Last updated: October 30, 2020

Article

Around and About James A. Garfield: Whitelaw Reid (Part I)

Wikipedia

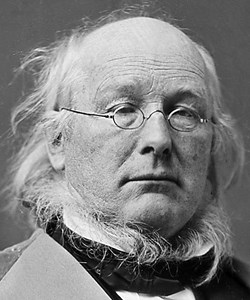

This is the inaugural article in a series of occasional blogs that will offer a biographical sketch of individuals who influenced the life, career, and decisions of James A. Garfield. This series begins with a look at Whitelaw Reid, most noted as the editor of the New York Tribune for forty years, from 1872 to 1912.

Reid was born in Xenia, Ohio on October 27, 1837. His mother wanted to name him “James,” but his Baptismal Certificate shows only the name “Whitelaw.” Yet, he used the name “James” throughout childhood. In early adulthood, he began using Whitelaw as his name, and was sometimes known simply as “White.”

Dickinson College

He attended the Xenia Academy in his youth, studying Latin, classical literature, and mathematics. At fifteen he was well enough prepared for entry into Miami University, at Oxford, Ohio, as a second year student. While at the school, Reid joined a literary society whose members enjoyed discussing politics and public speaking. He graduated with honors in 1856. Though his studies did not indicate a career in journalism, by the early 1860s Reid was writing for the Cincinnati Gazette, the Cincinnati Times, and the Cleveland Herald, under the pen name “Agate.” (Agate is a translucent rock of varied colorful layers.)

During the Civil War, Reid acted as a correspondent at several battlefields, among them Shiloh and Gettysburg. His account of the Battle of Shiloh, with tales of confusion, courage, and disaster narrowly averted, has been described as classic war reporting.

The war years affected Reid directly. His older brother, Gavin died in 1862, though not on the battlefield. His father died in 1865. Reid was now responsible for the care of his mother, who was in her sixties. The results of the war also led him to attempt a “get rich quick” investment in a southern plantation in 1866. At the same time, Reid took up his talent with his pen to compose After the War and Ohio in the War. His experiment in the South was not profitable, and within two years he took the step that made his an influential voice in American society and made him a confidante to political figures, including James G. Blaine and James A. Garfield.

Like other white northerners, Reid betrayed a mix of opinions and attitudes toward black slaves, and African-Americans in general. Prior to the Civil War his experience of blacks had been little. He was opposed to slavery, and supported Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation. He did not think, after the war, that universal suffrage for black men was wise, but he also knew of many “orderly and respectable” blacks who he felt were worthy of the right to vote. He favored education for the former slaves but had doubts about their capabilities. “The negroes do not have the intelligence and the white do not have the inclinations to secure for the blacks the full benefits of any educational provisions that may be made for them.”

Though today many Americans would find this attitude highly prejudicial, in Reid’s day it was commonly held, even among those whites who wanted justice for African-Americans.

In the South, he found the former rebels to be still rebellious, and yet he thought that northern military domination the white “elite” during Reconstruction was a mistake. At the same time, he was in accord with many northerners who were sure that allowing the southern elite to regain political control spelled disaster for blacks on the local level, and repudiation of Confederate debt on the national level.

The year 1868 was a seminal year for Reid. This tall, slender man with a drooping mustache, long black hair, and “intelligent eyes” joined the staff of Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune. The following year he was named managing editor. In 1872, Reid was part of the Liberal Republican movement that opposed a second term for President Grant and that ultimately supported the ill-fated Greeley for the presidency. Greeley died just days after the election and a short time later Reid became the new editor of the Tribune.

Wikipedia

Greeley’s disastrous candidacy and death caused the circulation of the daily Tribune to decline greatly. It was Reid’s task to revive it. This took years. Complicating his ability to achieve that goal were several factors. Disputes between himself and the typesetters union and his unskilled laborers arose on several occasions. In 1877, he proposed wage reductions to save costs, knowing that the unionized work force would resist him. When a new Tribune building was under construction during this time, he replaced striking workers with Italian immigrants who worked for less. Reid’s clashes with unions and his workers persisted throughout the 1870s and 1880s. Insisting that “authority” must be maintained, he favored strong action against striking workers during the Railroad Strike of 1877.

Of the many presidents Reid would come in contact with, the first was Hayes. Reid thought Hayes was an excellent choice for the Republicans in 1876. He regarded Hayes as a gentleman and an honest man, if not a great one. He assured Hayes of the support of the Tribune during the election, and initially approved of Hayes’ desire to reform the civil service. However, after Hayes became president, articles appeared in the Tribune critical of the overzealous reforms of Carl Schurz, the Secretary of the Interior.

Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center

In 1880, Reid and the Tribune were strongly opposed to the nomination of Ulysses S. Grant for a third term as president. (President Hayes did not wish a second term.) James G. Blaine appeared to Reid to be the best hope for a Republican victory, but the nomination went to James A. Garfield. Immediately, Reid began to council harmony within the party and to advise the nominee. He urged Garfield to remain at his Mentor, Ohio home for the duration of the campaign. It was a tradition that presidential candidates did not campaign for themselves, and Reid knew that Garfield would have liked being “on the stump.” Whether from Reid’s influence or not, Garfield did indeed remain at home, resulting in the first front porch presidential campaign. The innovation proved to be successful. Garfield and Reid consulted regularly during the campaign and in the months leading to the president-elect’s inauguration.

Reid offered Garfield his take on two opposing figures in the Republican Party. Do not put too much stock into Carl Schurz and his ties to the German vote, Reid advised, opining that Schurz had done Hayes more harm than good. New York’s senior Senator, Roscoe Conkling, was another concern. Reid cautioned Garfield that Conkling could not be given too much influence in future New York political appointments, but recognized that “he is undoubtedly of great value on the stump…”

Garfield, for his part, respected Reid’s political sagacity and position as the editor of an influential newspaper. His view of civil service reform closely followed Reid’s. Garfield favored reform, but also acknowledged the value of consulting congressional opinion in the process of making appointments.

Reid was of good service to Garfield as he began forming his cabinet amidst the competing cries of the many factions of the Republican Party. Reid agreed with the incoming Secretary of State, James Blaine, that a way to satisfy moderate Republicans, and Conkling’s demand for a New York appointment, was the selection of Thomas L. James as the Postmaster General. James initially accepted. Then he received a tongue-lashing from Conkling and backed out. Later, he thought it over and accepted again. None of this pleased Conkling, who resented Reid’s influence with Garfield. As Reid’s biographer, Bingham Duncan, put it, “Reid happily described [Conkling’s] discomfiture to Miss Mills [Reid’s fiancée] and added, ‘G. told me of it with a chuckle.’”

Early in 1881, Mrs. Garfield traveled to New York to purchase dresses for the Inauguration. She stayed at Reid’s home, with her companion, Mrs. Sheldon. Upon her return to Mentor, Mrs. Garfield received a letter from Reid. It contained information on an overcharge of more than $100 from one of the companies Mrs. Garfield visited, with an additional mention of a bill from Tiffany.

In the same letter, Reid wrote that he had “met Mrs. Hayes at dinner last night. She told me of people coming to her about your policy on wines & her advising them to keep away from you. But, speaking for herself, & without any idea of its ever reaching you, she spoke very frankly of her belief that it would be a mistake to change [Mrs. Hayes’ practice of forbidding alcohol to be served in the White House]. She thought it would cost about five thousand votes in Ohio.”

Wikipedia

Whitelaw Reid’s most consequential advice to the new president, supported by Blaine, was his urging that William Robertson be appointed as Collector of the Port of New York. Robertson had opposed Conkling and his preferred nominee, former president Grant, at the 1880 Convention. Now he was being touted for the most important appointed position in the federal government. It was a direct attack on Conkling and caused a big fight between the President and the Senator, and further disrupted the Republican Party. When, in April, Reid was asked to persuade Robertson to withdraw, he opined to John Hay, one of Lincoln’s former secretaries, and a good friend, that sticking with Robertson would be “the turning point of [Garfield’s] Administration… the crisis of his Fate.”

Though ultimately President Garfield won his battle with Conkling over the Robertson appointment, “Fate,” in the human form of Charles Guiteau, was not kind him. The assassin pointed to the battle with Conkling over patronage as part of his “inspiration” in shoot the President.

After Garfield’s death, Reid advised Blaine to resign from the cabinet. He opposed President Arthur’s administration and supported Blaine for the presidency in 1884. Until then, Reid refocused his attention on the Tribune, and particularly on the promotion of a technological advancement invented by a German immigrant living in Baltimore at the time, Ottmar Mergenthaler.

Using a keyboard similar to that found on a typewriter, hot lead was molded into lines of type. The process was much faster than having typographers set the lines in a composing stick one letter at a time.

The editors at the Baltimore Sun rejected Mergenthaler’s new technology, but the editor of the New York Tribune embraced it. Whitelaw Reid promoted the new “linotype [line-of-type] machine,” and the helped to establish the Mergenthaler Linotype Company. In taking up the efficiency of Mergenthaler’s invention, Reid opened up another controversy with the Typographical Union #6, for the linotype machine meant a cut in wages for typographers, the men who arranged the type to be printed. Negotiations between Reid and the union produced the usual results: charges of bad faith and walk-outs. Type founders, the men who made the type, and newspaper proprietors, saw nothing wrong in cutting the wages of typographers, since the linotype machines was doing the work previously done by them. The issues between Reid and his typographers were not resolved during the 1880s.

Both Hayes and Garfield had offered Reid a diplomatic post in Germany, which he refused. He was without influence during the Arthur and first Cleveland presidencies, but after Benjamin Harrison’s election in 1888 Reid made no secret of his desire to be Ambassador to Great Britain. He was offered the post of Ambassador to France instead; it was accepted.

At this time, Reid held to a limited role for the United States in international affairs. Like many of his contemporaries during the post-war years, he did not see a need for the influence of the United States to extend beyond North and South America. He favored a small navy and opposed the acquisition of Hawaii by the United States (an instance in which he agreed with President Cleveland), but he understood the importance of an isthmian canal in Central America. Though an admirer of the English, he cast a wary eye on Great Britain and its desire for a presence, and influence, in Latin America.

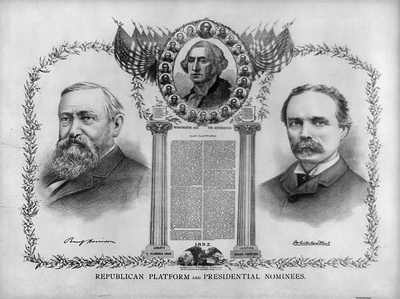

Reid’s tenure in France served the country well. In 1892, this seasoned newspaper editor and successful diplomat was chosen as President Harrison’s running mate in a bid for the president’s reelection. He was a more active candidate for Vice President than Harrison, whose wife was dying, was for President. Reid credited the Republican Party as the party that freed the slave and preserved the Union, protected labor [surprising inclusion from a man who cut wages and hired scabs], promoted manufacturing, built the railroads, instituted the all-steel navy, and more. Despite Reid’s efforts and those of other Republicans, Harrison lost the election. It was a blow to Reid, who for a time withdrew from public life.

In 1896, with William McKinley’s election to the presidency, Reid expressed an interest in becoming Secretary of State. Senator Platt, of New York, the Republican strongman of that state, opposed the idea: “I told [Mark] Hanna [McKinley’s most important adviser] to tell McKinley if he wanted Hell with the lid off… to appoint Reid.” John Sherman was appointed Secretary of State instead; Reid was also passed over for the post of Ambassador to the Court of St. James’s. While this second slight by McKinley left Reid bitter, his disappointment was assuaged a bit when he was appointed to head the mission sent to Great Britain to attend the ceremonies for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee.

(Check back soon for Part II!)

Written by Alan Gephardt, Park Ranger, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, February 2016