Last updated: June 4, 2025

Article

Centuries of Human-Caribou Relationship, Migration, and the Conflict Today’s World Brings

- Emily Creek, Cultural Anthropologist, Western Arctic Parklands

- Raime Fronstin, Wildlife Biologist, Western Arctic Parklands

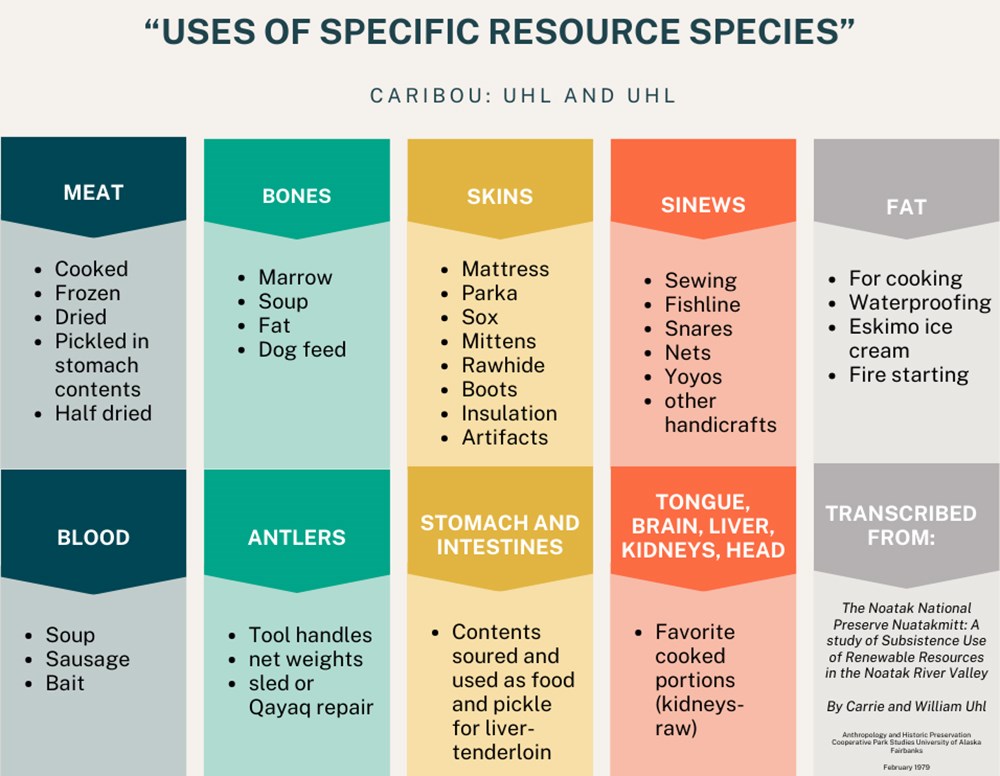

The importance of caribou has been well documented in the region. Ernest Burch Jr. and Don Foote kept careful records of caribou use during their research years (Burch et al. 1999, Foote 1965). Caribou subsistence and its relevance to local users is more complex than simply the number of caribou harvested to sustain the nutrient and clothing needs of a community. For example, local knowledge includes specifics of what caribou to harvest, when to harvest, and for which items (Figure 1).

(Uhl and Uhl 1979)

Pre-Park Research

In the first study done for the National Park Service (NPS), Bob and Carrie Uhl (1979), emphasized humans and their subsistence activities as part of the ecosystem when weighing the potential new ANILCA legislation. They argued that because humans have been a part of the ecology for thousands of years, to not include their role in the ecosystem, “smacks of artificialization rather than preservation" (Uhl and Uhl 1979: 57). They highlighted the intricate knowledge of the land and rivers navigated for use as hunting grounds to provide niqipaiq (native food), such as caribou, moose, and fish.In 1979, Jim Magdanz completed a fellowship in Northwest Alaska during the time when ANILCA was being drafted. In his writings, Magdanz addresses the new obstacles brought about by state and federal land ownership and the conflicting concepts of wilderness among different user groups. Although the NPS and Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) drafted regulations to recognize subsistence, residents were concerned that these wouldn’t have the flexibility to keep up with fluctuating animal populations and changing needs of communities. Different user groups had distinct apprehensions.

Closing the parks and monuments to sport hunters forced them onto smaller swaths of land used for subsistence. Environmental groups were concerned that motorized forms of transportation would spoil the wilderness experience.

Conservation groups believe that harvesting animals, even for subsistence, is an ugly and obsolete part of our heritage. To which the NPS subsistence specialist at the time, Ray Bane, replied: 'Man can be a non-destructive part of the wilderness. He can be. There’s a blanket of culture all over this area, an invisible blanket. When floaters float these rivers, they say, Look at this untouched land. It’s not untouched. It’s just been touched gently. Why not let it continue?'

NPS/Adam Freeburg

Studying Conflicts in the Preserve

Three studies have examined the history of conflict between user groups in the preserve, 2 of the 3 interviewed different user groups about their use of caribou and perceptions of hunting. In 2015, Fix and Ackerman did a study on the non-resident sport hunters who used Noatak National Preserve. In 2015, Gabriella Halas for her MA thesis, looked at the issue from the perspective of subsistence hunters. Finally in 2021, Deur, Hebert, and Atkinson published a review of the literature relating to traditional caribou hunting. These studies identified three major conflicts (1) aircraft use, (2) differences in hunting practices, and (3) spatial overlap of different hunter groups.Aircraft Use

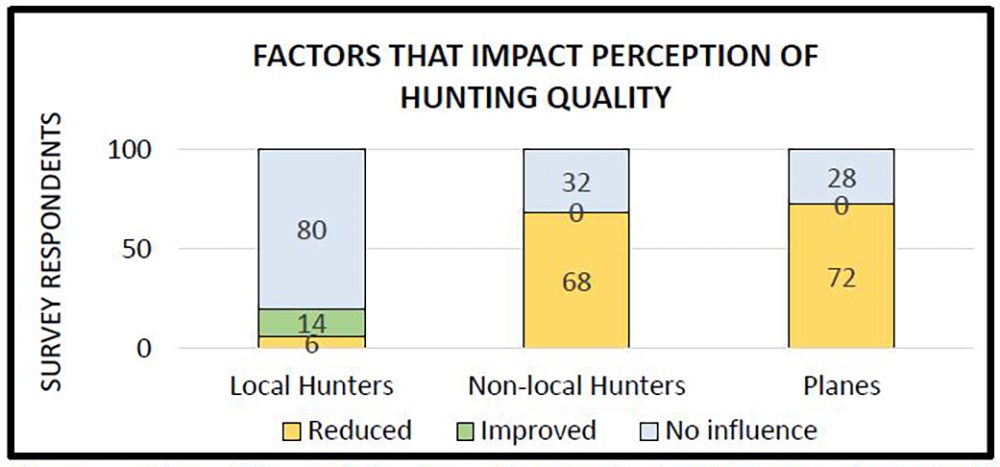

A long-standing and widespread conflict in Arctic Alaska involves the use of aircraft by non-resident sport hunters to access caribou and the resulting disturbances to local subsistence hunting. Communities across the region have consistently expressed concern that low-flying aircraft disturb caribou, interrupt migration, and divert animals away from traditional hunting areas, ultimately reducing harvest success for local hunters (Stinchcomb et al. 2019).Traditional Knowledge (TK) provides strong support for these concerns. In a study conducted by Halas (2015), interviews with 113 active hunters and 20 knowledgeable elders from Noatak revealed that most respondents perceived aircraft as having a negative effect on hunting success (Figure 2). Aircraft were reported to startle caribou, delay or divert migration away from the Noatak River, and disturb movement patterns—especially when landing sites and sport hunter camps were situated within migratory corridors. Similarly, Georgette and Loon (1988) found that hunting areas used by Noatak residents in 1987 remained consistent with those reported by Foote in 1965, indicating long-term reliance on specific river corridor locations now increasingly disrupted by aircraft.

(Halas 2015)

Comparative studies have also shown that the Western Arctic Herd, which has had less exposure to aircraft, fled more frequently and for longer durations than the more habituated Delta Herd (Valkenburg and Davis 1985), though habituation is likely one of several influencing factors. Regardless, repetitive aircraft disturbance on caribou has the potential for deleterious short and long-term effects. In addition to the risk of direct physical injury resulting from panic responses, it is well established that elevated stress can have lasting detrimental effects on animal health and reproduction. For example, in one study the variance in calf survival was explained by the exposure frequency of cows to low-level jet flights over certain biologically sensitive periods (Harrington and Veitch 1992). Disturbances during energetically demanding periods—such as insect harassment and late winter—could be particularly harmful, as increased activity may lead to the depletion of critical energy reserves. To mitigate these impacts, multiple studies recommend that flights remain above 1,000 feet AGL, with some responses during insect harassment, observed as high as 2000 feet AGL (Calef et al. 1974, Jakimchuk 1980, McCourt et al. 1974a). Maier (1996) recommended prohibiting overflights altogether during sensitive biological periods.While these studies demonstrate that aircraft—especially low-flying planes—can affect caribou behavior and potentially long-term health and localized caribou movement, there remains a critical gap in linking these effects directly to quantitative impacts on subsistence harvest success.

To further understand the scope of aircraft presence in relevant areas, Stinchcomb and others (2020) conducted acoustic monitoring around a subsistence-based community in Arctic Alaska. They found that aircraft significantly altered the acoustic environment in traditional harvest areas, with noise levels highest near human development and decreasing with distance. Further, the area with the highest harvest usage (within 30 km of villages in Stinchcomb’s 2020 study) overlapped with the area of the highest aircraft activity. Thereby, leading subsistence users to travel further from their villages and traditional hunting grounds to escape disturbance.

Though causal links between aircraft disturbance and harvest outcomes are absent in peer-reviewed literature, the collective evidence—including TK, behavioral studies, and acoustic data— show that (1) subsistence users across the Arctic have consistently reported observing aircraft activity disturbing caribou and diverting local movement, (2) aircraft conclusively can affect caribou behaviour, and (3) there is a lot of aircraft activity around villages and traditional hunting grounds. Even in the absence of definitive causal links between aircraft disturbance and harvest, given the evidence that we have, precautionary measures are reasonable. Mitigating the potential impacts of aircraft on harvest can be achieved by implementing minimum recommended flight altitudes when flying over caribou habitat and establishing buffer zones that limit unnecessary aircraft activity within approximately 20 miles (30 km) of villages (or average area of customary use). However, because airspace regulation falls under the authority of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), success would depend on outreach, education, and the voluntary compliance of pilots.

Ultimately, this conflict centers on the availability of caribou to local subsistence users and concerns over disruptions to traditional harvest success. Under the rural priority established by the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), these concerns remain legitimate, urgent, and unresolved.

Difference in Hunting Practices

Another issue is in the perception of non-resident sport hunting vs. subsistence hunting. Subsistence users have depended on the WACH for millennia. Herd declines have major effects on the food security of local communities. The people who live in Northwest Alaska cannot go elsewhere to obtain their staple resources and grocery store products are disproportionately expensive or unavailable. When they hunt, they have to search for caribou and may travel many miles by boat, snowmachine, or all-terrain vehicle (ATV). Hunts can take days to weeks and are not always successful. Fuel in remote Alaska is several times the national average (up to $15/gal at times). On the other hand, non-resident sport hunters have the means to pay to fly from around urban areas of Alaska and from around the world to come hunt the WACH. They are not reliant on the harvest as the main source of meat in their freezer. They have access to other hunts and grocery stores. When they arrive, they are dropped off by transporter service directly into an area that is known to have caribou, and each hunt is relatively quick and nearly always successful. ANILCA was written in part to address this issue:This issue comes to a head in part due to the difference in hunting practices between user groups. Nuatakmiit hunters believe in a world of spirits where non-human animals must be shown respect, and proper behavior toward prey is rewarded by successful hunts, while disrespect impedes success. Years of living as a part of the ecosystem has granted local subsistence users invaluable hunting knowledge that has been passed down through generations. Many Iñupiat and specifically Nuatakmiit continue to follow traditional rituals before, during, and after harvest. These practices are meant to aid in the success of individual hunters but also in the success of providing for others who depend upon the herd. In this light, non-resident sport hunters who don’t practice these traditions can affect the success of all of the hunters after them (Deur et al. 2021).

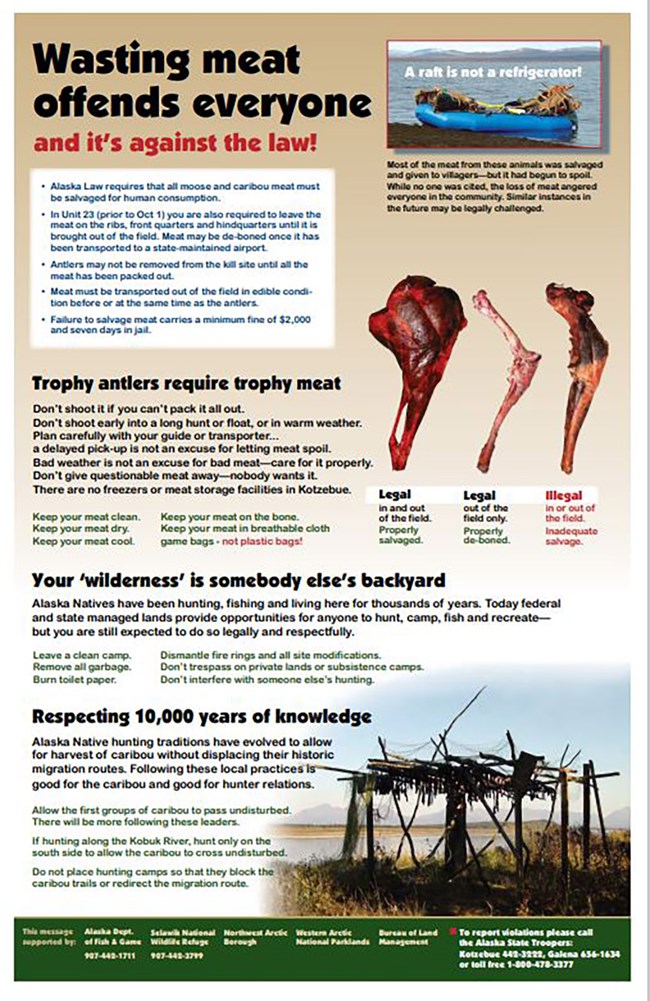

One of the most important traditions in caribou hunting is letting the first caribou leader of the herd pass unharmed. Public meeting records from the most recent 2023 federal regulatory cycle document 12 references to these specific practices, with one being a summary of public hearing testimony held in Kotzebue (FSB 2023, NPS CAKR SRC 2023, NPS KOVA SRC 2023, NWARAC 2023). During the testimony, most comments referenced this issue (FSB 2023). To address this, the park has a video that non-resident sport hunters coming into Noatak National Preserve to hunt caribou are asked to watch (Hunting - Noatak National Preserve (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)). The video emphasizes the importance of the area to Nuatakmiit subsistence hunters and asks visiting sport hunters to respect the tradition of allowing the first caribou to pass through a migration route unharmed. Lead caribou establish scent trails for the rest of the herd to follow; thus, if the first caribou is harvested, it prevents the migration route from being established. Unfortunately, this message does not reach all hunters who come into the area. It can also be hard for inexperienced hunters to identify lead caribou. In a poll given to sport hunters who have used Noatak National Preserve, when asked about following local traditions, almost 20% of respondents shot at the first caribou (Fix and Ackerman 2015).

Another hunting tradition, often unknown to non-resident sport hunters, is that local subsistence hunters allow the caribou to cross the Noatak River before harvesting them. Similar to hunting the first caribou, shooting at caribou before they cross the river can prevent the others from crossing. Many non-resident sport hunters are unaware of these practices, and this causes conflict between user groups. Agencies provide online media and flyers to transporters to resolve this conflict. But community members in Noatak and Kotzebue say it is unresolved.

Spatial Overlap of User Groups

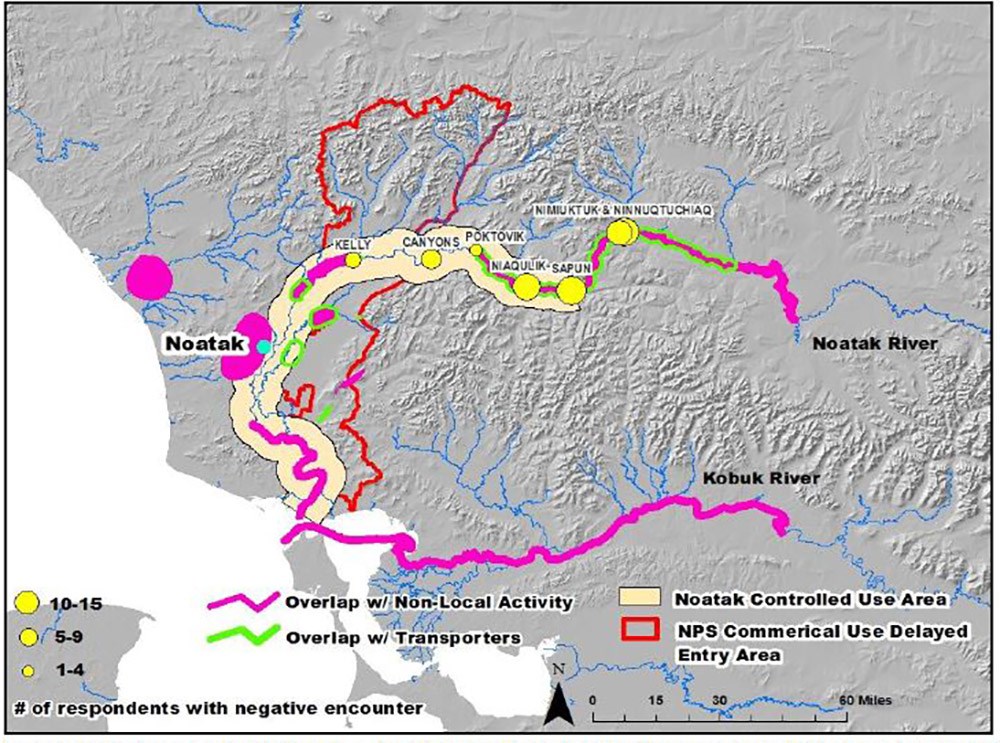

Conflict over spatial overlap of subsistence and non-resident sport hunters has been a long-standing issue that continues to this day (Halas 2015, Magdanz 1979). The location where non-resident hunters are being dropped by transporters was another of the main concerns during the 2023 federal regulatory cycle. Halas (2015) looked at locations of overlap between user groups in Noatak National Preserve (Figure 3). She interviewed Nuatakmiit hunters about areas they’d used in the last 5 years as well as lifetime use areas and compared them to areas with non-resident sport hunting activity, including low-flying aircraft, hunting camps, and landings.

(Halas 2015)

More than half of the hunters who responded to Fix and Ackerman’s (2015) Sport Hunter Survey, said they did not receive information regarding subsistence areas to avoid or local hunting traditions to follow. When this information was received, the NPS was rarely the source (Fix and Ackerman 2015). Private allotments along the Noatak River, as well as favored and traditional camping spots are immensely important to local hunters for successful harvests.

In 2022, the preserve was closed to non-resident sport hunters via a 2-year special action aimed at addressing user conflict. During the closure, non-resident hunters were transported to the open lands north of the closure, in the same Game Management Unit (GMU 23). In 2023 public meetings to discuss full closure of federal lands to non-resident sport hunting, there was growing concern from communities regarding this hunter displacement. During the fall caribou migration, caribou travel from north to south. This movement makes them accessible to local Nuatakmiit hunters. However, in the past 6 years, caribou have delayed or abbreviated their southward migration and stayed north longer or throughout the winter (Pers. comm. with caribou and local biologists Kyle Joly, Raime Fronstin, and Alex Hansen). This change has been detrimental to communities that rely on the herd for subsistence, and there have been several years in which villages have not had access to caribou. Subsistence users worry that the sport hunters positioned in the north may compound the effects that warmer weather is already having on the migration, inhibiting southward migration further (NPS CAKR SRC 2023, 2024; NPS KOVA SRC 2023).

Current Status

Wildlife management in Alaska is regulated by the Federal Subsistence Board | U.S. Department of the Interior (FSB) and the Board of Game Home, Alaska Department of Fish and Game (BOG). The FSB manages subsistence hunting and fishing on federal public lands in Alaska, prioritizing rural Alaskans’ subsistence needs under ANILCA. The BOG oversees hunting regulations on state lands and waters, focusing on managing wildlife populations for both subsistence and recreational uses under state law. Both Boards have advisory councils that represent different regions in Alaska. These councils provide recommendations to the Boards, develop proposals to change regulations, review proposals submitted by the public, and provide an open forum for public concerns regarding wildlife and harvest matters.Today the WACH is in a 20+ year decline, with a 2023 population estimate of 152,000 animals from its peak in 2003 at 490,00 animals (WACH Management Plan 2019: 2). Due to this decline, both the FSB and the BOG and approved (with modifications) caribou regulatory proposals submitted by concerned local advisory committees to reduce subsistence bag limits from five caribou per day to fifteen caribou per year, per hunter, in which only one can be a cow (female caribou). The Federal Subsistence Board, using the WACH Working Group Cooperative Management Plan as a guide, approved the closing of all federal land in GMU 23, including Noatak National Preserve, to non-federally qualified subsistence users (non-resident sport hunters) until the herd reaches 200,000 animals (Federal Subsistence Board Closes Federal Public Lands to Caribou Hunting by all Users in Units 11, 12 remainder, and 13 for 2024-2025 | U.S. Department of the Interior (doi.gov)). The Board of Game, on the other hand, did not approve closure of state lands to non-residents, instead changing the hunt in GMU 23 from an unlimited registration hunt to a drawing hunt with up to 300 permits—which is more than the average annual number of hunters, effectively increasing the number of harvests. While local biologists agree that 300 caribou is not a biologically significant detriment to the herd, many locals argue that 300 caribou is enough to feed an entire village and is therefore significant to the people who depend upon them (NWARAC 2023, Kotzebue AC 2024). The average number of residents in a village in Northwest Alaska is 398. The significance of a harvested caribou has very different meanings to biologists, land managers, non-resident sport hunters, and local and Iñupiaq subsistence hunters.There have been attempts to reconcile the different perspectives. In 2017, the Caribou Hunter Success Working Group was formed by Kotzebue state and federal agencies, NANA Regional Corporation, Maniilaq Association, and the Northwest Arctic Borough in response to a motion by the Cape Krusenstern Subsistence Resource Commission to address a need for hunter education (Atkinson 2020). The Kiana Elders Council and Native Village of Kotzebue both worked with this group to create hunter ethics posters. Despite these efforts, concerns by subsistence users remain largely unchanged as of 2024. Continued requests for outreach have been called for (NWARAC 2023: 97):

[In reference to non-resident hunters] Educate the outside users that there are villages out there, down there, and let them know that our cost of fuel is high and other people have no means to go out and hunt.

Conclusion

Preserving and protecting cultural and natural resources for the enjoyment of future generations is the mission of the NPS. “Hunter success,” “love for children,” and “respect for nature,” are 3 of the 18 values in the Inupiat Ilitqusiat. These values are not so different from the NPS mission. This article attempts to illustrate the challenges that local Nautakmiit hunters face when outside hunters with different means of access and different hunting ethics come to their homeland. These are the challenges the NPS faces as well when attempting to manage resources for both hunting groups. The studies referenced in this article should continue to be referred to by management bodies as they make decisions for the protection of the caribou and the right to subsist. The complexity of these issues, diversity of people affected, and importance of food security warrant further investment. The NPS will continue to prioritize documenting these world views and seeking solutions to apply in management decisions.References

ANILCA. 96th Congress. 1980.Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, Title 8. Public Law 96-487. December 2, 1980. https://www.nps.gov/locations/alaska/upload/ANILCA-Electronic-Version.PDF

Atkinson, H. 2020.

Mobilizing Indigenous Knowledge through the Caribou Hunter Success Working Group. Land 9(11): 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110423

Burch, E. S., Jr., E. Jones, H. P. Loon, and L. D. Kaplan. 1999.

The Ethnogenesis of the Kuuvaum Kanjiagmuit. Ethnohistory 46(2): 291-327. http://www.jstor.org/stable/482963

Calef, G. W., E. A. DeBock, and G. M. Lortie. 1976.

The reaction of barren-ground caribou to aircraft. Arctic 29: 201-212. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic2805

Deur, D., H. Atkinson, and J. Hebert. 2021.

Noatak National Preserve Traditional Use Study: A Phase 1 Review of Existing Literatures Relating to Traditional Noatak Caribou Hunting. Traditional Use Study. Portland State University.

Fischer, C. A., D. C. Thompson, R. L. Wooley, and P. S. Thompson. 1977.

Ecological studies of caribou on the Boothia Peninsula and in the district of Keewatin, NWT, 1976. With observations on the reaction of caribou and muskoxen to aircraft disturbance, 1974-1976. Polargas. 239 pp.

Foote, D. C. 1965.

Exploration and resource utilization in northwestern arctic Alaska before 1855. PhD Dissertation, Department of Geography, McGill University. http://digitool.library.mcgill.ca/webclient/StreamGate?folder_id=0&dvs=1542137355644~847 (accessed 13 November 2018)

Fix, P. and A. Ackerman. 2015.

Noatak National Preserve Sport Hunter Survey. Natural Resource Report NPS/NOAT/NRR—2015/1005.

Federal Subsistence Board (FSB). 2023.

Federal Subsistence Board Minutes for Wildlife Special Action WSA22-05/06. Office of Subsistence Management. National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Kotzebue, AK, USA. Wildlife Special Action WSA22-05/06 (doi.gov)

Fullman, T. J., K. Joly, and A. Ackerman. 2017.

Effects of Environmental Features and Sport Hunting on Caribou Migration in Northwestern Alaska. Mov Ecol. Mar 1;5:4. doi: 10.1186/s40462-017-0095-z. PMID: 28270913; PMCID: PMC5331706.

Georgette, S. and H. Loon. 1988.

The Noatak River: Fall Caribou Hunting and Airplane Use. Technical Report 162. Division of Subsistence Alaska Fish and Game.

Halas, G. 2015.

Caribou Migration, Subsistence Hunting, and User Group Conflicts in Northwest Alaska: A Thesis. MA, Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Harrington, F. H. and A.M. Veitch. 1992.

Calving success of woodland caribou exposed to low-level jet fighter overflights. Arctic 45: 213-218.

Jakimchuk, R. D. 1980.

Disturbance to barren-ground caribou: A review of the effects and implications of human developments and activities. In Analyses of the characteristics and behavior of barren-ground caribou in Canada, Report to Polar Gas Project by Rangifer Associates Environmental Consultants and R. D. Jakimchuk Mgmt. Associates, Sidney, B.C. 281 pp.

Kotzebue Advisory Committee (AC). 2024.

Alaska Department of Fish and Game minutes of the Kotzebue Advisory Committee meeting held on January 16, in Kotzebue, AK, USA. RC014. rc014_Kotzebue_AC_Minutes.pdf (alaska.gov)

Magdanz, J. 1979.

Subsistence Living in a Changing Eskimo Village. Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellowship. Eskimo Fish Camp - James Magdanz (aliciapatterson.org)

Maier, J. A. K. 1996.

Ecological and physiological aspects of caribou activity and responses to aircraft overflights. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Alaska, Fairbanks. 139 pp.

McCourt, K. H., J. D. Feist, D. Doll, and J. J. Russell. 1974a.

Reactions of caribou to aircraft disturbance. Pages 183–208 in K. H. McCourt, J. D Feist, D. Doll, and J. J Russell, eds. Disturbance Studies of caribou and other mammals in the Yukon and Alaska, 1972. Arctic Gas Report 5. Canadian Arctic Gas Study, Limited and Alaskan Arctic Gas Study Company. Calgary, Alberta. 246 pp.

McCourt, K. H, and L. P. Horstman. 1974.

The reaction of barren-ground caribou to aircraft. Chapter I in R. D. Jakimchuk, eds. The reaction of some mammals to aircraft and compressor station noise disturbance. Canadian Arctic Gas Study, Limited and Alaskan Arctic Gas Study. Arctic Gas Report 23:1–36.

National Park Service, Cape Krusenstern Subsistence Resource Commission (NPS CAKR SRC). 2024.

National Park Service Minutes of the Subsistence Resource Commission for Cape Krusenstern National Monument meeting held in Kotzebue, AK, USA.

National Park Service, Cape Krusenstern Subsistence Resource Commission (NPS CAKR SRC). 2023.

National Park Service Minutes of the Subsistence Resource Commission for Cape Krusenstern National Monument meeting held in Kotzebue, AK, USA.

National Park Service, Kobuk Valley Subsistence Resource Commission (NPS KOVA SRC). 2023.

National Park Service Minutes of the Subsistence Resource Commission for Kobuk Valley National Park meeting held in Kotzebue, AK, USA.

Northwest Arctic Advisory Council (NWARAC). 2023.

Official Transcript, Northwest Arctic Regional Advisory Council Public meeting held in Anchorage, AK, USA. 17-Oct-23 (doi.gov)

Shirar, S. 2009.

Subsistence and Seasonality at a Late Prehistoric House Pit in Northwest Alaska. Journal of Ecological Anthropology 13(1): 6-25. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/jea/vol13/iss1/1

Steinacher, S. 2006.

A Crisis in the Making in Northwest Alaska: Caribou, Hunting Pressure and Conflicting Values. Alaska Fish & Wildlife News. September 2006. https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=236. (Accessed June 26, 2024)

Stinchcomb, T.R., T.J. Brinkman, and S.A. Fritz. 2019.

A Review of Aircraft-Subsistence Harvester Conflict in Arctic Alaska. Arctic 72(2): 131-150. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic68228

Stinchcomb, T. R., T. J. Brinkman, and D. Betchkal. 2020.

Extensive aircraft activity impacts subsistence areas: acoustic evidence from Arctic Alaska. Environ. Res. Lett. 15(11): 115005. DOI 10.1088/1748-9326/abb7af

Surrendi, D. C., and E. A. DeBock. 1976.

The immediate behavioral response of caribou to aircraft. Chapter 3.9.4, Pages 98–188 in Seasonal distribution, population status and behavior of the Porcupine Caribou Herd. Canadian Wildlife Service, Ottawa, Quebec. 144 pp.

Uhl, B., and C. Uhl. 1979.

THE NOATAK NATIONAL PRESERVE Nuatakmitt: A Study of Subsistence Use of Renewable Resources in the Noatak River Valley. 19. University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Valkenburg, P., and J. L. Davis. 1985.

The reaction of caribou to aircraft: a comparison of two herds. Pages 7–9 in A. Martell, and D. E. Russell, eds. Proceedings of the First North American Caribou Workshop. Whitehorse, Y.T. Canadian Wildlife Service Special Publication, Ottawa.

Western Arctic Caribou Herd (WACH) Management Plan. 2019.

Western Arctic Caribou Herd Working Group Cooperative Management Plan - December 2019. 54 pp. https://westernarcticcaribou.net/