Last updated: January 14, 2025

Article

Bad River Encounter Site—“The West” Moves East

Wikimedia Commons

Traveling westward on the Missouri River from its “Big Bend” to the mouth of the Bad River, the expedition crossed the 100th meridian of longitude. On September 24 and 25, 1804, they experienced tense interactions with members of the Teton Lakota. At this time, the Lakota practiced a nomadic, horse-based culture that would become emblematic of the high plains environment and symbolic of the American West. The idea of “the West” in the American popular imagination has also been tied to the process of the westward-moving frontier, driven by exploration and settlement.17

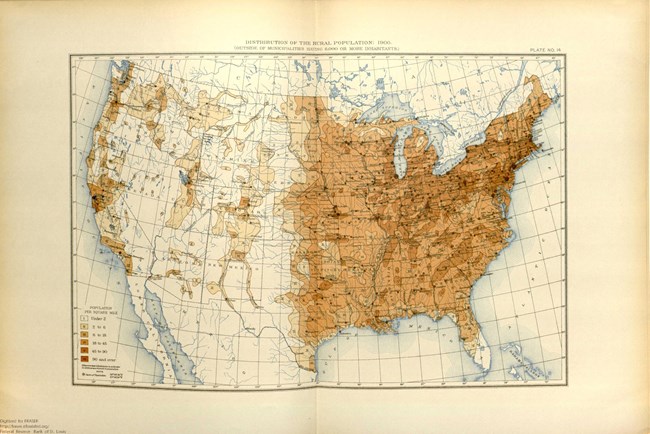

In 1878, geologist John Wesley Powell used the 100th meridian to mark a boundary between the humid East and the arid West. West of this line, annual precipitation usually amounted to less than twenty inches, the minimum amount needed for agriculture without irrigation. The line also marked a decline in population numbers from east to west. From here to the Rocky Mountains, European American settlers adopted dryland wheat farming and free-range cattle, filling an ecological niche once occupied by grazing bison that had supported the Lakota and other Indigenous peoples on the Great Plains.18

Using data collected since 1980, scientists now suggest that this line of minimum rainfall has shifted eastward due to climate change. As temperatures rise, evaporation increases, pushing the boundary closer to the 98th meridian, about 140 miles eastward. It is expected to move another two or three degrees of longitude by the year 2100. This change will likely affect crop types, farm size, water demand, and even population in the area. The shifting boundary of “the West” once reflected westward national expansion. Now moving east, it illustrates the environmental, economic, and social consequences of climate change.19

Citations:

17 NPS, “Bad River Encounter Site,” Pittsburgh to the Pacific: High Potential Historic Sites of the Lewis and Clark National Historical Trail, 2022, 53, https://www.nps.gov/lecl/getinvolved/upload/2022_LCNHT_HPHS_Report_508compliantUPDATE-2.pdf; William Clark, September 25, 1804 entry, in Gary E. Moulton, Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, https://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1804-09-25.

18 Harvey Leifert, “Dividing Line: The Past, Present and Future of the 100th Meridian,” Earth: The Science Behind the Headlines (January 9, 2018), https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/dividing-line-past-present-and-future-100thmeridian.

19 Kevin Krajick, “The 100th Meridian, Where the Great Plains Begin, May be Shifting,” State of the Planet (Columbia Climate School), April 11, 2018, https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2018/04/11/the-100th-meridian-where-the-greatplains-used-to-begin-now-moving-east/; Richard Seager, et al., “Whither the 100th Meridian? The Once and Future Physical and Human Geography of America’s Arid-Humid Divide, Part II: The Meridian Moves East,” Earth Interactions (American Meteorological Society) 22, no. 5 (March 1, 2018): 1–24.