back to make the stage and the backdrops, very imaginative. They had, of course, the old chicken

11

house on the back of this property that they used as a clubhouse, until Daddy got extremely concerned about histoplasmosis and tore it down. [chuckling] We probably all have it from playing back there. But the newsletter that they printed, and they would really act like real reporters and collect all the news from the neighborhood and then put together this newsletter that they actually passed out. A very imaginative group of youngsters, and not the kind of thing that I think most kids take the time to do nowadays. Nobody ever seemed bored. I don‘t remember anybody ever sitting around thinking, ―Oh, my goodness, we don‘t have anything to do.‖ It was pretty fun.

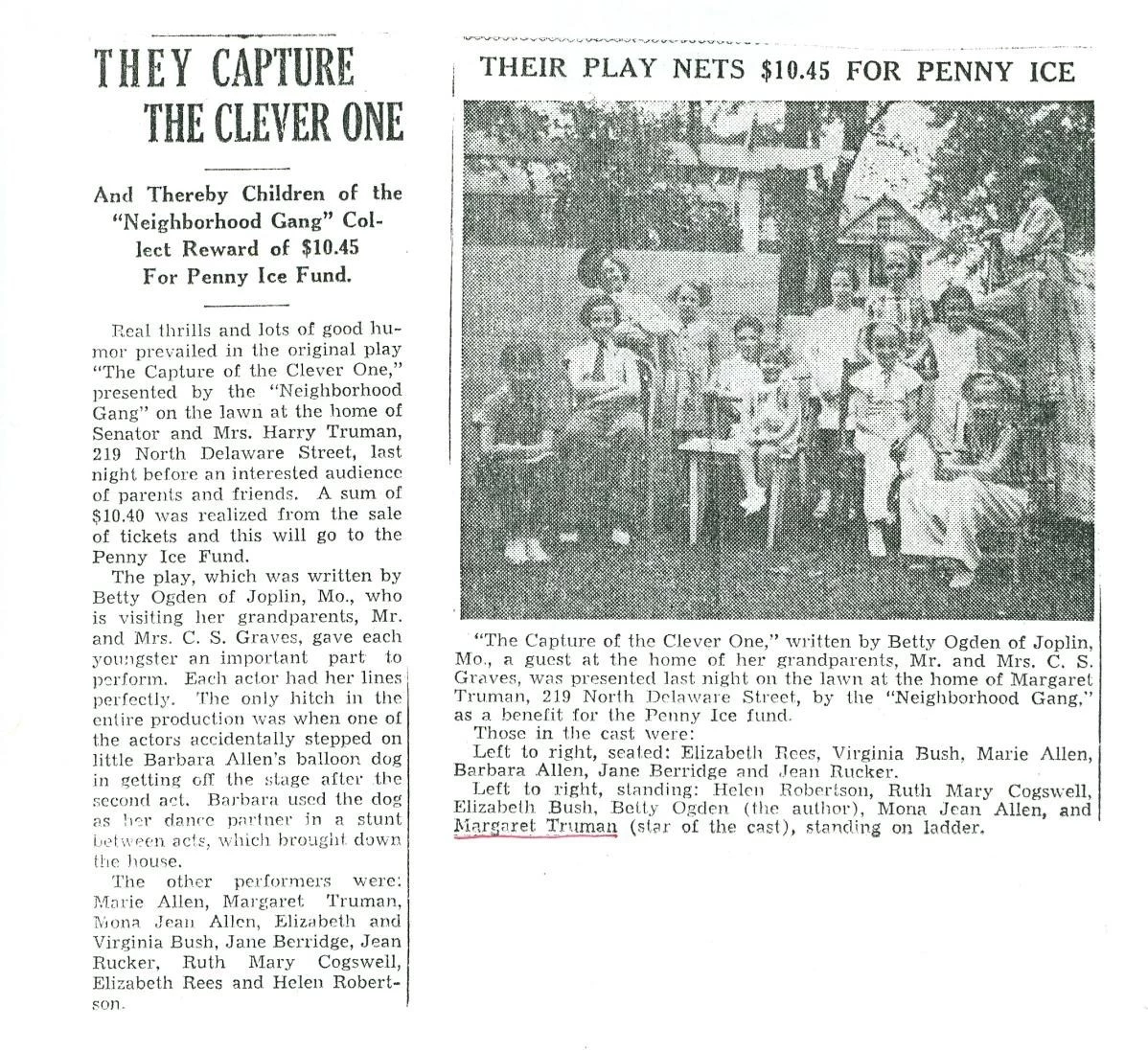

WILLIAMS: We had this article about ―Capturing the Clever One,‖ that play [see appendix, item 1].

GARD: Oh, that was one of the plays, right.

WILLIAMS: About what year would that have been?

GARD: Well, I look what, about four years old? So probably ‘36, maybe ‘35. Is that a four-year-old or a three-year old in the front row there?

WILLIAMS: In the mid-thirties.

GARD: Yes, definitely.

WILLIAMS: Did this go on . . . How long did this . . . they were called the Henhouse Hicks?

GARD: Right, right.

WILLIAMS: How long did this last?

GARD: Well, you see, the house next door burned . . . The house that my dad

12

owned right next to us now burned when I was in kindergarten, so that must have been 1937, thereabouts, and of course that‘s where the Ogden girls lived, so that broke up the gang. And of course Marg moving to Washington. So that was half of the neighborhood right there. And the Ogden girls leaving changed the nature of the neighborhood.

WILLIAMS: Did they live there permanently or did they visit, the Ogdens?

GARD: I assume they were there permanently. That‘s a question, once again, Mother or Harriet could answer for you.

WILLIAMS: I think she said, or someone else said, that they visited their grandparents and lived there part of the year.

GARD: Well, that‘s true. It was the Graves that rented the apartment, and so it must have been; because their mother Virginia, of course, was the Graves‘s daughter. So that must be the case.

WILLIAMS: But as far as you remember, they were there all the time?

GARD: They were just all around. Of course, in the summertime is probably when they were here, and that‘s when everybody was out doing things. If you‘ve spent a winter here, which you certainly have [chuckling], you know that nobody‘s out particularly, so I wouldn‘t have noticed the fact they weren‘t here so much.

WILLIAMS: Could you describe Betty Ogden, what you recall about her?

GARD: Imaginative, really bright. When I stop and think about all these kids, quote, ―the girls in the neighborhood,‖ we‘re talking some really bright, imaginative people. And Betty, very nice, funny, very bright, the brains of

13

the mob in lots of ways.

WILLIAMS: And she had a sister named Sue?

GARD: Sue, and of course she was quite a bit younger and really funny. She and my sister Monie were really funny together. What is the age difference between Betty and Sue?

WILLIAMS: I don‘t know.

GARD: I think it‘s about four years.

WILLIAMS: Betty was about Marie‘s age?

GARD: Yes, or a little bit older than Marie, I think. So that would have put Sue—if that‘s right, and Harriet once again will know that—but that would have put Sue right between Harriet and Monie.

WILLIAMS: I‘ll just go through the list of the people in this picture and see what you remember.

GARD: Okay.

WILLIAMS: Elizabeth Reese?

GARD: That‘s a name that‘s vaguely familiar, but it doesn‘t . . . It‘s not somebody I knew or . . .

WILLIAMS: Virginia Bush.

GARD: Well, she lived right down the street, the second house from the corner down the street. One of the neighborhood gang.

WILLIAMS: Would you see them as much as you would the Ogdens?

GARD: No, no, it would be the Ogdens, my three sisters, and Margaret that were the constant core of the bunch. As I say, others floated in and out at various

14

times.

WILLIAMS: Then there‘s Marie Allen.

GARD: Well, that‘s my big sister, of course.

WILLIAMS: Can you describe her?

GARD: A neat lady. A neat lady. Of course, she died two years ago. Knew everybody and everything. Knew everybody in this town and their cousins. Of course, she rode with Daddy making house calls from the time she was tiny, so she was a real pro at it by the time I was even born, and then of course worked in his office. So she really did, she knew everybody in the whole area. A pretty serious person. Marie was always responsible and, you know, typical Boy Scout oath: loyal, trusting, courageous, kind, all of that. But very responsible, inclined to be serious; where Betty Ogden, for instance, was real imaginative and Marie was the solid one. Very bright. Very bright, very people-oriented.

WILLIAMS: What did she end up doing later in life?

GARD: She married her high school sweetheart, George Grayer, who was an engineer, mining engineer. He became international sales manager for Bucyrus Erie in Milwaukee.

WILLIAMS: Bucyrus Erie?

GARD: Bucyrus Erie. Huge, huge, mining equipment, drag lines, dredges. In fact, he was in the first trade group that went into China when Nixon opened China.

WILLIAMS: Do you know how that‘s spelled?

15

GARD: B-U-C-Y-R-U-S E-I-R-E [sic], I believe.

WILLIAMS: Thanks.

GARD: Terrible colors, maroon and cream on all their equipment. But you see huge, huge equipment by the side of the road that‘s maroon and cream, it‘s Bucyrus Erie. So she traveled extensively with George: Australia, South Africa, England, Italy. She went to China with him. In fact, he died from a virus he picked up on their last trip to China. As I say, she was very, very bright. Of course, that made her interested in a lot of things. She had a great deal to do with the Milwaukee Museum and the Native American section, was a docent there for years and honored by the museum. Of course, a lot of that interest in history, I think, came from the background here in Independence: historical town and all that interest in preservation.

WILLIAMS: And then there‘s you, and then there‘s Jane Barridge.

GARD: I don‘t remember Jane particularly at all. Dark-haired, round face, is that right? Okay. I don‘t remember anything. You know, I remember her vaguely and that‘s about it.

WILLIAMS: Do you know where she lived?

GARD: No, I don‘t. Once again, Mother and Harriet can answer that.

WILLIAMS: Jean Rucker?

GARD: Oh, of course. Of course. The Ruckers were very close friends of my parents. Frank Rucker was editor of the Examiner for years and years and years. His wife Esther, one of my mother‘s closest friends. Jean, their only child, pretty, pretty blonde girl, a very nice girl. She was my sister Monie‘s

16

age and just a really fun, nice girl. They lived down Delaware and Waldo Street, the house right behind the Sawyer-Jennings House.

WILLIAMS: Then Helen Robertson.

GARD: Oh, that must be . . . Good heavens, I didn‘t realize she was in that play. [chuckling] I believe that‘s Mrs. Robertson, who was all of ours first-grade teacher. Wonderful, wonderful teacher, and that was her only daughter. Mrs. Robertson was very involved in drama, taught drama and elocution, and was the production manager for a number of Shakespeare plays that we all participated in later. So I believe that‘s probably who that is.

WILLIAMS: Ruth Mary Cogswell.

GARD: Right. Once again, her mother was a very close friend of my mother. She was my sister Monie‘s age. Funny, funny, really great wit and sense of humor, a really neat girl.

WILLIAMS: Elizabeth Bush.

GARD: All right, once again, the second house from the corner down there, right. And they were around a lot, as I say, because of the proximity, right.

WILLIAMS: They were twins.

GARD: Yes, right. Bush twins, which is a terrible way to identify people instead of by their names, but, right.

WILLIAMS: Mona Jean Allen.

GARD: That‘s my sister Monie, right.

WILLIAMS: Could you describe her?

GARD: Ooh! A big I.Q. Super bright I.Q. She had had spinal meningitis when she

17

was less than two years old, nearly died, lost the vision in an eye and the hearing in an ear. I doubt that anyone ever considered my sister handicapped in any way. A very beautiful girl, if you‘ve seen the photos of her. Dark, dark hair and dark, dark eyes, and funny, just this great sense of humor. A really big I.Q. I think she graduated from a class of 6,000 at MU, and she was salutatorian. The valedictorian was a totally blind war veteran. I thought that was rather interesting. But she was in rather fragile health. She was never an invalid, I don‘t mean to imply that, but she wasn‘t as vigorous as some of the rest of us, but it didn‘t ever seem to stop her much.

WILLIAMS: What did she do later in life?

GARD: She married Ted Blank, who is a developer here in town. He went into business with one of my dad‘s first cousins, Ike Berry. She was active in Junior Service League. She had worked at the high school office. As I say, she graduated from the University of Missouri with a degree in sociology, salutatorian of a huge class. And she died of cancer at forty-four.

WILLIAMS: And Margaret Truman.

GARD: Well, as I say, my protector. I think, because she had no siblings, why, this sibling rivalry, the internecine warfare upset her greatly. Once again, a very, very bright, interesting person. As I say, I stop and think back on all these kids, and I took that for granted that all kids were imaginative and really bright. But when you stop and separate them all out, this was an exceptional group of girls. I guess the first thing I really remember about Marg as a person, other than her kindness to me and just all of us moving

18

in a big pack, was how hard the relocation was for her. This neighborhood was so permanent. I mean, you look at the houses, they‘ve been here forever, the families have been here forever. Mother‘s relative Joab Powell, I think, hit this part of Missouri in 1822. Just a sense of constance, of always being here. The Truman house, of course, was the Gates mansion, which was Mrs. Truman‘s family, and just a sense of constance. And then for her to have to leave. I remember my sisters feeling upset about Marg leaving, and I think it must have been very hard.

Probably one reason I remember it, it was shocking to me to think that anybody ever left. The same way with the house burning down and the Ogden girls not being around as much anymore. Because everything . . . I talk about the size of the trees, the size of the houses, everything was so permanent. And I really don‘t quite know how I could have been that protected. We‘re talking about the Great Depression, we‘re talking about moving into World War II, but up until the beginning of the war, that was the feeling, that everything was just permanent, here forever.

WILLIAMS: So, as far as you were concerned, the Depression really didn‘t mean much?

GARD: No, as I say, the adults may have been worried sick, but all of us, sitting out in the side yard, watching the fireflies and making daisy chains and drinking lemonade, it seemed very permanent, very constant, very secure.

WILLIAMS: Could the Depression have been one of the reasons you would have a play for the Penny Ice Fund, to raise money for that?

GARD: I have no idea, but I would assume so. I would assume so.

19

WILLIAMS: Was it typical to have charities? Do you remember being involved in charities?

GARD: No, see, I‘m three years old in that picture. I don‘t remember.

WILLIAMS: But later on, were you involved in charitable activities?

GARD: Well, of course, when I was, what, I was nine when the war started? Was I ten? I guess I was nine. And once again, I guess this is the small town business, but this business of being involved . . . Remember taking my wagon and going from door to door to collect everybody‘s cooking grease, which was recycled to make ammunition. And doing the same, my red wagon, collecting newspapers. Nowadays you wouldn‘t dare let a nine-year-old girl in pigtails go from door to door. But you did. Everybody was involved in every way. You saved tinfoil, you did everything possible to do. So, in my case, it wasn‘t charity, it was the war effort. But I do remember feeling real heartache at school. My mother has chided me greatly, ―Why didn‘t I come home and tell her and they would have done something about it?‖ It never occurred to me. But seeing children that I know now that are substantial citizens in this town, that lived through it obviously and survived and went on and educated themselves and made wonderful lives, but coming to school in winter with no coats, coming in warmer weather with nothing but strap overalls and no shirts and no shoes, and big families, and knowing how desperate the situation must have been. And I know several times I walked home with those youngsters to play at their houses after school, and then Mother would come pick me up. And

20

stupidity on my part, I simply never realized how desperate the situation must have been. Because we were all friends and there weren‘t any particular barriers. But when I look back on it now and think about the clothing, and the fact, of course, there was a hot lunch program at school, so that there was some provision made. But obviously I think their charitable activities were in response to those things that they were old enough to see and recognize.

WILLIAMS: It says in this newspaper article that [reading] ―The only hitch in the entire production was when one of the actors accidentally stepped on little Barbara Allen‘s balloon dog when getting off of the stage after the second act. Barbara used the dog as her dance partner in a stunt between acts, which brought down the house.‖

GARD: My word! I had no idea I had such talent! [chuckling] Well, you‘re talking to a total klutz here. [laughter]

WILLIAMS: Somebody stepped on your dog and popped it.

GARD: [laughter] I have no idea. I have no particular memory of that one at all. I don‘t think I wore a costume in that one. See, the ones where we had elaborate costumes I remember, but . . . I had no idea I had a dance number.

WILLIAMS: It says Margaret was star of the cast.

GARD: That would make sense. She had a tremendous amount of poise. For a very young person, she was extremely poised, with a lot of presence, so that definitely makes sense.

21

WILLIAMS: Destined for the stage, huh?

GARD: Definitely. Definitely.

[End #4401; Begin 4402]

GARD: . . . party for us every Saturday. We‘d go up there and dance and . . .

WILLIAMS: At Jennings? Every Saturday?

GARD: Yeah, every Saturday night. It was really neat. Had no idea at the time what a deal it was.

WILLIAMS: Why was this play in the back yard at 219?

GARD: I don‘t know, because lots of times they were in the back yard of the house next door, where the Ogden girls were staying, so I don‘t know how we happened to be over there. Once of the problems with their back yard was it sloped, and of course the yard right next door was perfectly flat. So we must have had a larger audience or something. I have no idea. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: But they weren‘t always in the Wallace yard, or the Trumans‘?

GARD: Oh, no. No, no. No, as I say, lots of times they were right next door. And I assume that they never used this lot on the other side of the folks‘ house because it was so exposed, you see. Either the lot on this side was among all the houses, or the Gates house, the back yard was screened from the street. And of course they had a big grape arbor over there, and of course the folks had a big grape arbor here, so they were screened from view.

WILLIAMS: Was that important, to be secluded?

22

GARD: Well, I don‘t know about the rest of them. As a three year-old, making a fool out of myself . . .[chuckling]

WILLIAMS: Dancing with a balloon dog.

GARD: Dancing with a balloon dog, it seems fairly important now, but . . . [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: Where did you get the costumes? Who would make them?

GARD: Oh, attic. Oh, I doubt if anybody ever had to make anything. I really don‘t know. As I say, Harriet could probably tell you this, but think how long everybody‘s lived in all these houses. We could walk upstairs to the attic today and come out of there costumed any way we wanted to. It‘s just amazing. When my youngsters come visit—of course I‘ve had a more nomadic lifestyle and you clean stuff out—but even so, I‘ve saved a lot of things simply because of the fun of having all these marvelous things. So you could go in the Truman attic . . . In fact, Harriet was talking about the Truman attic just last week, about all the wonderful things up there. So you could go in the old trunks and find anything you wanted to.

WILLIAMS: So the neighborhood mothers weren‘t around sewing costumes and things like that?

GARD: Well, I don‘t think my mother knew how to sew. [chuckling] And I don‘t know about Mrs. Truman, but she never impressed me as the kind that would be sewing costumes—and certainly the grandmother over there wouldn‘t have been. So I don‘t know, unless some of the other mothers

23

were seamstresses.

WILLIAMS: I assume in the wintertime these activities would slow down, or at least come indoors?

GARD: Well, I‘m sure so. I‘m sure so.

WILLIAMS: What would you do outside in the wintertime? Anything?

GARD: Oh, snow was wonderful, of course. There was enough snow to make snow forts and all of that, though none of my sisters were outdoor folks at all. None of them were.

WILLIAMS: Just you.

GARD: Right. Right, well, as I told you, I was a tomboy. I was a lot rougher than the rest of them. Well, both my oldest sisters were into horses and riding, and I don‘t know whether the stable at that time had covered facilities or not. But that, of course, you could do up until the gales howled.

Everybody read. Everybody read all the time. I remember being about four or five years old, and my mother‘s cousin worked at the library, which was on the corner in the old junior high school building that burned, and walking up there at the age of five and printing my name to get my library card, and what a big deal it was. So that I rather expect everybody . . . I know all three of my sisters, and I rather expect Marg and everybody else, was under a book.

WILLIAMS: Did you do anything like sledding?

GARD: Oh, sure. Oh, sure.

WILLIAMS: And you mentioned ice skating.

24

GARD: Right, the Swope pond. Everybody ice skated on the Swope pond.

WILLIAMS: Was that down by where the Swope mansion was?

GARD: Yes. Yes, it was behind the mansion. And Farmer Street hill was great for sledding. It was really scary, very steep. And so those things were wonderful. Well, in fact, even the hill by Margaret‘s house on the other side, on what‘s now Truman Road, was then Van Horn, was steep enough for a little bit of sledding. So, yeah, all those things were great. And hot chocolate, of course, when you came back. The great tradition.

WILLIAMS: How often were you in the Gates house?

GARD: A lot, because I was tagging around on everybody‘s heels. Summertime the kids were in the basement a lot. It was very cool. Very scary. Oh! Very scary. And one of the great entertainments was to sit in that spooky, spooky basement—I mean, we are talking big, thick wood doors and lots of little rooms, and stone foundation walls, of course—and to sit in there and close the door—and of course it was black as pitch, there was no outside light—and tell ghost stories. And of course I was teeny-tiny, and they scared me to death. In fact, they all ran off and locked me in there one day, and I‘m surprised I‘m not totally traumatized. [chuckling] But that was great adventure, you see.

WILLIAMS: So you‘d go way back into the back of the basement?

GARD: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. But of course it was very cool down there, too. And there was a constant supply . . . wherever you were, there was a constant supply of lemonade and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. It was just a

25

never-ending supply. So, as I say, the tent—the Army blankets that my mother just asked about sixty years later—they made a tent out in the yard, and I‘m sure the purpose of that was some shade. But it must have been as hot and humid as it is now, but of course we were all out in it. But you had to get cleaned up for dinner. I don‘t care where you‘d been or what you were doing, you had to get a bath and get dressed for dinner.

WILLIAMS: What were your typical play clothes?

GARD: I think I had kind of little romper sun-suit kinds of things, and I don‘t really remember what my sisters were wearing, to tell you the truth. Probably cotton dresses.

WILLIAMS: No jeans?

GARD: No. Oh, my goodness, are you kidding!? [chuckling] Of course not. Oh! Attack of the vapors here. [laughter] No jeans. No, that‘s one of the things that scandalized my sister when I was about six or seven years old, was because I wore jeans, and it, or course, was not the thing to do.

WILLIAMS: Mary Sue [Luff] probably got you into that.

GARD: [laughter] I don‘t think I was hanging around with Mary Sue all the time in those days. I think it was innate. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: What do you recall about the attic in this house or the Gates house?

GARD: Well, our attic is wonderful, big and spooky, two sets of stairs into it, just like there are two sets of stairs here in the house, and full of wonderful things—I mean, incredible things. I was up there last time I was home and discovered some of my grandmother‘s hats, one of them a

26

black felt hat with a whole bird wing on the front of it. [chuckling] I mean, gross, but . . . So the Truman attic was like that, and just full of incredible things. And of course this basement, the big old leather trunks with my dad‘s World War I uniform in it, the newspapers that said: ―War is Declared.‖ ―Germany Surrenders.‖ You saved everything. And of course their house, and this house too, I always . . . when I think of the homes, I think about the libraries. And when I think of Mr. Truman when I was tiny, he was in the chair in the library. My dad, here at his desk in the library, or in his big chair in the library.

WILLIAMS: And here your library is on the west?

GARD: Yes, right, right. But how many homes have libraries anymore? But that was very important, that library. I wondered about it. I was thinking about that yesterday. When Mr. Truman and dad would talk, they‘d be sitting here at the dining room table. I have no idea why they didn‘t go into the library, but they usually sat at the dining room table.

WILLIAMS: Sipping bourbon.

GARD: Well, I think my dad had scotch, I think. [chuckling] No, it probably was bourbon. I don‘t know what Daddy drank. Branch water and something, I‘m sure, but they both had them.

WILLIAMS: Did Margaret have a playroom, or would you play in her room, do you recall, in her house?

GARD: No, I really don‘t. We didn‘t go upstairs in the house very much. We were usually outside, or on the porch, or in the grape arbor, or in the yard

27

over here. I really don‘t remember playing in the house very much. And you have to remember grandmother was around, and I have a feeling she wasn‘t real tolerant of a herd of girls running in the house.

WILLIAMS: Grandmother Wallace?

GARD: Yes.

WILLIAMS: What do you recall about her?

GARD: [Breathes deeply inward] She was very formidable. Very formidable. My whole impression was one of sternness. She would come out on the porch if we were being too noisy or whatever, but she was very, very formidable. And I, of course, was used to southern-type ladies, so she was very formidable.

WILLIAMS: Nice.

GARD: Well, I didn‘t have that much contact with her, but she was usually chastising us for something.

WILLIAMS: Not the sweet, grandmotherly type?

GARD: Not at all. Not at all, no. She was very, very stern, very imposing-looking, and I suppose cross would be a . . .

WILLIAMS: I guess she wanted to keep her house from being destroyed. [chuckling]

GARD: Actually, her response was probably totally reasonable. [chuckling] We‘re talking how many kids? We‘re talking a whole herd of girls, so . . . right. Mother was always extremely mellow about that. That‘s interesting. Because we would go up one stairway and come down the other. And the Graves as well, just totally tolerant—probably tolerant to

28

a fault. But of course the chicken house probably saved everybody‘s sanity because we were all back there.

WILLIAMS: Would you go down to the square very much?

GARD: Well, the square was it. I mean, everything was on the square. If you went to Kansas City, it was a whole day‘s trip, and a big affair. You went to Kansas City shopping for the day, and you had lunch at Wolferman‘s and all that. So the square was everything: all the banks, the dress shops, Bundschu‘s, Knoepkers. Amazing. As I say, I remember walking the block to the library, absolutely by myself, at five years old. And that was fine, you were perfectly safe to do it. I was not to cross the street, though, so I didn‘t go uptown by myself. But yes, the square was a big deal, and the center of the town.

WILLIAMS: Would you go to anything like movies or the soda shops?

GARD: The movie, I‘m sure there was a movie up there. There was the Plaza Theater. And what was the one on the corner? I can‘t even remember the name of it. [Granada] The very nice one was up here on the corner, just two blocks up the street. And then there was the Plaza, and then there was the Electric Theater that was not as nice as the other two. I really don‘t remember going to the movies much at all until I was probably nine or ten.

I remember my mother‘s story about my dad taking the Ogden girls . . . I don‘t know whether Marg was with them or not, but I know it was the Ogden girls and my three older sisters, and my dad took them to

29

see the movie ―The Mummy‖ when it first came out. [laughter] and I guess no one slept in the neighborhood for weeks afterwards. Mrs. Graves chastised my father severely for taking those tiny girls to see this terrifying movie. And of course Mother had no idea what it was all about. But it must have really been something. I‘ve never seen it. I guess they‘ve re-released it. It was Boris Karloff, wasn‘t it? Yeah. So obviously movies were around, because that has been a classic neighborhood story: Dr. Allen taking all these little girls to see a horror movie. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: I heard that Margaret had a thing for Nelson Eddy.

GARD: Oh! Nelson Eddy and Lawrence Melchior. She had huge scrapbooks. But everybody had a thing for Nelson Eddy. You know, Nelson Eddy and Jeannette MacDonald were it, so she was not alone in that. I think the world had a crush on Nelson Eddy. But yes, she absolutely did. And then later Lawrence Melchior.

WILLIAMS: What about the drugstores or the soda shops? Were those down there?

GARD: Oh, I‘m still a chocolate soda addict, and of course it began here in this town. But the big, big soda fountain at Yantis Fritz Drugstore—huge, big soda fountain—and of course it was marble. And of course my dad‘s office was above it for a long time, and it was obligatory to stop and have a chocolate soda. Oh, wonderful!

WILLIAMS: I‘ve heard Margaret liked chocolate sodas, too.

GARD: Oh, how could you not? [chuckling] But they were great. And Cokes.

30

You know, Cokes were real fountain Cokes, absolutely made with the syrup and the carbonated water, and they were wonderful. And cherry phosphates. I have no idea what‘s in a cherry phosphate, but they were absolutely wonderful.

WILLIAMS: Was that something you‘d do like every Friday night or anything, a routine like that?

GARD: I don‘t know. You have to remember I‘m the tagalong, see, the baby tagging along at everybody else‘s heels, so I don‘t know. I‘m sure we had to dress up if we went uptown, though. I‘m sure it was a big deal, even if you were only walking. Yes, yes, I‘m sure, even if you were only walking three blocks up the street, that you had to be dressed up.

WILLIAMS: What does ―dressed up‖ mean in the ‘30s and ‘40s?

GARD: Oh, a dress and fancy socks, and your Mary Jane shoes. [chuckling] and all of that. And of course church was white gloves and hats. I think about my mother and Mrs. Truman and my grandmother. It‘s always the hats and the gloves and . . . .

WILLIAMS: Where did you go to church?

GARD: First Baptist Church. Only my daddy and Mr. Truman didn‘t make it to church very often. [laughter] I doubt if either one of them set foot inside the church for fifty years, but they were both members.

WILLIAMS: How much do you remember David and Marian Wallace?

GARD: Oh, a lot when they were here. Whenever they were here visiting, why that was a big deal for me because they were closer to my age and I

31

really liked them both. And that was fun because the rest of the time I was so much younger than everybody else, and there wasn‘t anybody my age around in the whole neighborhood. And so that was just great when David and Marian were here. Really nice, nice children. I loved playing with them.

WILLIAMS: Would they just mix in then with the neighborhood?

GARD: Well, actually, by that time . . . see, with the age difference—my sister twelve years older, ten years older, Marg eight years older, I guess—they had all gone on to college by the time Marian and David were big enough to float back and forth. So we were kind of on our own, going through the back fence.

WILLIAMS: So it would have been nice for you to have a fresh crowd to replace your sisters who had gone.

GARD: Oh, yeah. [laughter] Wasn‘t anything like it. See, the war came along and life was totally, totally different after 1941.

WILLIAMS: How much contact did you have with Margaret‘s aunts and uncles that lived down . . . George and May, Natalie and Frank?

GARD: Well, I knew them all, of course. My closest friend knew May very closely, and I‘m not certain how—I‘ll have to ask her exactly how—so I visited there a lot with Prudy and so I knew May better than anybody else.

WILLIAMS: What was she like?

GARD: Oh, a wonderful lady. A wonderful lady. And until just the last year

32

she‘s still, like my mother, just in total charge of her affairs. But just a lovely, funny, gracious lady, a neat sense of humor, and really nice. And I remember George, of course, being a very nice person. I knew who Natalie was, but not as well as I knew May. And I remember Fred, of course. Very nice. He was, of course, young in those days, and very nice. Fred and Christine, of course, this very nice young couple.

WILLIAMS: Were they just like any other parents of friends of yours, Fred and Christine?

GARD: Right. And of course when they were here they were visiting parents, so of course they were mostly visiting and I was enjoying having playmates. But I remember them. See, they were so much younger than my parents, for instance, that I was so impressed with how young they were.

WILLIAMS: What was Bess Truman like in those days before she became first lady?

GARD: Well, I don‘t think she changed a lot after she became first lady. And I remember that when they came back here to town she was . . . she just never changed. She was always the same person. But she and my mother were very much alike: very gracious ladies, very, very kind, gracious people. They were taught to do what was expected of them, to always conduct themselves properly, to be thoughtful of other people, to always be the poised ladies. And she was. She was. I always felt she had a streak of fun, maybe a streak of mischief. But it never showed—I mean, she was always just lovely.

I remember a particular incident about her. When I was

33

married—of course I was the youngest of four—and my sisters had all invited the Trumans to their wedding. We all four were married right here in front of this fireplace, and the Trumans had come to all my sister‘s weddings. And when I was ready to be married, he was in the White House. And my mother and I talked about it, what to do. Here were neighbors, friends of the family for years, friends of my father‘s and mother‘s, and what should we do? And finally we decided, well, we shouldn‘t invite them because they would think we were inviting them just because he was in the White House, which was totally stupid, but anyway that was our decision. The morning of my wedding, Mrs. Truman came through the back gate with this lovely, wrapped gift—it‘s a silver bread tray that I cherish to this day—and gave it to my mother, said, ―This is for Barbie,‖ and she was obviously hurt that she had not been invited to the wedding. And of course I look back on it now, here was this wedding going on next door, family friends for years and years and years, and we hadn‘t invited them because we were falling over backwards not to appear to be imposing. And yet it was important for her to come over with this gift for me. And I think that‘s typical of her. She never forgot who she was, she never lost her sense of who she was, of what she came from, never lost that lovely, gracious presence.

And I thought—in fact, I felt—when she was older and living as my mother‘s living now, with most of her friends gone and family far away, as with my mother, that people probably still fell over backwards

34

and were not as friendly and as close and as neighborly as they would have been if she had not been a president‘s wife. And I find that tragic. My mother, for instance, didn‘t go visit the way she should have and would have, and Mrs. Truman didn‘t come out to visit the way she probably would have and should have. And that‘s strange that these people in this town would do that, but I think everybody was trying to so hard to be considerate.

And of course we were all told you don‘t talk about the Trumans, you don‘t talk to the press, you protect their privacy, and I think we‘ve all been very careful to do that. I think the reason we‘re all willing to talk now is because we realize, like with my two sisters gone and third sister in very poor health, my mother ninety-four, if we don‘t do it now, it‘s never going to be done. But everybody was very, very careful.

WILLIAMS: Was she any different than any of your other friends‘ mothers?

GARD: No, not really. Not really. As I say, when I think of Mrs. Truman I think of my mother. No. And I think about how they lived, the three generations in one household, and of course we lived here, three generations in one household. And of course my grandmother was just a wonderful, loving, kind woman that never created any kind of . . . she would have died before she‘d have created any kind of uproar in the household. My father loved her as if she were his own, and I know that was not the case next door. I mean, how could it have been, because the personalities were so different. And public things, of course, that . . .

35

WILLIAMS: With Madge.

GARD: Yes. And she was publicly very critical of him and very inconsiderate, I think, in her public utterances. But that was an assumed way of life, you see, that generations looked after generations. The families all close, the other siblings in the houses behind, and so that was a tradition. And then all of a sudden, here‘s my mother, there was Mrs. Truman, with no family, no family around. And it must be very, very hard, because it‘s a total break from what they‘ve known all their lives. I don‘t know, but I would assume that those last years were rather hard.

WILLIAMS: How long did your grandmother live here?

GARD: My grandmother died in 1963, and I think my grandfather died in the early ‘40s, so she was probably here twenty years.

WILLIAMS: She was different than Madge Wallace?

GARD: Oh, my grandmother, kind, loving . . . Look at the photo. Kind, loving, gracious. A wonderful, wonderful lady.

WILLIAMS: And that‘s your mother‘s mother.

GARD: Yes, right.

WILLIAMS: What was her name?

GARD: Annie Powell.

WILLIAMS: Powell, that‘s right.

GARD: Powell. And see, if you look at the old Grinter map of Independence, Missouri, you see Joab Powell‘s homestead. It think it‘s 1820, 1822.

WILLIAMS: Joab?

36

GARD: Joab Powell. He founded the Six Mile Church, the Salem Baptist Church, the . . . . Sure. Yeah, so like everybody in Daddy‘s family was a doctor, dentist, or nurse, everybody in Mother‘s family was a Baptist minister. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: Okay. That‘s a good mixture.

GARD: I don‘t know. Curious. [chuckling] Theologians on one side, scientists on the other.

WILLIAMS: What was Harry Truman like as a neighbor, a friend‘s father?

GARD: A friend‘s father. You know, most of the dads . . . And when I remember him when I was little, it was like everybody else‘s daddy, you know, always the formal business suit, the straw hat, left in the morning and went to work, and you didn‘t see him until late at night. Very tolerant. As I say all these fathers with this huge gang of girls, this herd of girls, and they were very tolerant. They always seemed rather amused at what everybody was doing. Probably they were very pleased at what everybody was doing, but they always seemed very tolerant, very kind, very amused.

I was so interested when I came back with a university degree from the University of Kansas and was in the first class of docents at the museum. And of course Kansas was extremely hostile to Harry Truman in those days, but as a history student I certainly had the big perspective. And to get to come back in that first class of docents and have him help train us, and then get to hear his perspective on these world-shaking

37

events that had taken place during his presidency was absolutely awesome. I was awed about it at the time. I look back . . . ‘course, I taught political science at California State University in Chico, and of course teaching government and political science and thinking about all the things I heard him say, it was an incredible experience.

One of the things I remember, being very young—about twelve, thirteen—and reading something in the newspaper about the President of the United States being a . . . I believe that word they used was ―cornball,‖ and realizing that the media lied, that this was a man who was very intelligent, was very literate, very well-read, had heard him talk to my father in very intelligent, wonderful, far-reaching conversations. And then to hear the media describe him this way—and it was a very shattering experience—I realized the media lies. And then watching what the media did to him, you know. They really tried to chew him up, and fortunately were very unsuccessful.

But several really exciting things happened during those years as a docent at the museum. And believe it or not, I was usually given the foreign students because I had less of an accent than anybody else. [chuckling] and I suppose that‘s because I‘d gone to school in Kansas. But when the museum first opened, one of the groups I had was a group of Japanese students.

And Mr. Truman thought it was great fun to come swooping out of his office and steal your tour. You‘d be in the middle of giving a tour

38

and he‘d come in, and those eyes just sparkling, you know, and that funny, wry smile, and steal your tour. And of course the tour group would just go wild, because here was the former President of the United States guiding them through the library.

But he stole this tour of Japanese students. And we got to the case on the atomic bomb, and one of the students . . . Oh, it was so hostile, you could have heard a pin drop. And one of those students stepped out of the group and said, ―Mr. Truman‖—didn‘t even call him ―Mr. President.‖ And he was jabbing his finger in the air, and he said, ―When are you going to apologize to my people for dropping the atomic bomb?‖ And to that point, President Truman had never made a public statement on the atomic bomb. He had never said a word about the decision. So he quoted the statistics, the number of casualties, the number of deaths, and he ended with the comment that he‘d made the decision and he‘d never been sorry. And he started down to the next case, and he stopped about halfway and he turned on his heel, and of course his eyes—had those real gray-blue, piercing eyes—and he turned around and he zeroed in on that kid and jabbed his finger in the air and said, ―Tell me, when are you going to apologize to us for Pearl Harbor?‖ And since then I‘ve noticed in many things he has used that same quote. But of course that was the first public comment, and I was standing right there. It was incredible. Of course, the media was with us. But that kind of thing over and over again, he‘d come out and steal your tour, and

39

somebody would ask him a question, and he would give his perception. So that to me, he moved from being Margaret‘s father to obviously being a historical figure, and probably going down in history as one of our strongest presidents. An amazing transformation, in my mind.

WILLIAMS: How long were you a docent over there?

GARD: I think it was a year and a half. I followed my then Navy physician husband to Hawaii, but I think I was there a year and a half or two years, the first two years of the library.

WILLIAMS: So you married a Navy physician?

GARD: Well, no, he wasn‘t even a medical student when I married him. [chuckling] He hadn‘t even been accepted to medical school, but we worked our way through.

WILLIAMS: And that‘s where you got the Gard name?

GARD: Right, right.

WILLIAMS: And we need another tape.

[End #4402; Begin #4403]

WILLIAMS: I don‘t think I could sleep with wet pajamas and the wind blowing over me.

GARD: [Jim is referring to the article in the Henhouse Hicks newspaper telling about Daddy soaking his pajamas in ice water and then sleeping under a fan. One way to deal with Missouri summers prior to air conditioning.] [laughter] I can‘t imagine. Well, Daddy was made of iron, I‘ll tell you. My goodness. No, we‘ll have to find that, because it was great. It was just

40

great.1

WILLIAMS: Not everybody‘s father was a U.S. Senator. Did that seem to matter to you?

GARD: No, actually I don‘t remember it being a big deal at all.

WILLIAMS: What about when Mr. Truman became president? How did that change the neighborhood or?

GARD: Well, I guess I‘ll have to tell a story on myself, which is really embarrassing, but . . . [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: Go ahead.

GARD: I remember they came home to visit one time, and they probably came in by train, but the streets were lined ten deep on both sides out here on Delaware, everybody to see the president—you know, in quotation marks. And Mother probably had looked out the side window and seen somebody she knew out there and went out to talk to them. So I go out, in my pigtails and my shorts with my dog, looking for my mother, and I‘m accosted by a reporter from Life magazine. And of course I‘m sure they thought, ―Well, here‘s the perfect picture. Here‘s the little girl, you know, in her jeans and her pigtails down her back, and her dog, and she‘s come to see the president.‖ So this reporter says, ―Little girl, did you come to see the President of the United States?‖ And of course I looked at her as if she had totally lost her mind, and I said, ―The President of the United States? He is my next-door neighbor. I‘m trying to find my mother to see if I can go swimming.‖ [chuckling] My priorities were squared away. So, no, it wasn‘t

1 Barbara Allen Gard notes that she was referring to a ―Henhouse Hicks‖ Newsletter article about her father soaking his pajamas in ice water and then sleeping under a fan. One way to deal with Missouri summers

41

a big deal. It should have been. We should have all been incredibly excited, but it wasn‘t a big deal.

WILLIAMS: Did it create a stir when he was here in town and there would be Secret Service around and things like that?

GARD: You know, when he was first in office nothing changed. I mean, the old fence was still up, there was no security, or a minimum kind of security around the house. People actually walked into the yard and broke off their flowers, and limbs off the trees. And my best friend Prudy, that I mentioned a minute ago, and I were climbing on their back fence, and it was an old fancy wire-on-wood-runners. We were climbing on their fence and broke it. The wood was rotten, and the whole fence just caved in. And of course we ran like mad. I‘m sure Pru would deny to this day that she [chuckling] had anything to do with destroying the Truman fence, but the fence had to be replaced, and at that point they put up the iron fence.

But security, until the Puerto Rican shootout and then the Blair House assassination attempt, security was rather minimal. The big change, of course, was building the Secret Service house on the back of the lot, and then Pru and I would go back and visit with the Secret Service men all the time when the family wasn‘t there. And then of course they installed the electric eyes, which increased security. It was very nice. Living here, why, there was a great deal of security because of the Secret Service presence in the neighborhood. Then they rented the house across the street and were

prior to air conditioning.

42

across the street. But it wasn‘t the ominous kind of feeling that I‘m sure you would have nowadays being around a president. There wasn‘t that feeling of terror that the Kennedy assassination brought.

WILLIAMS: They didn‘t block off the street?

GARD: Not at all. No, you know that‘s what would happen now, there would be barricades for six blocks. Not at all, not at all. They would be right there at home and the traffic proceeded as usual. In fact, my former husband nearly went into history by running over the President of the United States at 5:30 in the morning. [chuckling] He was coming out the back driveway . . . We were both in the car, and he was coming out the back driveway, and here came Mr. Truman on his walk. And there was a hedge back there and Howard didn‘t see him, and just about got him. And the president just tips his hat and, you know, taps the front fender of the car with his walking stick and goes on. And of course the Secret Service is totally ashen. But he . . . out for his walk.

WILLIAMS: Is this the driveway on Delaware?

GARD: Yes, the right one. [chuckling] Very informal, you see. Very informal.

WILLIAMS: Would you still go over there and visit when Margaret would come back?

GARD: No. Of course, as I say, Margaret and my sisters were closer in age, and they all kept up, you know, kept contact. And I know several times when Margaret would come back they‘d all double date, but I was so much younger that I didn‘t keep track.

WILLIAMS: Just so I know when your sisters moved away from Independence and

43

wouldn‘t have been around to visit then, could you run through that? Were they all living here all the way into the ‗50s?

GARD: Well, everybody went away to school, and . . . Excuse me. [Interview interrupted by visitors Jack and Mary Sue Luff – several minutes of miscellaneous personal conversation not transcribed]

WILLIAMS: Did I tell you that Dr. Zobrist gave David Wallace permission to call him at home once? [chuckling] We got a kick out of that. Or actually the secretary gave David Wallace permission to call him at home.

GARD: What for? [laughter]

WILLIAMS: Well, because he tried to call him several times, and he stopped by, and all the time he was in this meeting, he was in another meeting. Finally she said, ―Well . . .‖ something like . . . I didn‘t hear him, but he said, ―Well, I‘ve been given permission to call him at home tonight.‖ [chuckling] Okay, back . . .

GARD: Okay.

WILLIAMS: Your sisters, you all went to college?

GARD: Yes. See, everybody went away to school.

WILLIAMS: At about age eighteen, I presume.

GARD: Right, eighteen, and all my sisters went to girls‘ schools and then graduated from university someplace. I‘m the only one that escaped the girls‘ school fate. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: Which ones did they go to?

GARD: Marie went two years to Stephens and then graduated from UCLA. Harriet

44

went a year to Stephens, a year to Monticello, one semester at the University of Kansas, and then Marg invited her to go back to the 1948 inauguration with her. Her professors in Kansas refused to allow her to take her finals early. She lost an entire semester‘s credit because she went ahead and went to the inauguration anyway. My father was provoked, to say the least, and she immediately transferred to the University of Missouri.

WILLIAMS: Good for her.

GARD: Yes. And I think it‘s hard for people nowadays to realize how solid-Republican Kansas was and how solid-Democratic Missouri was, but going to school in Kansas was like going to school in a foreign country. And then Monie went a year to Monticello, and then I think all three years, the next three years to the University of Missouri. And then I went all four years to the University of Kansas. And they taught a version of the Civil War I had never heard before. [laughter] It was really interesting. If I hadn‘t been such a good student, I think I probably would have flunked, because they certainly didn‘t teach it the way I had learned it.

WILLIAMS: Then did you all come back here after college?

GARD: Yes, everybody ended up coming back to Independence, and for a number of years we were all here, married, with our young families. It was really fun.

WILLIAMS: Living in other houses, I presume.

GARD: Yes, yes, but living fairly close. All of us in . . . or at least three of us in one

45

area. So it was really fun.

WILLIAMS: So you would have had the chance, if you had been home from college, or your older sisters if they‘d been home, to visit the Trumans, and you would have been here to visit?

GARD: Well, and that‘s what would happen: everybody come home for holidays, and then, as I say, the older girls would double date and all of that.

WILLIAMS: So you would see them, when they were in the White House but back here.

GARD: Yes, right.

WILLIAMS: During those years.

GARD: Right.

WILLIAMS: And they hadn‘t changed much?

GARD: Well, of course my contact was with Mrs. Truman in those years, until I had contact with him at the library. And I don‘t think she ever changed. That‘s why I say she always to me was the same gracious lady.

WILLIAMS: You mentioned Harriet was invited to the inaugural in ‘49?

GARD: Yes, it would have been in January of ‘49.

WILLIAMS: Were any of your other sisters or you invited to Washington?

GARD: No, no, just Harriet, right. And I think Marg took another friend. I‘m not sure who it was. I believe her name was Jane. I don‘t recall exactly who that was. But of course, she was taking them back as her friends.

WILLIAMS: Was Harriet the closest to Margaret, as far as friends?

GARD: Yes, in age. Actually, Marg‘s age is between Harriet and Monie, but closer to Harriet, yeah.

46

WILLIAMS: So they were the closest friends.

GARD: Right.

WILLIAMS: What happened after the Trumans came back here to retire? Would you still see them?

GARD: Well, of course he was so involved in the library, and I think she just reassumed her life, the same bridge club and . . . same as Mother does. You know, Mother plays bridge a couple of days a week, and that‘s what Mrs. Truman did was play bridge and visit with her friends, picked up life where they left off.

No, it‘s interesting, you think about the difference. They had no independent source of income. He needed to get his memoirs written as quickly as possible because he needed the money. They didn‘t have a pension or retirement. Of course, he is one of the few elected officials in the world that didn‘t garner a fortune while he was in office, because he was an honest man. And it‘s incredible to think about it, but here he was, former President of the United States and . . . And he often cited the instances of John Adams‘s papers being sold off to support the family because there was no money, and of course Jefferson dying in poverty. So I was very glad to see some provision made. But no, they came back, no security. The only security they had, they were provided Mike Westwood from the Independence Police Department as a driver and personal security. So quite different from nowadays.

WILLIAMS: Have any of you kept up with Margaret through the years?

47

GARD: I don‘t know whether Harriet has or not, but not to any degree that I‘m aware of. I expect Mary Shaw probably has kept up more than anybody else.

WILLIAMS: Do you know her?

GARD: Sure. Oh, of course. How could I not? [chuckling] Shawsie, right. And a tomboy, you see. A girl after my own heart.

WILLIAMS: Somebody else we‘ve interviewed is Dorsy-

GARD: Dorsy Lou? Sure. Well, see, Comptons, they bought the Dunn house down the street on Delaware. And her little sister was Monie‘s very best friend, Lucy Jane.

WILLIAMS: There again, she‘s quite a bit older than you.

GARD: Dorsy Lou?

WILLIAMS: Dorsy.

GARD: She‘s Marie‘s age or maybe one year older than Marie, so she‘d be twelve years older.

WILLIAMS: She told us about having parties in that big house. Do you remember—

GARD: In the Comptons‘ place? No. No, as I say, see, I was so much younger.

WILLIAMS: The parties you recall were at the Jennings house?

GARD: Right, right.

WILLIAMS: Well, has it really changed your life, knowing the Trumans or being associated with them?

GARD: I think the thing I gained—of course a lot of it‘s from my father, because my father was very well-read, very interested in lots and lots of things. He

48

didn‘t do a lot of traveling. He always talked about doing a lot of traveling. He was very interested in archaeology. It‘s kind of interesting because my son is an archaeologist, anthropologist. I wish he could have known his grandfather. They would have had a lot of things to talk about.

But I think knowing a president, knowing a sitting president, made me a lot more interested in what was going on, made me pay attention to what was going on. And I think I chose history as my major, I think there was some of that as an influence. I used to have to leave parties in the Navy all the time because the first question you were asked was: ―Where are you from?‖ I‘d say, ―Independence, Missouri.‖ They‘d say, ―Harry Truman,‖ and start criticizing him. I would say, ―He‘s going down in history as one of our strongest presidents,‖ and the fight would get so hot we‘d have to leave the party. I know it influenced my point of view.

One of the things that I think Harry Truman, my father, probably all of us gathered from the atmosphere of growing up was how important this business of integrity is, that meeting your obligations, being responsible. It‘s almost a Cyrano de Bergerac white plume syndrome, but how integrity is the most important thing in the world. And I know I can see Harry Truman‘s eyes right at this moment, and I know nobody ever bullied that man. No matter how afraid he must have been for his wife or his child—and there were kidnapping attempts on Margaret—I‘m sure nobody every bullied him. Because his priorities were just absolutely clear in his own mind as to what to do and what not to do. The same was true of my father.

49

I feel that very strongly. When I served as an elected official, no one could have bought my vote. It‘s just . . . that‘s unspeakable. It‘s unthinkable. And I think a lot of that sense of history, that sense of purpose, that sense of integrity, that sense of public service . . .

When you talk about elected officials nowadays, public service doesn‘t even seem to enter into it. But it definitely did with him. He was an anomaly in this part of the country because he was an honest elected official. This whole area assumed graft and corruption was . . . It was like Chicago, you know, where the definition of a crooked politician is one that takes a bribe and doesn‘t stay bought. It‘s the same kind of atmosphere here. And really decent honest people that should have spoken out and didn‘t, they just accepted it as a way of life. He never did. He never did. Even if he was involved with these people, he never did. He never sold out. And I think I really felt that very strongly.

In the conversations I heard about him, as I say, the shock waves when he was elected, because he was honest. And that‘s so important. And I think his teaching the six different jobs of the presidency, that was always so important to me to teach that in the classroom. And I notice that every government textbook I ever used used those six parts of the presidency. His idea of history and the sense of history, the big picture, he saw the big picture rather than the ―I have to get reelected‖ kind of picture. It was less important to him to win than it was to do what was right. And I think those are the things I really gained from being next door to him. I read a lot more

50

than I would have, as young as I was, if he hadn‘t been next door. And I heard my father talk about it a lot more than I‘m sure we would have.

WILLIAMS: Did he encourage that directly, Mr. Truman? Did he ever talk to you about schooling?

GARD: He talked about it all the time when he was back in the library, that business, and of course he would take time to talk to students at the drop of a hat. And he constantly talked about the big picture, about the sense of history, about responsibility, about the enlightened population.

You stop and think about it now, and these are people, my dad and President Truman both, they came from farms, came from poor families. They worked terribly hard for their own educations. Education was just primary. And that business of believing in the system and participating in the system, and public education, those were just values that were absolute . . . Marg didn‘t go to private schools. My sister didn‘t go to private schools. You know, there was just a whole sense about involvement with the people around you and service. Dad‘s service was medicine, President Truman‘s was government. But that was a real part of their personalities and of their feelings.

WILLIAMS: You mentioned the occasion when Mr. Truman and your father were here visiting at the dining room table. Were there other occasions like that, that you recall?

GARD: Oh, yes, but I particularly remember that conversation because of the use of a word that I didn‘t know and the obligatory looking it up. And I had no

51

idea at the time the significance of that conversation. And I thought about it years later, how overwhelming that must have been. I mean, here was a senator who was very high-profile, of course, because of the Truman Committee and all of those hearings, but who really had no idea what the state of Roosevelt‘s health was, who thought he was going to be a vice president like Garner or any of the others and just go down in history, like Dawes, with nobody ever knowing who, what, or where. And he had been on center stage and felt like he was making important changes, and now he was going to oblivion, and how far from the truth that was. And how really smart it was of Roosevelt, if he thought the thing through, to have chosen somebody who had the moral backbone and the courage to do what was going to have to be done. Truman saved Europe. He saved Europe. And so it was an incredible choice on Roosevelt‘s part.

WILLIAMS: Were your parents and the Trumans just . . . their relationship just like neighbors?

GARD: Right, right.

WILLIAMS: Close neighbors, or just . . .

GARD: Just neighbors, very nice, friendly relationships. But people didn‘t visit back and forth a lot. As I say, the ladies played bridge, but they didn‘t coffee klatch, that sort of thing. They were running big households, and of course, in my mother‘s case, lots of children, and of course older parents to care for, and lots of family around. You know, you did lots of things with family. So no, there wasn‘t a lot of visiting back and forth, but

52

relationships were always very cordial.

WILLIAMS: And you‘ve already mentioned that they were invited to weddings and—

GARD: Yes.

WILLIAMS: Was your family invited to Margaret‘s wedding, for instance?