Last updated: July 27, 2020

Article

Caribou Resource Brief for the Arctic Network

Kyle Joly/NPS

NPS

The status of caribou in the Arctic Network

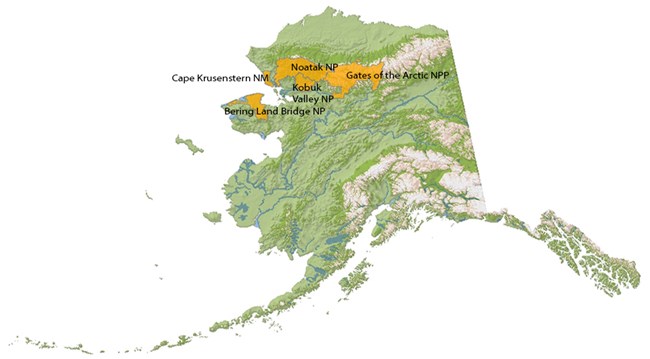

The Western Arctic Caribou Herd (WAH) uses all five Arctic Network (ARCN) parks. Spring migration typically takes the herd north through Kobuk Valley National Park and Noatak National Preserve to reach their calving grounds. Interestingly, the timing of spring migration is synchronized with other caribou herds across the North American Arctic. Caribou exhibit the longest terrestrial migrations on the planet; some populations travel over 1500 km (930 miles) between their calving and wintering grounds and back. Caribou seemingly never stop moving, with some WAH caribou covering up to 4400 km (2730 miles) in a year based on their GPS track. Caribou typically cross the Kobuk River again, often at the historic Onion Portage archaeological site, each fall during their southward migration. However, for reasons unknown but that we currently study, the number of WAH caribou migrating south across the Kobuk River has dramatically declined recently.New discoveries on caribou movements in the Arctic

Caribou will shake, walk, and even run away from insects. Often, they will go to habitats with little vegetation, like river gravel bars and snow fields, and group together in the hundreds of thousands to reduce insect harassment. But more time spent avoiding insects in poor habitats, means less time to feed during a short growing season. If caribou don't get enough to eat during the summer, their calves can have lower survival rates and cows can fail to gain enough weight to be able to become pregnant in the fall. This could negatively affect the entire population.

https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/bugpower.htm

Kyle Joly/NPS

NPS

Why caribou are important

Many Alaska Natives in this region identify themselves as “caribou people”. Caribou are ingrained in their history, traditions, and psyche. Approximately 15,000 caribou are harvested annually from the WAH by local rural residents living a subsistence lifestyle. Herd size naturally oscillates, which may be related to climatic cycles such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (see graphic). In 1976, the herd reached a population low of 75,000 animals. It quickly rebounded to become one of the largest herds in the world, nearing 500,000 animals in 2003. Since that time, it has declined to 244,000 in 2019 resulting in restrictions in sport and subsistence harvests. Despite the decline, the WAH continues to have a significant role in the structure and function of ecosystems in northwest Alaska. A herd of this size can substantially affect its habitat, which covers all of northwest Alaska (over 360,000 km2), its primary predators (wolves and grizzly bears), as well as a suite of other animals through cascading trophic effects. For example, decreasing abundance of caribou could lead to fewer wolves, which could impact the abundance of the foxes or beaver.

Kyle Joly/NPS

How we monitor caribou

National Park Service (NPS) began assisting with the monitoring of Western Arctic Herd (WAH) caribou in the 1980s, shortly after the northwest Alaska parks were established. In 2009, the NPS ramped up and formalized their monitoring efforts and, for the first time, deployed GPS collars in conjunction with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG). Over 300 GPS collars have since been deployed that have collected over 800,000 caribou locations.The location data helps us to define seasonal ranges, migration routes and timing, and survivorship of adult females.

Tina Moran/USFWS

What we want to know about caribou

Our goals are to monitor the movements, distribution and health of WAH caribou in ARCN parks. The timing and spatial pattern of the herd’s migration is critical in the harvest of caribou by rural residents. Changes to these patterns may affect these subsistence users, the vitality of the herd, and the ecosystem.Objectives:

Collar WAH caribou to maintain a sample size of 30-40 GPS collars.Obtain frequent (>2/day) location data via GPS-satellite telemetry.

Define seasonal ranges (calving, insect relief, summer, winter).

Define migratory routes.

Detect changes in range distribution over time.

Detect changes in adult survivorship over time.

Detect changes in migration routes and movement phenology over time.

Kyle Joly/NPS

How monitoring caribou can help park managers

The WAH is one of the most critical subsistence resources in northwest Alaska. Monitoring the herd helps develop subsistence and sport hunting regulations that conserve the resource, protect critical habitat, and reduce conflicts among user groups. NPS monitoring of the WAH has resulted in dozens of published studies on caribou ecology and factors that influence it such as human development, climate change, harvest, snow, wildfire, lichens, and more. These reports are available at: https://www.nps.gov/im/arcn/caribou.htmContact Information

Kyle Joly

kyle_joly@nps.gov

Tags

- bering land bridge national preserve

- cape krusenstern national monument

- gates of the arctic national park & preserve

- kobuk valley national park

- noatak national preserve

- caribou migration

- arctic network

- arctic

- arctic science

- gates of the arctic national park and preserve

- noatak national preserve

- kobuk valley national park

- cape krusenstern national monument

- western arctic caribou herd

- western arctic parklands

- northwest arctic heritage center

- bering land bridge national park service

- bering land bridge national preserve

- resource brief

- vital sign

- alaska

- caribou